Table of Contents

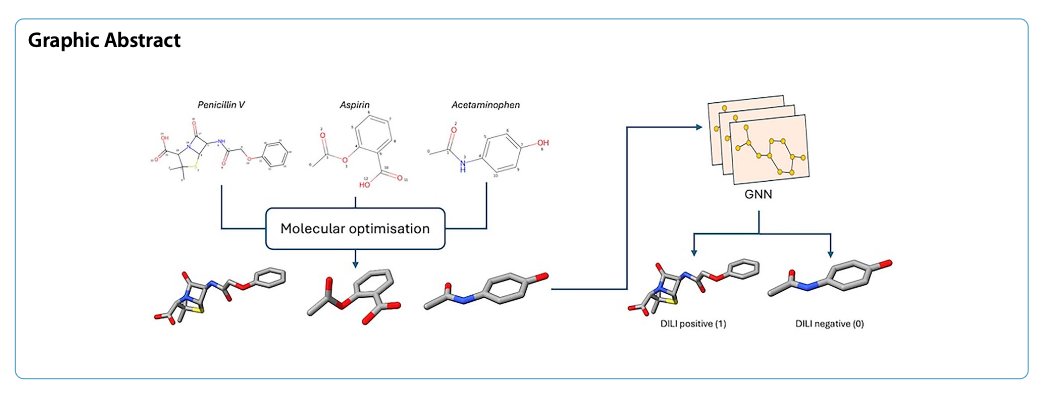

- By adding detailed chemical features from optimized 3D structures to a graph neural network, the DILIGeNN model achieved state-of-the-art performance in predicting drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

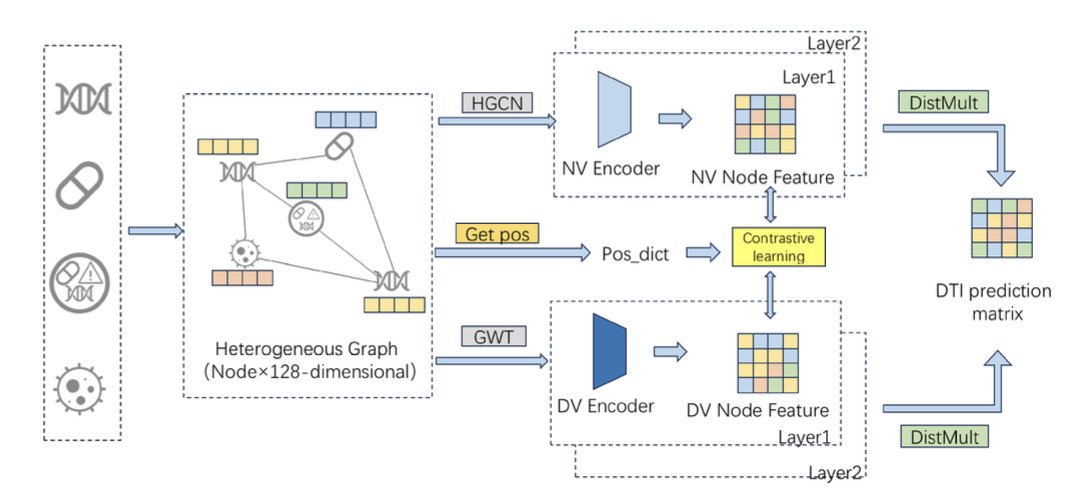

- GHCDTI combines graph wavelet transforms and contrastive learning to improve the accuracy of drug-target interaction prediction and is the first model to account for the dynamic flexibility of proteins.

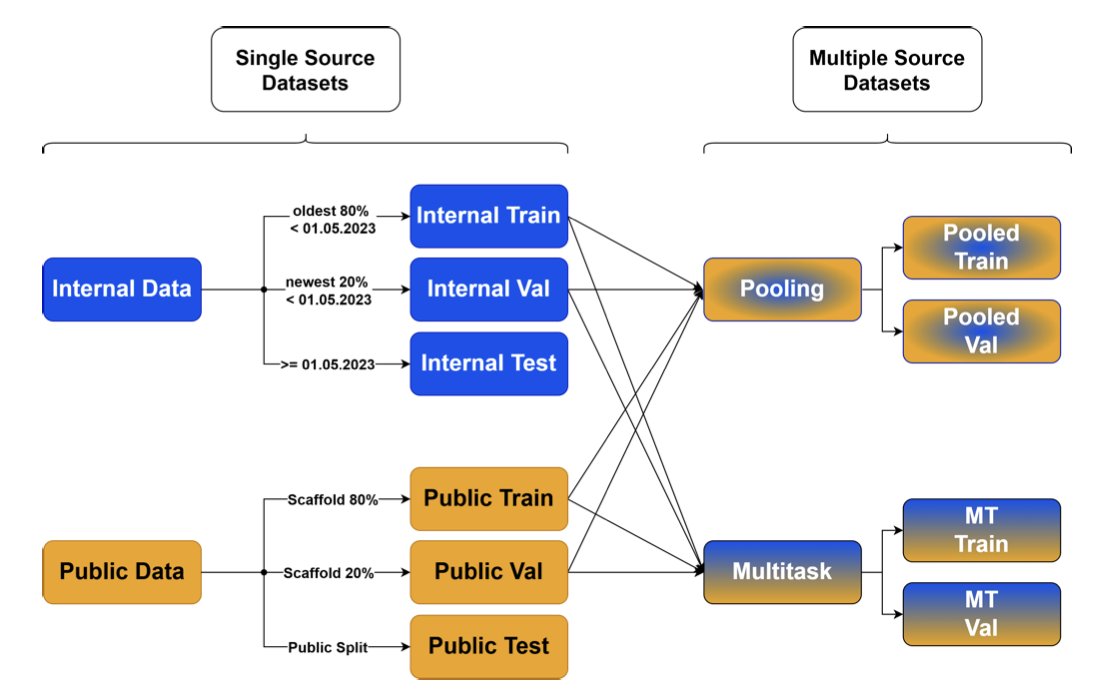

- A study from Merck shows that combining high-quality public data with internal company data, especially through multi-task learning, can significantly improve the accuracy and generalization of ADME prediction models.

1. DILIGeNN: Predicting Liver Injury with More Detailed 3D Features

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is a major roadblock in drug development. It often appears late in clinical trials or even after a drug is on the market, causing financial losses and serious public health problems. If we could use AI models to screen out molecules with DILI risk early in development, it would be a huge step forward.

Graph neural networks (GNNs) are popular for predicting molecular properties. But most GNN models work with pretty basic inputs. They usually only look at a molecule’s 2D connectivity—which atom is connected to which. This is like looking at a stick figure. You get the general shape, but you miss a lot of detail.

DILIGeNN’s Innovation: From Stick Figures to Detailed Blueprints

The DILIGeNN model in this paper aims to feed the GNN a much more detailed blueprint.

The idea is to “refine” a molecule before feeding it to the GNN. 1. 3D Structure Optimization: First, the researchers use computational chemistry methods to generate the lowest-energy 3D conformation for each molecule, which is closest to its real-world state. 2. Extract Detailed Features: Then, from this optimized 3D structure, they extract a series of features that traditional GNNs don’t use, like: * More precise bond lengths: A double bond is shorter than a single bond, and this geometric information is now explicitly given to the model. * Partial charges: Which atoms in the molecule have a positive or negative charge, and how those charges are distributed. * Atomic orbital hybridization types, and more.

These richer, more chemically realistic features are then used as the node and edge attributes in the graph, which is then fed into the GNN for training. It’s like we’re giving the model higher-quality ingredients with more useful information.

How Did It Perform?

The results show that the model fed with “refined” ingredients was indeed smarter than the one fed with “crude” ones.

On the crucial FDA DILI dataset, DILIGeNN achieved an AUC of 0.897. This is a very high score, surpassing other models previously reported.

The advantage of this method isn’t just for DILI prediction. The researchers applied the same approach to several other public benchmark datasets, including:

DILIGeNN achieved state-of-the-art or near state-of-the-art performance on all these tasks. This proves that providing more detailed chemical features is a generally effective strategy for improving GNN model performance.

In AI drug discovery, we shouldn’t just focus on algorithmic innovations. Getting back to the chemistry and thinking about how to provide models with higher-quality, more informative inputs is just as critical for improving performance.

DILIGeNN makes such accurate predictions relying only on a molecule’s chemical structure. This is very valuable for quickly screening and evaluating candidate compounds in the early stages of drug discovery.

📜Paper: https://jcheminf.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13321-025-01068-3 💻Code: https://github.com/tlee23-ic/GNN_DILI

2. GHCDTI: A DTI Prediction Model That Understands Protein Dynamics

Predicting which protein target in the human body a new small molecule will bind to—known as drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction—is the starting point of drug discovery. AI models, especially GNNs, are already pretty good at this. But most of them share a few common weaknesses:

- Proteins are treated as rigid bodies: Many models only look at a protein’s static 3D structure. But we know that proteins in the body are flexible and they move. Their conformational changes are often key to how they bind with drugs.

- Data imbalance: The amount of known drug-target binding data is a drop in the ocean compared to the vast chemical and protein space. Positive samples (they bind) are rare, while negative samples (they don’t bind) are countless. This can lead a model to just guess “no binding” for everything, which gives a high accuracy score but is useless to us.

- The black box problem: The model says a molecule will bind, but why? Which part of it plays a key role? Many models can’t answer this.

The GHCDTI model in this paper tries to tackle all three problems at once.

How to Make a Model See a “Dynamic” Protein?

GHCDTI uses a mathematical tool called a “graph wavelet transform.”

You can think of it like this: an image can be broken down into high-frequency signals (edges, details) and low-frequency signals (background, color blocks). Similarly, a protein’s structure graph can be decomposed into different “frequency” components using a graph wavelet transform.

By learning from both of these components at the same time, GHCDTI gets a more complete representation of the protein. It knows not only what the protein looks like, but also which parts of it tend to move. This is crucial for understanding how a drug interacts with a dynamic binding pocket.

Using Contrastive Learning to Fight Data Imbalance

To keep the model from taking the easy way out on the data imbalance problem, GHCDTI uses a “contrastive learning” strategy.

It generates two different “views” for each node (a drug or a protein): one from its topological structure and one from the wavelet transform mentioned above. Then, it forces the model to learn to make the representations of the same node in these two different views as similar as possible, while making them as different as possible from the representations of other nodes.

It’s like asking a student to read both the original and a translation of an article and then recognize that both tell the same story. This forces the model to learn more fundamental and robust features, rather than just memorizing superficial patterns.

Fusing Multi-Source Information for Better Interpretability

GHCDTI also fuses the drug’s 2D structure, the protein’s 3D structure, and known bioactivity data using a cross-graph attention mechanism. This attention mechanism acts like a pair of “X-ray glasses” for the model. It tells us which group on the drug and which region of the protein the model was mainly “looking at” when it made its prediction. This gives us direct clues for understanding and optimizing molecules.

The results show that GHCDTI achieved state-of-the-art performance on several benchmark datasets, and it also performed well in “cold start” scenarios (predicting for entirely new drugs or targets).

📜Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-16098-y

3. Merck’s Experience: Combining Public and Private Data Improves ADME Prediction

Every large pharmaceutical company sits on a gold mine: decades of internal compound and ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) data. Using this data to train AI models to predict the ADME properties of new molecules is a routine part of a researcher’s job.

But we’ve always faced a question: if we train a model on our own data, will it be accurate when predicting an external compound with a chemical structure completely different from our past projects? Conversely, can a model trained on a public database accurately predict our unique internal drug candidates?

The answer is often: not necessarily.

Models can become “specialized” and perform well only on data they are familiar with. This is known as the “Applicability Domain” problem.

This study from Merck conducts a very systematic and honest exploration of this problem.

How to Solve the Model’s “Specialization” Problem?

Their approach is: since sticking to one diet can lead to nutritional deficiencies, let’s have the model “eat” from both plates—combine public data and internal company data.

But how you combine them matters. 1. Pooled Single-Task: The simplest way is to just mix the two datasets together and train a single model. This sometimes works, but if the distributions of the two datasets are very different, or if the data quality is inconsistent, it can backfire and lead the model astray. 2. Multi-Task Learning: This was the best-performing method in the study. You can think of it like asking a student to learn two related but distinct subjects, like physics and chemistry. In the process, the student discovers underlying general principles (like the conservation of energy) that apply to both.

Multi-task learning works the same way. The model shares some network parameters at a lower level to learn the chemical principles common to all the data. At a higher level, it maintains separate “expert” modules for each dataset (public and private) to learn their unique structure-activity relationships (SAR). This way, the model learns both the “common ground” and the “specialty,” ultimately performing better at predicting on both datasets.

The Data Speaks for Itself

Merck’s researchers used their massive internal dataset, combined with high-quality public datasets like the one from the Biogen report, to model six key pharmacokinetic endpoints (like clearance, bioavailability, etc.).

In almost all tests, the models trained on the combined data, especially the multi-task models, outperformed those trained on a single data source. Both accuracy and reliability saw real improvements, whether predicting on the internal test set or the external public test set.

So first, don’t be insular. Even for a company like Merck with massive amounts of high-quality internal data, actively embracing and integrating external public data can still bring huge value. It broadens the model’s horizons, making it better prepared to handle new chemical scaffolds that may appear in future projects.

Second, multi-task learning is a powerful tool for handling heterogeneous data. It offers a more elegant way to fuse information instead of just crudely piling the data together.

📜Paper: https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv-2025-7sbr0