Table of Contents

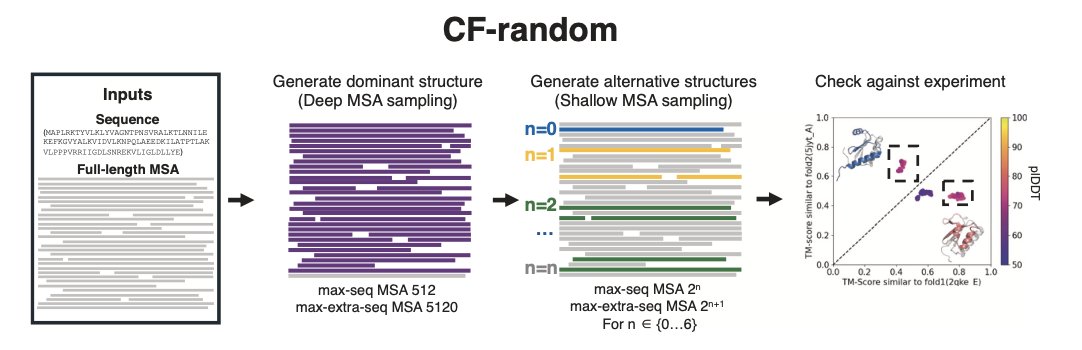

- A new method, CF-random, cleverly “starves” AlphaFold2’s input to reveal the hidden, multiple conformations of proteins, suggesting the protein world is far more dynamic than we thought.

- By “borrowing” models trained on big data, researchers efficiently screened for potential new antibiotics for a specific bacterial strain with limited data, offering a new way to tackle the stubborn problem of drug resistance.

- The HypSeek model learns protein-ligand interactions in hyperbolic space, using its geometric properties to effectively solve the “activity cliff” problem in virtual screening.

2. AI vs. Superbugs: Can New Antibiotics Be Found with Little Data?

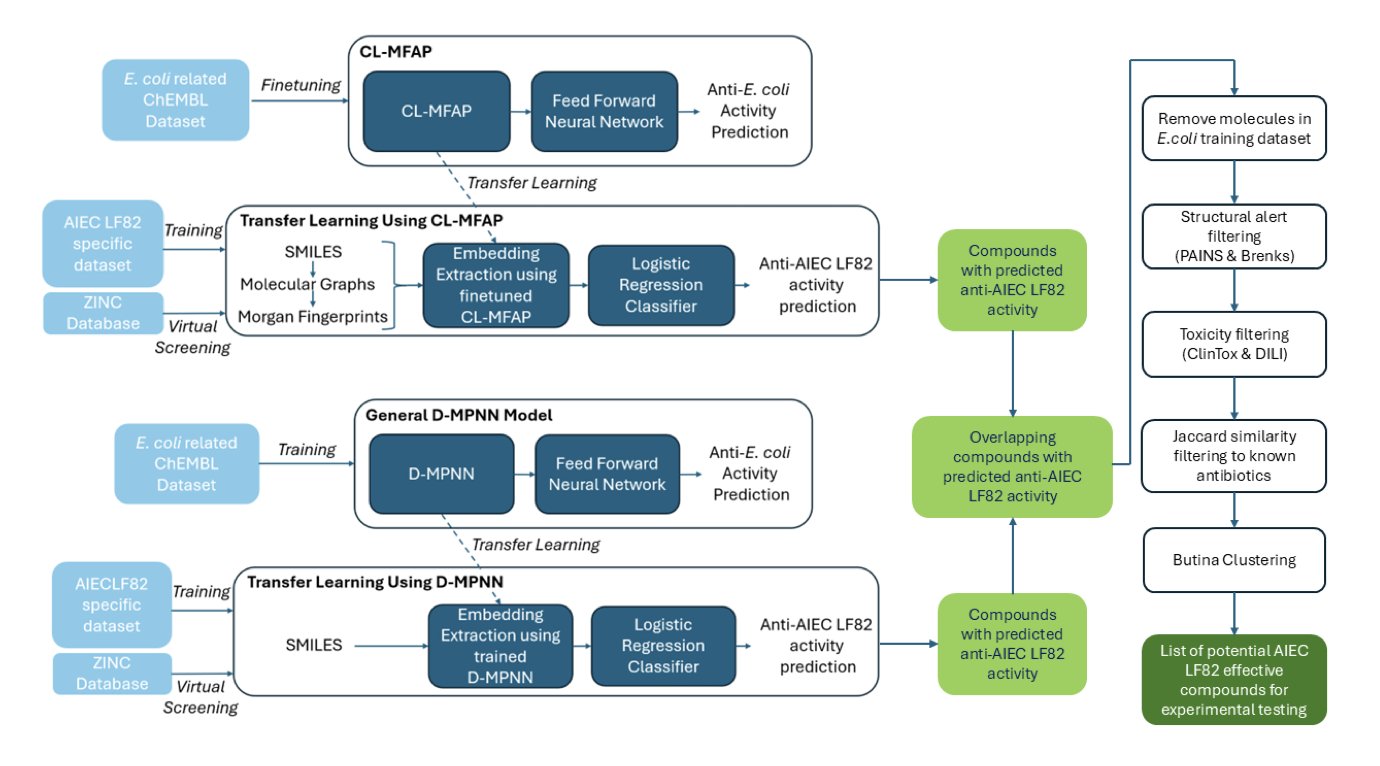

Most of the time, AI models are like hungry beasts that you have to feed massive amounts of data to get anything useful back. But what if you’re targeting a less common but equally deadly bacterium, like the AIEC LF82 strain that contributes to Crohn’s disease? Where do you get enough data?

The answer: transfer learning.

You wouldn’t send a medical student straight into surgery; you’d have them learn basic anatomy first. Similarly, researchers first trained their deep learning models—a base model called CL-MFAP and a Graph Neural Network (GNN) called D-MPNN—on a large, general database of antimicrobial activity. This turned the models into “generalists” with a basic understanding of what an “antibiotic-like molecule” looks like.

Then, they used their small, specialized dataset for AIEC LF82 to “fine-tune” and “calibrate” the models. This process turned the “generalists” into “specialists” focused on AIEC LF82.

How did this one-two punch perform? They used this system to screen nearly 11 million commercially available compounds. This wasn’t just a simple scoring exercise. A true expert would appreciate the thoroughness of their screening process.

First, they used the CL-MFAP model, which is multi-modal. This means the model doesn’t just look at one aspect of a molecule. It considers SMILES strings, Morgan fingerprints, and molecular graphs all at once to get a 360-degree understanding. This is like a seasoned chemist examining a molecule from different angles.

Next came the tough filtering stage.

Finally, using Butina clustering, they selected the 100 most structurally diverse candidates from the survivors. The results showed that these 100 molecules belonged to 82 different Bemis-Murcko scaffolds.

Of course, all of this is still in the computer. These 100 molecules now have to be tested in a wet lab. MIC experiments, kill curves, animal models… the real challenge is just beginning.

📜Paper: https://openreview.net/forum?id=QI0Wx8LY8D

3. Drug Discovery in Hyperbolic Space: An AI That Understands “Activity Cliffs”

In drug discovery, especially during lead optimization, one of the most frustrating problems is the “activity cliff.”

What does that mean?

It’s when you work hard to make a tiny change to a molecule—say, swapping a methyl group for an ethyl group—only to find the new molecule’s activity doesn’t just increase or decrease slightly, but plummets by a factor of a thousand. This phenomenon is a huge headache for predicting structure-activity relationships (SAR).

Traditional machine learning models, especially those that operate in Euclidean space (the three-dimensional space we’re familiar with), often fail here. In their view, two structurally similar molecules should be close together and have similar properties. They struggle to understand how a tiny change can lead to a massive difference.

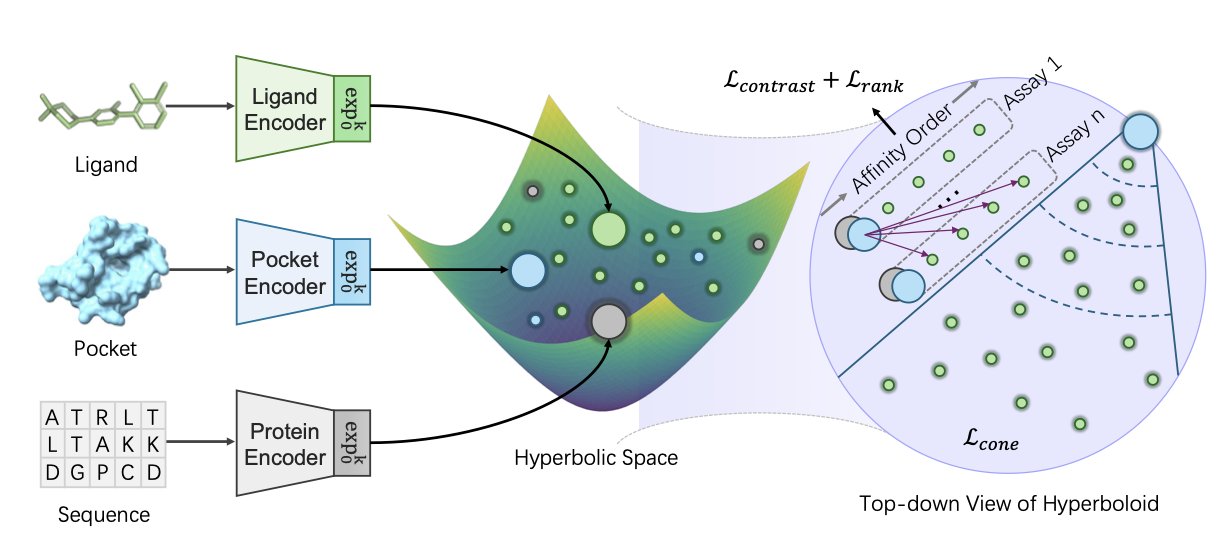

The HypSeek model from this paper offers a new perspective to solve this problem.

Upgrading the Toolkit: From Euclidean to Hyperbolic Space

The authors argue that the problem isn’t the model, but the “space” we use to represent molecules. They boldly embedded molecules, protein pockets, and sequences into a non-Euclidean geometric space called “hyperbolic space.”

What’s so special about hyperbolic space?

You can think of it as a bowl whose edges stretch out to infinity. In this space, distance is calculated differently than we’re used to.

What does this mean? Two points that are structurally very similar (like that activity cliff pair) can be placed very far apart in hyperbolic space. This space naturally has the ability to “magnify” small differences.

This gives the model a powerful “inductive bias.” The model no longer needs to struggle to learn how to distinguish activity cliffs; the geometry of hyperbolic space itself does most of the work.

How Does It Perform? Let’s See the Results

HypSeek showed significant improvements across several benchmarks: 1. Virtual Screening: On the classic DUD-E dataset, the early enrichment factor increased from 42.63% to 51.44%. This means a higher probability of finding true active molecules among the top-ranked screening hits. 2. Affinity Ranking: In an affinity ranking task, the correlation coefficient improved from 0.5774 to 0.7239. This shows it predicts changes in affinity more accurately. 3. Confronting Activity Cliffs: When tested specifically on activity cliff pairs, the score difference produced by HypSeek was an order of magnitude larger than that of Euclidean-based models. This proves it can more clearly separate the “good” molecules from the “bad” ones.

The paper notes that in cases where even computationally expensive Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) methods predicted the wrong direction of affinity change, HypSeek’s hyperbolic scores still provided the correct ranking consistent with experimental results.

Sometimes, solving a hard problem doesn’t require a more complex model, but a more suitable mathematical framework. Introducing hyperbolic geometry to drug discovery opens a new door for understanding and predicting complex protein-ligand interactions.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.15480