Table of Contents

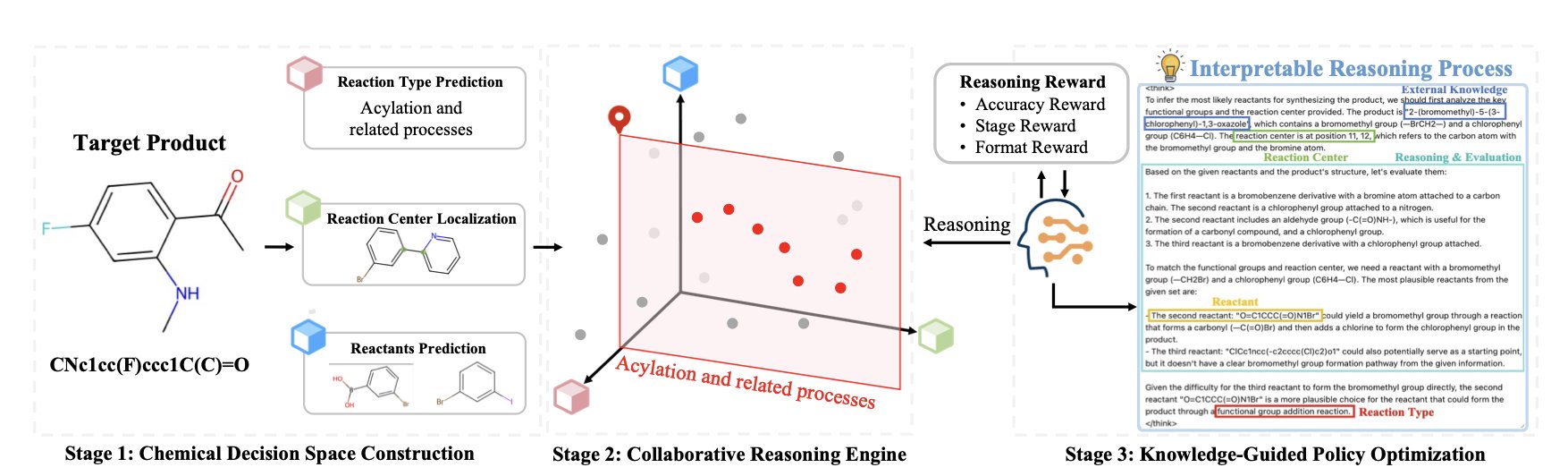

- Using reinforcement learning, Retro-Expert trains a large model in a “sandbox” of expert models to think like a chemist. It not only provides a retrosynthesis route but also explains its reasoning.

- Researchers used simulated data to “stress test” Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and found their performance depends heavily on data quality (like feature entanglement). This paper is a guide to using VAEs and avoiding common pitfalls.

- This study challenges conventional wisdom, showing that “promiscuous” molecular fragments aren’t always bad. They act like master keys that fit multiple locks, revealing hidden structural similarities between different protein targets.

1. A New Way for AI Chemists: Retro-Expert Makes Retrosynthesis Explainable

Most retrosynthesis AIs are like students who only write down the final answer on a test. You give them a molecule, they spit out a few routes. But if you ask why they chose that route, you get silence. This is a big problem for chemists in the lab. Who would risk their budget and their hair on a black box that can’t explain itself?

Retro-Expert tries to solve this trust problem.

The researchers built an “expert panel” of specialized models, each trained on specific reaction types. These experts brainstorm possible ways to break down a molecule, creating a high-quality “sandbox” of chemical decisions. Then, the main character—a Large Language Model (LLM)—steps in. Its job isn’t to start from scratch. Instead, it acts like an experienced project manager, reasoning through the options in the sandbox to find the most efficient synthesis path.

The key here is Reinforcement Learning (RL). The method is similar to training a Go-playing AI. It doesn’t learn by memorizing moves but by playing countless games and figuring out winning strategies on its own. The LLM in Retro-Expert does the same thing. It constantly tries different paths in the chemical decision space. If a chosen path leads to an accurate and logical solution, it gets a reward. Over time, it learns to think like a chemist, understanding which reactions are reliable in certain contexts and which functional groups will “fight” with each other.

The benefits are immediate. First, the model finally explains itself. It doesn’t just give you a cold list of reactants. It provides an explanation based on chemical principles, like: “I chose to break the bond here because this is a classic Wittig reaction, the starting materials are easy to buy, and the reaction conditions are mild.” This kind of transparency is the foundation for building trust between chemists and AI.

Second, the framework is flexible. Chemical knowledge is always evolving, with new reactions appearing all the time. Retro-Expert’s modular design means you can just plug in a better “expert model” to upgrade the system without starting over. In the fast-paced world of drug discovery, this is a huge engineering advantage.

Of course, performing well on a computer isn’t enough. The researchers put on their lab coats and validated the model with wet-lab experiments. They successfully synthesized a molecule that had never been reported in the literature and also found a completely new synthesis route for a known molecule.

📜Paper Title: Retro-Expert: Collaborative Reasoning for Interpretable Retrosynthesis 📜Paper URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.10967v1

2. Integrating Multi-Omics with VAEs: Read This “Pitfall Guide” Before You Start

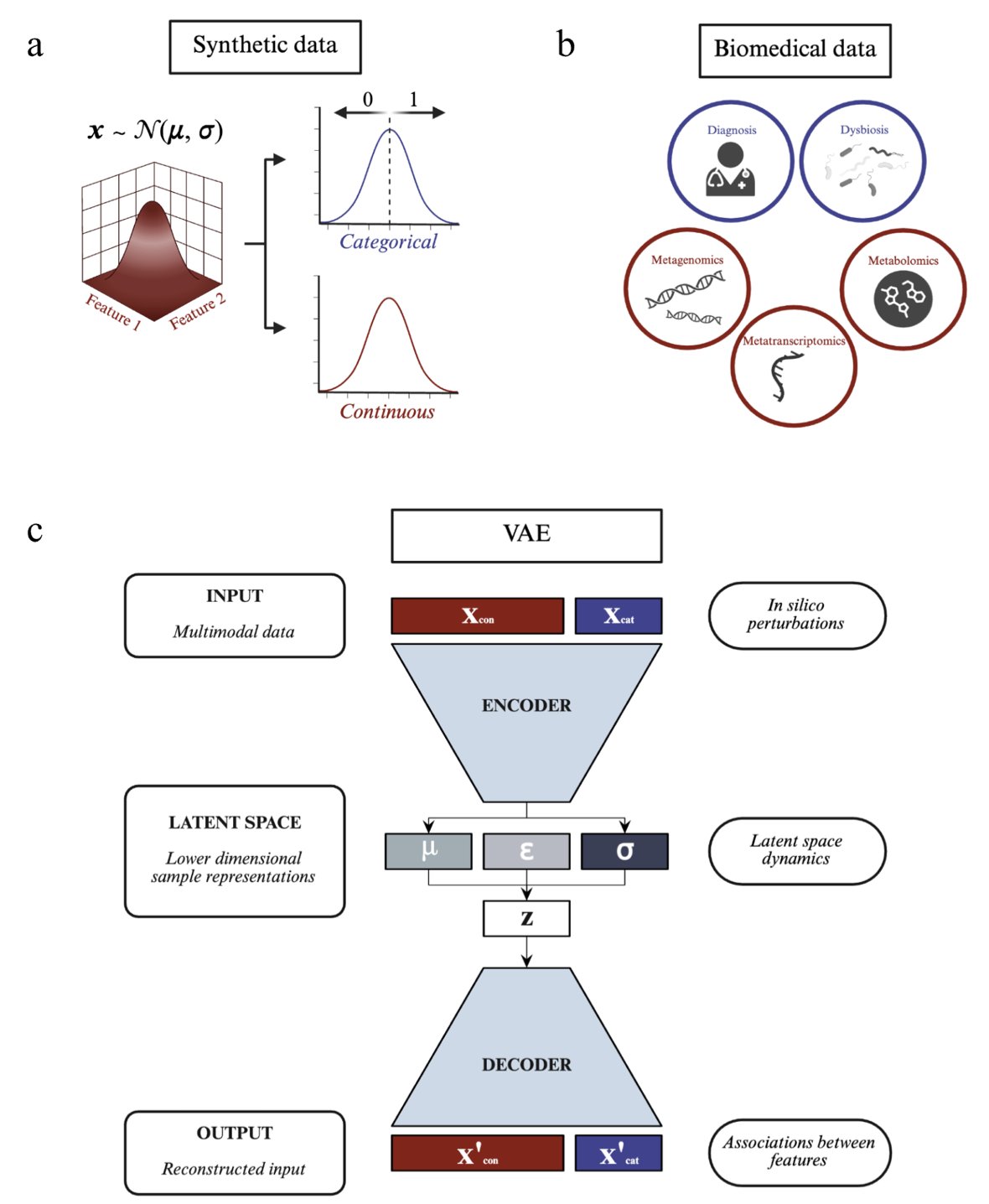

In biomedical research today, everyone seems to have “omics” data. Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics… the data dimensions just keep growing. Figuring out how to integrate all this varied data to uncover useful biological patterns is one of the biggest challenges in computational biology.

The Variational Autoencoder (VAE) is one of the tools for this job. You can think of it as a powerful data compressor. It takes high-dimensional, complex multi-omics data and squeezes it into a more fundamental, low-dimensional “latent space.” In theory, relationships between samples become clear in this space. We can even run in silico perturbations—for example, simulating an increase in a gene’s expression to see which metabolites react.

It sounds great. But in practice, we often use VAEs as black boxes. The model runs, it gives you a result, but is the result reliable? Is the model’s performance due to the algorithm or the data? Nobody is really sure.

This paper opens a crack in that black box to let us see what’s going on inside.

Using Synthetic Data to Establish a “Ground Truth”

The researchers didn’t start with complex real-world biological data, because in real data, we never know the “ground truth.”

So, they created a series of synthetic datasets themselves. In these datasets, the relationships between variables were predefined by them, creating a known “ground truth.” It’s like a teacher solving the test before giving it to the students.

They then used this synthetic data to systematically test a multi-modal VAE model.

Key Practical Takeaways

Through this rigorous benchmarking, the researchers arrived at several useful conclusions: 1. Data quality is everything. A model’s ability to reconstruct data is highly correlated with the data’s own properties, like feature entanglement and the sample-to-feature ratio. Spending time understanding and preprocessing your data is more effective than tweaking model parameters. 2. Use in silico perturbations with care. They extended the method for in silico perturbations from handling discrete variables, like gene knockouts, to continuous variables, like changes in protein or metabolite concentrations. This is a better match for real biological scenarios. 3. We need more robust evaluation methods. They found that traditional statistical tests are prone to false positives when evaluating the effects of in silico perturbations. So, they proposed a new, more reliable quantitative method.

Finally, they applied what they learned from the synthetic data to a real multi-omics dataset from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), showing the framework’s potential for solving real-world problems.

This work is like a detailed user manual or lab report. The VAE is a great tool, but it’s best to understand its quirks before you use it.

📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.08.18.670835 💻Code: https://github.com/Simon-Rasmussen-Lab/MOVE

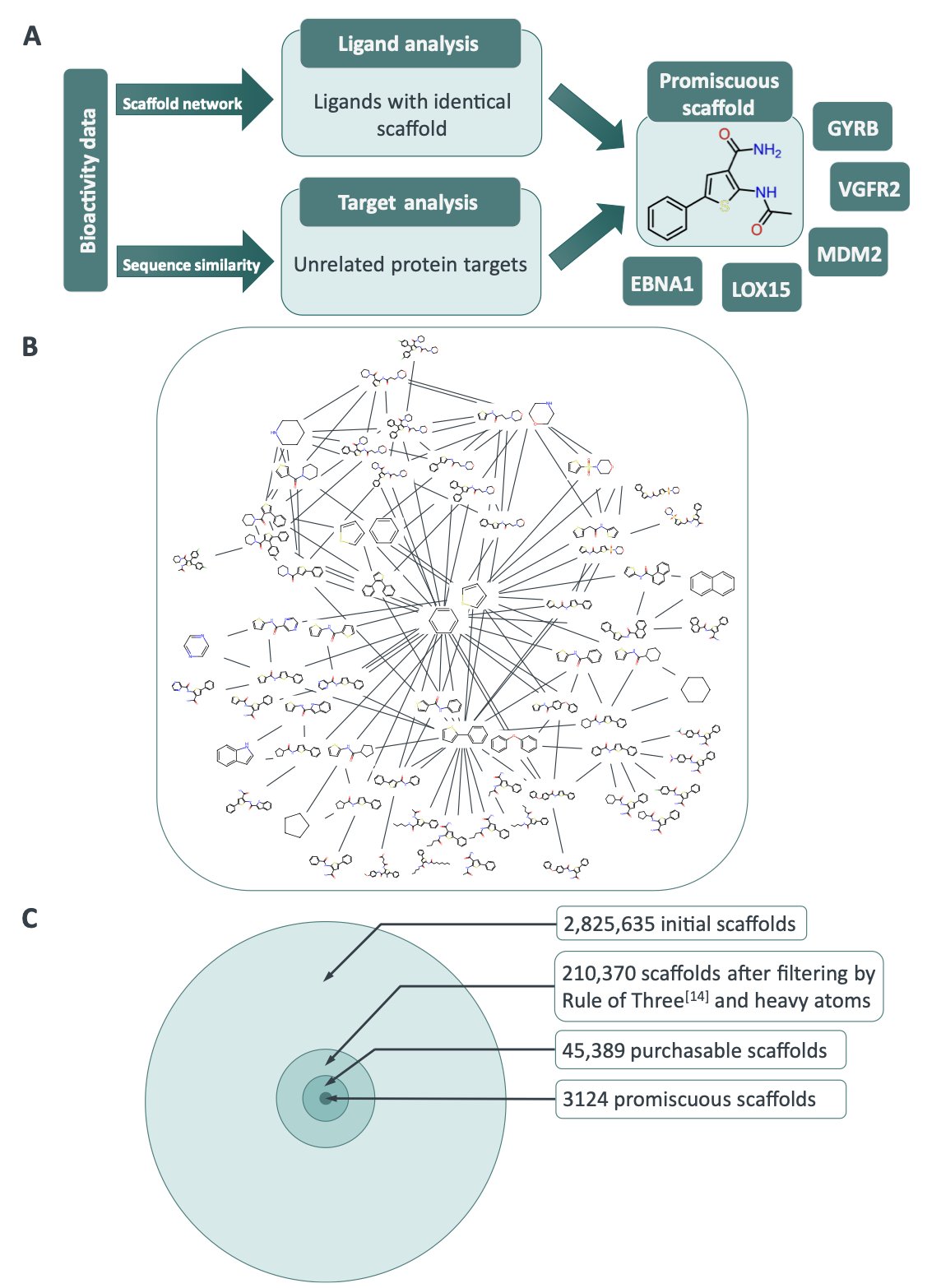

3. The “Promiscuous” Molecule: A Bug or a Feature in Drug Design?

In drug discovery, the word “promiscuous” is enough to make a project lead’s blood pressure spike. Along with “toxic” and “insoluble,” it’s always in the top three on the list of “words I never want to hear about my lead compound.” A promiscuous molecule is like a social butterfly inside a cell, binding to a bunch of targets it shouldn’t. This usually leads to off-target effects, toxicity, and a failed project.

So, we have always tried to avoid these molecules.

But this preprint on ChemRxiv asks a counterintuitive question: Before we throw these “butterflies” in the trash, should we listen to what they have to say?

The authors started by systematically identifying 3,124 chemical scaffolds with a “promiscuous” history from the large ChEMBL database. They then took a closer look at one of them: a phenyl-thiophene scaffold. It can bind to five completely different proteins.

Through docking simulations, they discovered that these five unrelated proteins all share a similar hydrophobic subpocket.

This promiscuous fragment is like a master key that can open five different locks on five different doors. It works because even though the locks look and function differently, their internal “tumbler” structures are surprisingly similar. The fragment had unintentionally discovered a common vulnerability in the protein world.

This changed the story from bad news to good news.

If this is a common vulnerability, can we take this master key and actively look for other doors with similar “tumblers”?

That’s exactly what they did. The researchers used the phenyl-thiophene structure to screen the entire Protein Data Bank (PDB), looking for other proteins with a similar subpocket. They found an unexpected new target: Cruzipain, a protease from the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi.

At this point, it was a good computational chemistry story. But they went back to the lab to verify the prediction in a test tube. The results confirmed that the fragment does indeed inhibit Cruzipain’s activity.

This provides a whole new hunting strategy for researchers in Fragment-Based Drug Design (FBDD). In the past, we would first identify a target, then go to our fragment library to find a “bullet” that could hit it. Now, we can work backwards. We can start with the most promiscuous “bullets”—the ones with the highest hit rates—and see which different targets they can hit. This is a new way to explore biological space starting from chemical space.

But there’s more. The most elegant part of this strategy is the final step. Once you understand why your fragment is promiscuous (because it perfectly fits that common “tumbler”), you can consciously design the “arms” and “legs” you add to grow it into a full drug molecule. You can make these additions interact with the unique regions of your desired target.

You use its promiscuity to get your foot in the door, then use rational design to give it specificity, ensuring it stays in the right room.

So, is promiscuity a bug or a feature? It depends on what you want from it. What do you think?

📜Title: Promiscuous scaffolds: Friend or foe in fragment-based drug design? 📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-bmv1h