Table of Contents

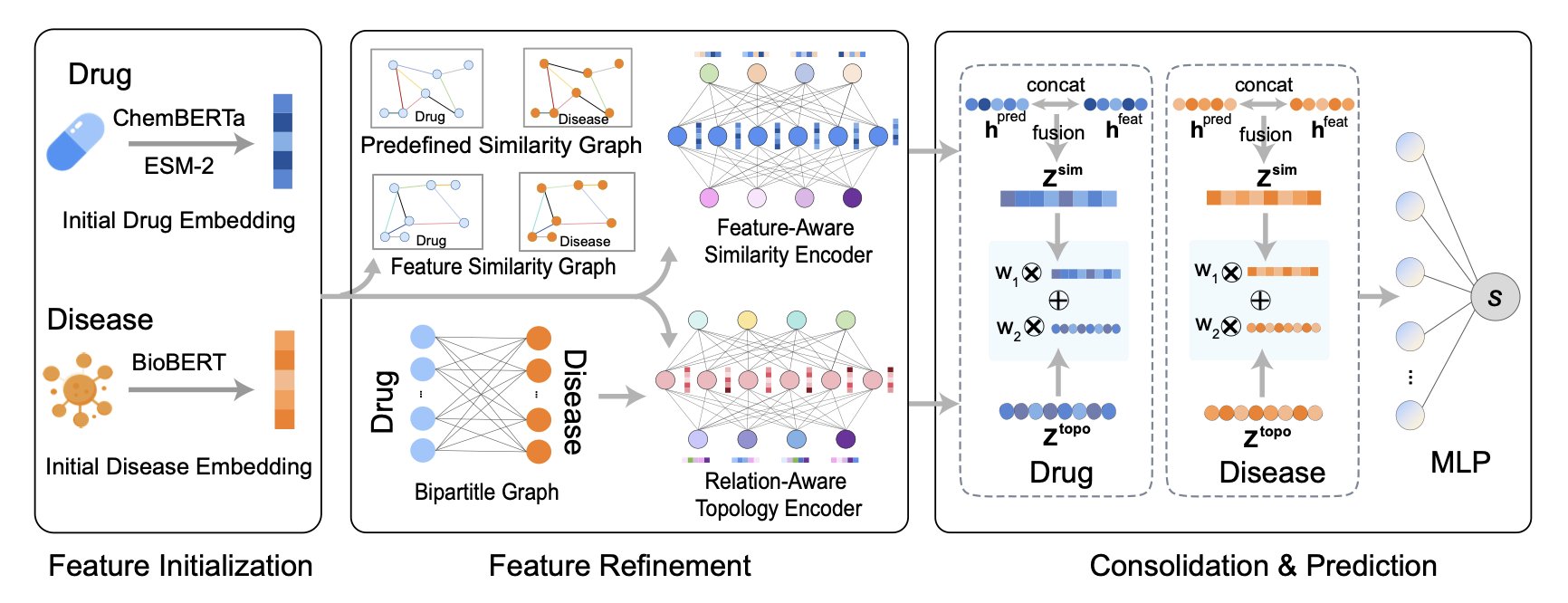

- DREAM-GNN uses a dual-channel architecture to analyze both the known drug-disease network and their intrinsic features, greatly improving the accuracy of drug repurposing predictions.

- DecoyDB created a massive dataset of millions of “wrong answers,” allowing AI to learn the “right way” for molecules to bind through contrastive learning. This has significantly boosted the accuracy of affinity prediction.

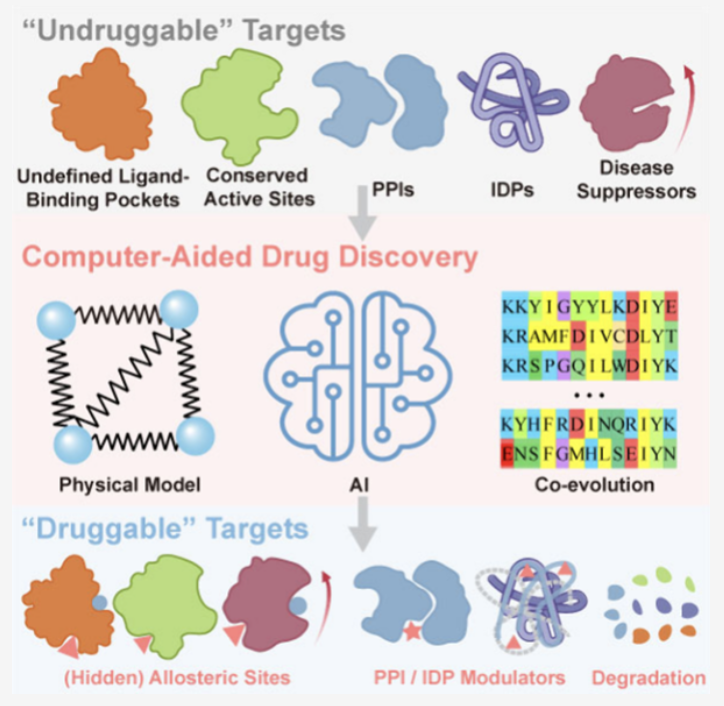

- Computational methods and AI are bringing new weapons to bear on targets once deemed “undruggable.” From allosteric modulation to protein degradation, the rules have changed.

1. DREAM-GNN: A Two-Lane Highway for Drug Repurposing

Drug repurposing sounds like an alchemist’s dream: take an old drug, one we already know is safe, and use it to treat a new disease. It saves money, it saves time. It’s perfect.

But in practice, it’s like finding a needle in a haystack. People have been talking about computational methods for years, but many models are either too simple or too specialized.

Some models only look at the network of relationships. For example, if drug A treats disease X, and drug B treats disease Y, maybe drug C, which is structurally similar to A, can also treat X. Other models only look at features. If drug D and drug E both inhibit a certain kinase, they might treat the same type of cancer. Both approaches make sense, but each only sees half the picture.

DREAM-GNN’s approach is direct: why choose when you can have both?

It was designed with a dual-channel architecture, which is a brilliant move.

The first channel is a relationship expert. It builds a huge graph of all known drug-disease associations and specializes in learning the patterns within this network’s topology. It’s like a social network analyst, studying “who is connected to whom.”

The second channel is a feature expert. It ignores known treatment relationships and instead dives deep into the intrinsic properties of the drugs and diseases. How does it do this? It doesn’t start from scratch. It brings in outside help: ChemBERTa to understand the chemical language of small molecules, ESM-2 to grasp the biological function of protein targets, and BioBERT to parse medical text descriptions of diseases. These are all pre-trained models with extensive experience in their fields. DREAM-GNN integrates insights from these experts to determine which drugs “look alike” and which diseases have “similar pathologies.”

Finally, the information from these two highways merges at an intersection. The model combines intelligence from both the “relationship network” and “similarity features,” making its predictions far more reliable than those from single-focus models.

The data backs this up. DREAM-GNN performs at the top on multiple standard datasets. And it particularly excels on the AUPRC metric. This metric is crucial for real-world applications because it shows how well the model can find the few true positive pairs in a highly imbalanced dataset where most drug-disease pairs are unrelated.

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.07.663530v1

2. DecoyDB: Giving AI a High-Quality “Wrong-Answer” Key

In the world of computational drug discovery, predicting the binding affinity between a small molecule and a protein is a constant headache.

We have all sorts of fancy Graph Neural Network (GNN) models, but most of them are underfed. High-quality, labeled training data is just too scarce. It’s like trying to train a world-class art connoisseur by showing them only three paintings.

Contrastive Learning is a popular solution. Instead of telling the model the “right answer,” you show it a pair of things and ask it to judge if they are “alike.” For molecular binding, this means teaching the model to distinguish between “good” and “bad” binding poses.

But here’s the problem: we have examples of “good” poses (from crystal structures), but where do we find enough “bad” ones for comparison?

The old way was crude: take the correct structure and just randomly shake or twist it to create a “fake” one.

The issue with this method is that many of the poses you create are biochemically nonsensical, with impossibly high energy. Training a model with this kind of “junk” negative data is like teaching a child to recognize a cat by showing them a picture of a cat and a picture of a shattered mosaic. The child learns to recognize mosaics, not cats.

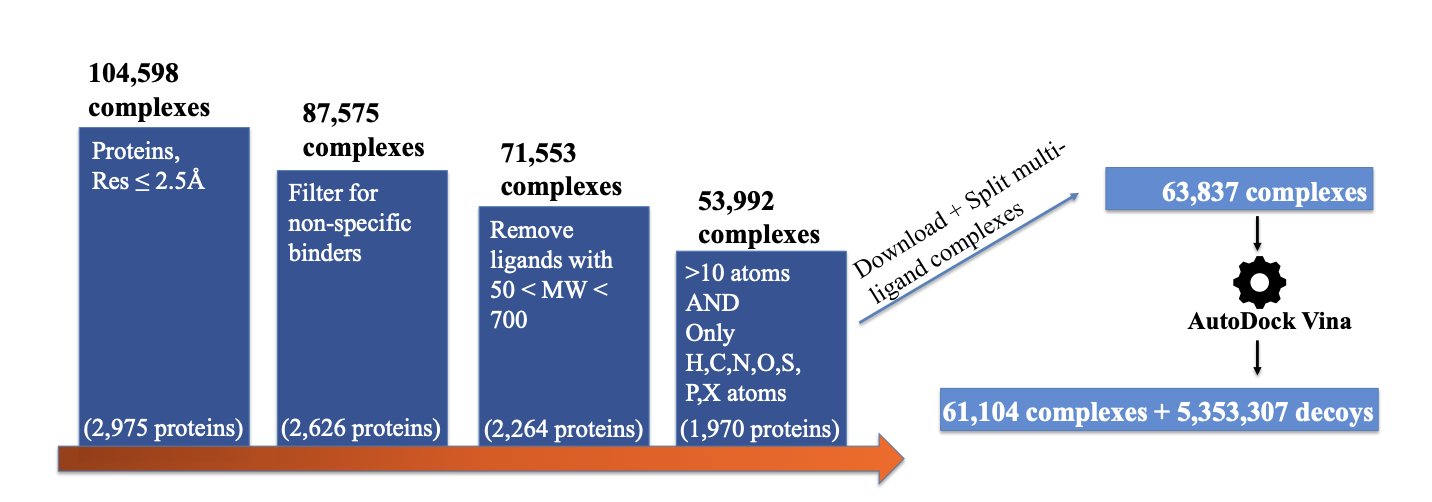

DecoyDB tries to solve this.

The creators used computational methods to generate over 5 million “decoy” structures. These decoys are all suboptimal binding poses that look plausible but are incorrect. It’s like teaching a kid to recognize a cat not by showing them a mosaic, but by showing them dogs, tigers, and foxes. These are much more sophisticated and meaningful “wrong answers.”

They also gave each “wrong answer” a label: its RMSD, which is the degree of deviation from the true structure. This doesn’t just tell the model “this is wrong,” but “this is very wrong, while that one is only slightly off.” This elevates the information content of the training data by orders of magnitude. A simple true-or-false question becomes a rich, informative Q&A session.

Good data isn’t enough; you also need good teaching methods. The researchers developed a new contrastive learning framework to go with the data. It has a dual-track loss function that enables the model to make high-level judgments between “right” and “wrong,” and also to make fine-grained distinctions between “wrong” and “more wrong.” They also added a physics-based constraint (denoising score matching). This is like having a physics teacher standing by, constantly reminding the model: “Your answer not only needs to look good, but it also has to obey the principle of minimum energy. It must be stable!”

What were the results?

Models pre-trained with DecoyDB outperformed previous models across the board in affinity prediction tasks—in accuracy, generalization, and data efficiency.

DecoyDB provides the entire field with valuable infrastructure: a high-quality, open-source “wrong-answer” key. With it, we can finally train AI connoisseurs that truly understand the art of molecular binding, not just experts at spotting flaws.

📜Title: DecoyDB: A Dataset for Graph Contrastive Learning in Protein-Ligand Binding Affinity Prediction 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.06366 💻Code: https://github.com/spatialdatasciencegroup/DecoyDB

3. AI Is Erasing the Word “Undruggable”

The word “undruggable” is like a death sentence. Once a protein target, however closely linked to a disease, gets this label, it’s basically sent to a graveyard of abandoned projects.

Why?

Because these targets either lack a well-defined pocket for a small molecule to bind to, are shapeless like a bowl of overcooked spaghetti (intrinsically disordered proteins, or IDPs), or their binding surface with other proteins is large and flat, like a wall, giving small molecules no place to grip (protein-protein interactions, or PPIs).

For decades, we could only watch as targets like c-Myc wreaked havoc in diseases, powerless to stop them.

But this review article tells us that times have changed. Computational biology and AI are tearing up that death sentence, one target at a time.

First, we’ve changed our strategy.

For IDPs that are like spaghetti, we used to think they were impossible because they lacked a stable “keyhole.” Now, computational methods like ensemble-based screening don’t try to capture a single static shape. Instead, they aim to understand the protein’s entire “dance,” finding moments of vulnerability in its dynamic movements. The fact that inhibitors for c-Myc (like Omomyc) have entered clinical trials is proof of this.

For PPI interfaces that are like walls, we no longer dream of blocking the entire surface with a single small pebble. Computational tools help us perform “geological surveys” on these walls to find tiny, often overlooked “cracks” or “hotspots,” then design molecules that can wedge precisely into them.

Second, we’ve developed new weapons.

If the front door (the active site) is blocked, we find a back door. This is the idea behind allosteric modulation. Computational simulations can help us predict “circuit switches” on a protein, far from the active site, that can remotely control its function. We find one, then flip it with a small molecule to achieve a powerful effect.

And what if there’s no back door? Then we use the most direct approach: targeted protein degradation (TPD). PROTACs and molecular glues are examples of these weapons. Instead of trying to “inhibit” the bad protein, we just get rid of it. We design a two-headed molecule: one end grabs the target protein, and the other end grabs the cell’s E3 ligase, which is responsible for trash disposal. The molecule acts like a pair of “molecular handcuffs,” linking the two. Then the cell’s own “incinerator” completely clears the target out. Computational simulation plays a critical role here, helping design the length, angle, and chemical properties of these molecular handcuffs.

This review makes it clear: we are at a paradigm shift. The word “undruggable” is slowly becoming a historical term. It didn’t reflect a property of the targets themselves, but the limitations of our past toolkits. Now, with new tools like computational methods and AI, the long list of “undruggable” targets is becoming a list of “yet-to-be-drugged” opportunities.

📜Paper: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chemrev.4c00969