Table of Contents

- By giving AI eyes to see a molecule’s overall “topological shape,” PACTNET significantly improves the accuracy of graph neural networks in predicting molecular properties, fixing their long-standing problem of “missing the forest for the trees.”

- The Seekrflow platform seamlessly integrates machine learning force fields with enhanced sampling methods to achieve end-to-end, automated, high-throughput prediction of drug-target binding kinetics and thermodynamics.

- By creating a “corporate” AI architecture, H-MoE intelligently assigns different molecules to their own “expert departments” for processing. This solves the problem of representing the diversity of vast chemical space in a way that is closer to a human chemist’s intuition.

1. AI Molecular Models Learn to See Topology

For years, people trying to teach computers chemistry have been wrestling with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

GNNs have learned to see a molecule’s “connectivity graph” like a chemist does. It knows this carbon is connected to three hydrogens and a nitrogen, and that nitrogen is connected to a carbonyl. It has gotten pretty good at understanding these local, atom-level “neighborhoods.”

But it’s always had a blind spot. It’s like a person who can only look down and trace a city map with their finger, inch by inch. They can tell you with perfect accuracy that Street A and Street B intersect at Point C. But they know nothing about the city’s overall “topography.” They don’t know if the city is built on a flat plain or a steep mountain. They don’t know if there’s a lake or a tunnel running through the city.

We know that a molecule’s properties don’t just depend on its local chemical bonds. Its overall shape, its flexibility, whether it has internal “cavities”—these global features, which we call “topology,” are just as critical.

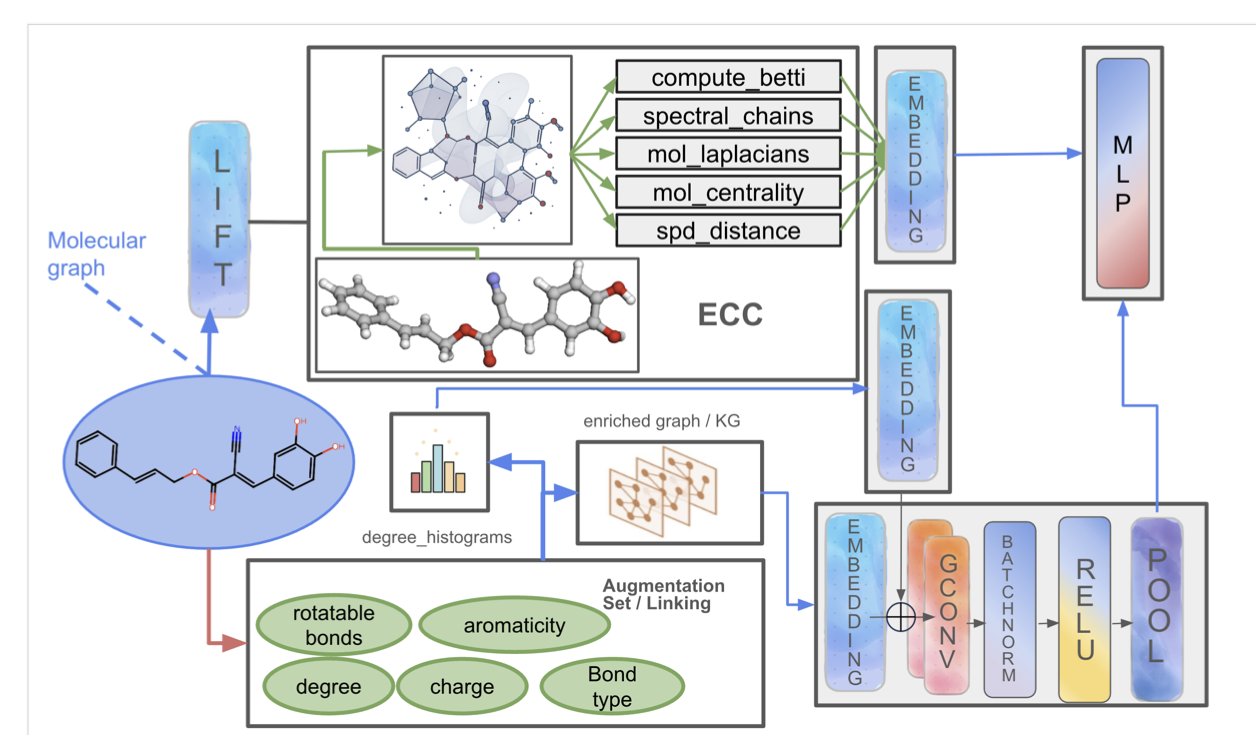

PACTNET takes a pragmatic, “hybrid” approach.

At its core is an algorithm called Efficient Cellular Compression (ECC). Before the GNN starts its traditional “connect-the-dots” work, ECC first examines the molecule’s 3D structure like a topologist. Then, it “compresses” all the complex, high-order geometric information about “holes,” “tunnels,” and “cavities” into a very compact “mathematical fingerprint” that the GNN can understand.

It’s like giving that person tracing the map a highly condensed “topographical summary” beforehand. This summary might have just a few key pieces of information: “There’s a mountain on the west side,” “There’s a lake in the city center.”

So when the GNN analyzes the intersection of Street A and Street B, it’s no longer just an isolated, 2D intersection in its mind. It also has the global “context” from the topographical summary. It will know: “Oh, this intersection is on a hillside.”

This seemingly simple, extra dimension of information yields huge returns.

In multiple standard molecular property prediction tasks, PACTNET, with its new “topographical vision,” outperformed traditional GNN architectures that were still fumbling around in the dark. It’s not only more accurate, but thanks to the compression algorithm, it’s also highly parameter-efficient. It didn’t turn into a computationally expensive behemoth.

The value of PACTNET is that it shows us a new path. It’s a way to “translate” our valuable, intuitive human understanding of 3D shapes into a language that AI can understand—in a way that is both computationally efficient and mathematically rigorous.

📜Title: Topological Feature Compression for Molecular Graph Neural Networks 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.07807v1

2. Seekrflow: AI Force Fields Unlock Prediction of Drug Binding Kinetics

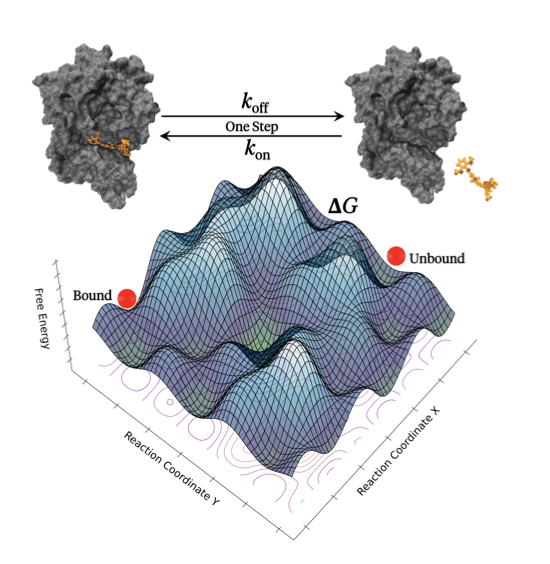

In drug discovery, we’re always chasing two goals: binding affinity (thermodynamics) and binding kinetics.

For calculating affinity, like ΔG, we have relatively mature tools like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP). They are computationally expensive, but the results are reasonably reliable. But when it comes to kinetics, especially the dissociation rate constant k_off, things get tricky. The drug’s residence time, determined by k_off, is often a better predictor of in-vivo efficacy than affinity itself. But trying to simulate a dissociation process that could last for hours is almost impossible.

Seekrflow cleverly packages two of the hottest technologies today—machine-learned force fields (ML-FF) and enhanced sampling workflows—and it does so automatically.

Let’s look at its first killer feature: the machine-learned force field.

Traditional force fields, like AMBER or CHARMM, are the bedrock of molecular simulation. But they rely on a predefined set of atom types and corresponding parameters. This rulebook often struggles when faced with “unconventional” chemical structures.

The researchers behind Seekrflow use a force field based on a Graph Neural Network (GNN). The benefit here is that we no longer need to manually define atom types. Instead, the network learns the chemical environment directly from the molecule’s connectivity (the “graph”) and then predicts energies and forces. It’s an evolution from a student who memorizes facts to one who can reason from first principles. In theory, it should be much better at generalizing to the novel molecules that medicinal chemists design.

Having a more accurate force field solves the “seeing clearly” problem, but not the “running fast” problem.

Drug-protein binding or unbinding events are extremely rare on a simulation timescale. Trying to wait for one to happen with standard molecular dynamics is like waiting for a ship to come in. So, they used enhanced sampling, specifically the milestoning method.

Instead of simulating one complete journey from start to finish, you break the entire path into a series of short “milestones.” Then, you can run many parallel simulations to figure out how long it takes for the molecule to get from one milestone to the next. Finally, you piece these time segments together to get the total time. Seekrflow automates this entire tedious process of setting up milestones, launching parallel simulations, collecting data, and analyzing the results.

The researchers applied it to several well-known systems, including inhibitors for HSP90, TTK, and trypsin. The results show that their calculated k_on and k_off values agree quite well with experimental data.

We might be one step closer to the dream of routinely predicting drug residence time during lead optimization. If this tool proves stable and efficient enough, we could get a good idea of a molecule’s kinetic properties before we even synthesize it, guiding us toward more rational molecular design.

Of course, challenges remain. How will this machine-learned force field perform on entirely new target families or more complex allosteric inhibitors? And can the actual computational cost support high-throughput screening?

📜Title: Seekrflow: Towards End-to-End Automated Simulation Pipeline with Machine-Learned Force Fields for Accelerated Drug-Target Kinetic and Thermodynamic Predictions 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.13.669965v2

3. AI Molecular Models: From One-Size-Fits-All to Specialized Departments

AI drug discovery has often felt like an attempt to build the ultimate “Swiss Army knife” that can solve every problem.

We throw all the molecules we can find—from rigid steroids to flexible peptides, from charged amino acids to greasy alkyl chains—into a single neural network. And then we expect it to magically learn all the rules of chemistry.

But we know chemistry doesn’t work like that. A tool for turning screws and a tool for cutting things have fundamentally different design philosophies. If you try to do everything with a Swiss Army knife, you end up doing nothing particularly well.

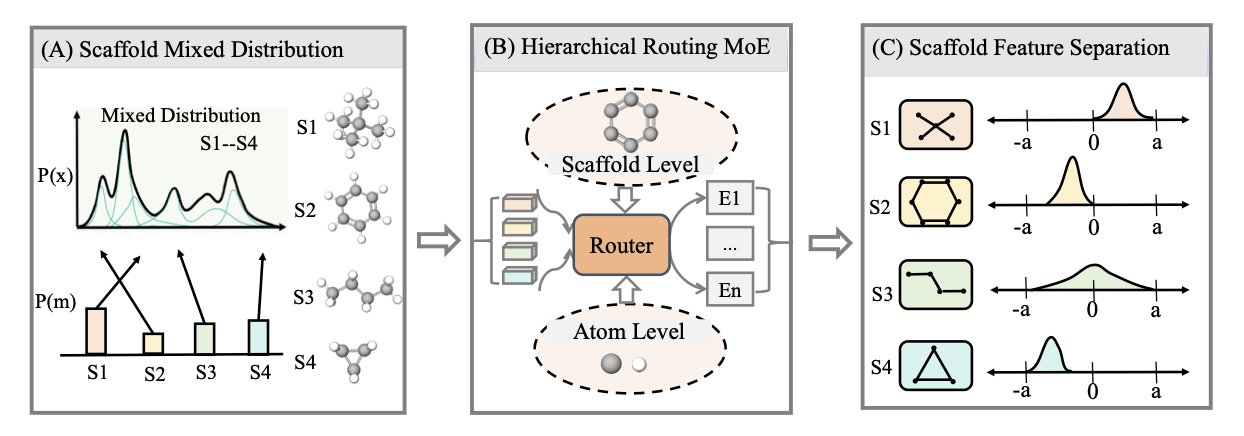

H-MoE builds a well-organized “corporation” for AI.

The idea is borrowed from the “Mixture-of-Experts” (MoE) models in natural language processing. This new model, Hierarchical MoE (H-MoE), adds a “corporate structure” that is very intuitive for chemists.

You can think of H-MoE as a company with an efficient front desk and multiple specialized departments. When a new molecule “walks in,” it first goes to the “reception desk.”

This “front desk” is the hierarchical “routing” system. The first thing it does is not to look at every atom and bond. It only looks at the molecule’s “ID card”—its core chemical scaffold.

“You’re an indole derivative? Okay, please head to the ‘Aromatic Heterocycles Department’ on the third floor.” “You have a penicillin scaffold? Please go to the ‘β-Lactam Antibiotics Department’ on the fourth floor.”

Only after the molecule is sent to the right “department” does the “expert” there—the AI sub-model specializing in that type of scaffold—begin its detailed analysis, studying every substituent and every chiral center.

So how does this “reception desk” learn to be so smart?

This is thanks to a “pre-job training” method called contrastive learning.

During training, you constantly show the “front desk” pairs of molecules. You show it two different indoles and tell it: “These two are relatives. You should send them to the same department.” Then, you show it an indole and a piperidine and say: “These two are unrelated. You should separate them.” After millions of these “family recognition” exercises, the “front desk” becomes a top-tier chemical classification expert that can identify molecules by their scaffold alone.

How does this “corporate” AI architecture perform?

It outperformed the “sole-proprietor,” single “Swiss Army knife” models in almost every aspect. It performs better when handling diverse molecular libraries and generalizes better to new molecules it has never seen before. This “company,” which only looked at 2D information, even performed better than some “sole proprietors” that had access to 3D structures.

This shows that a better organizational structure can sometimes be more important than simply piling on more information.

This work may represent a fundamental shift in how we think about and build molecular representation models. AIDD is moving toward a more pragmatic, modular, and truly “engineering” era that is closer to how we humans organize knowledge.

📜Title: Scaling Molecular Representation Learning with Hierarchical Mixture-of-Experts 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.09.669511v1