Table of Contents

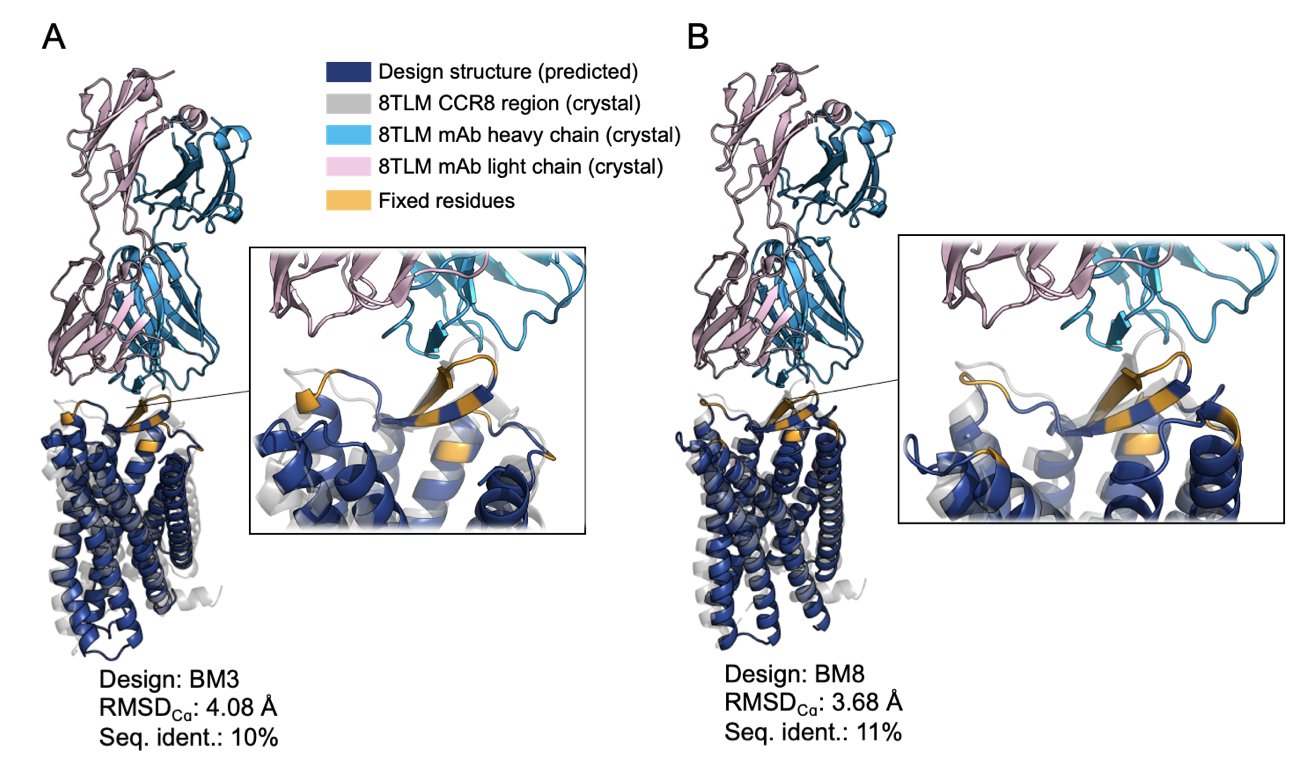

- Researchers successfully engineered the difficult membrane protein CCR8 into a water-soluble protein using de novo computational design. They did this while preserving the key antibody-binding site, clearing a major hurdle for GPCR drug development.

- SEAL makes Graph Neural Network predictions intuitive and trustworthy by breaking down molecules into chemical fragments and analyzing their contributions independently, solving the AI model’s “black box” problem.

- With plug-and-play modules for structure and property control, CMCM-DLM enables AI models to perform precise, customized molecular design without retraining.

1. Computationally Designing a Soluble GPCR to Tackle the CCR8 Drug Target

The GPCR (G protein-coupled receptor) family is a gold mine. Over a third of all approved drugs target them. But they are also notoriously difficult to work with because they are membrane proteins.

Think of a membrane protein as a greasy rock embedded in a soap bubble (the cell membrane). It naturally wants to stay in an oily environment. If you try to pull it out of the membrane and put it in a water-based solution, it becomes extremely unstable. It curls up like a scared cat, losing its original structure and function. This creates endless problems for subsequent work, like screening antibodies, running biochemical assays, and determining its structure.

This paper tackles that exact problem. The researchers chose a very popular immuno-oncology target: CCR8. CCR8 is highly expressed on tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells (Tregs), making it an ideal target for eliminating these “traitor” T cells in the tumor microenvironment. All the major pharmaceutical companies are working on it.

How do you turn “water-hating” into “water-loving”?

Instead of using traditional trial-and-error methods, the researchers used computational design to give CCR8 a complete overhaul.

Here’s their approach: 1. Preserve the core functional region: First, they defined their goal. They didn’t need the engineered protein to still send signals. They just needed it to be recognized by a specific antibody (mAb1). This meant they only had to preserve the correct conformation of the key antibody-binding surface (the epitope). 2. Replace everything else: For the rest of the protein, especially the “greasy” parts buried deep in the cell membrane, they used AI models like ProteinMPNN. This model’s job is to swap out hydrophobic amino acids for hydrophilic ones on a large scale. 3. Ensure structural stability: Of course, you can’t just swap them randomly. An AI structure prediction model like AlphaFold supervised the entire process to ensure the new amino acid sequence would still fold into the desired 3D shape, not just a useless lump.

It’s like copying a key for a specific lock. We don’t need to use the exact same metal as the original. We just need to make sure the key’s “teeth” have the right shape and arrangement. For the rest of it, we can use a more stable, easier-to-work-with material.

What were the results?

They designed and successfully expressed 13 water-soluble analogs of CCR8. The amino acid sequences of these new proteins had only 10-13% similarity to the natural CCR8. That basically makes them entirely new proteins.

But even this “unrecognizable” protein worked. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) tests showed its binding affinity to the target antibody mAb1 (KD values between 77-857 nM) was on the same level as the wild-type CCR8 (KD value of ~190 nM). This proved that the “key’s teeth” were perfectly preserved.

More importantly, these proteins could be produced at yields of over 70 mg/L. This is a very practical number. It means we can easily get enough stable protein for all kinds of downstream applications.

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.18.670068v1

2. The SEAL Model: Making GNN Molecular Predictions Less of a Black Box

These days, almost every project has a few AI models running. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have become popular for predicting molecular properties because they can directly process a molecule’s graph structure.

But we’ve all been in this awkward situation:

In a project meeting, a computational chemist presents a molecule predicted by a model to be highly active. As a medicinal chemist, you’d ask, “Why? Which part of the molecule is responsible? Where should I optimize next?” The computational chemist often just shrugs and says, “That’s what the model says.”

This is the biggest problem with GNNs—they are a black box.

They can give you an answer, but they usually can’t give you a convincing reason. For those of us who need to make critical decisions like “which molecule should we synthesize next,” this is of limited help.

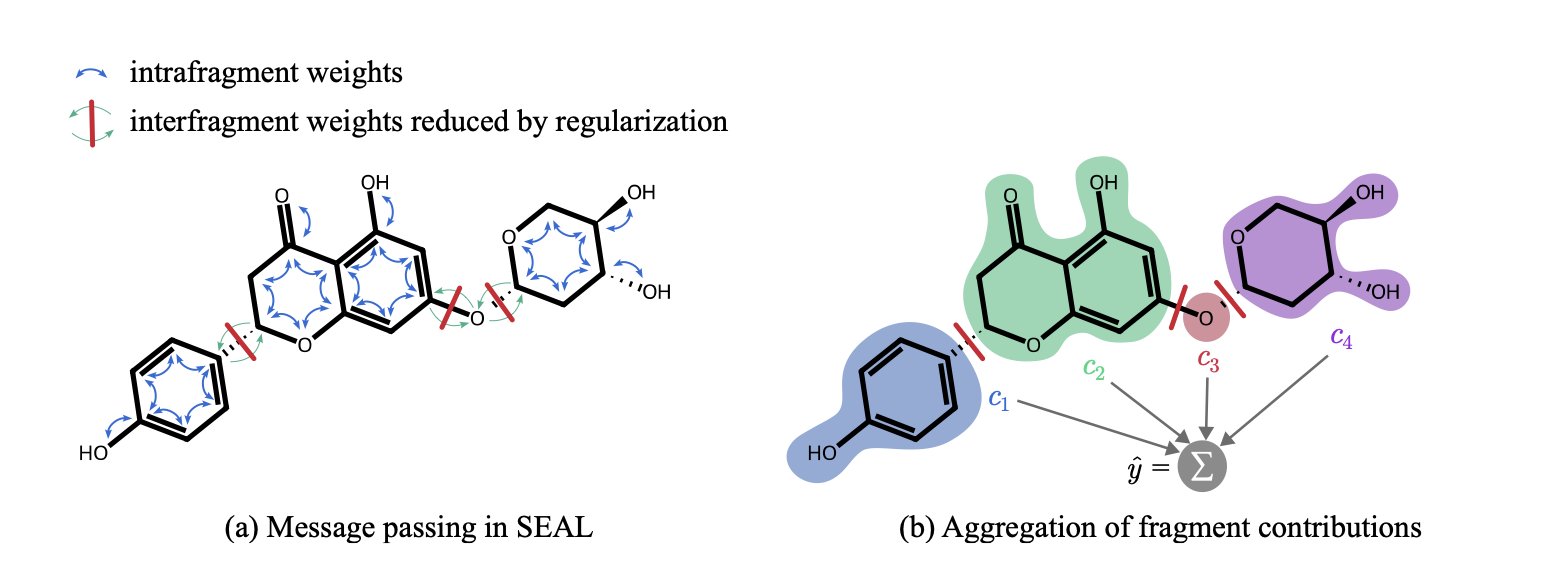

The SEAL model introduced in this paper was created for model explainability.

How does SEAL work?

Many past explainability methods try to “guess” which atom or bond was most important using post-hoc attribution methods after the model has already made its prediction. These methods can sometimes produce counter-intuitive results.

SEAL’s approach is different. It was designed for explainability from the very beginning.

Here’s how it works. In a standard GNN, information flows throughout the entire molecular graph, like a messy stew. Information from one atom can, after a few rounds of message passing, influence another atom far away. This makes it hard to tell who gets credit for what.

SEAL acts more like a city planner. It first breaks a large molecule into meaningful “neighborhoods” (chemical fragments) based on rules familiar to chemists, like functional groups and ring systems. Then, it builds “firewalls” between these neighborhoods within the model. Its GNN layers are specially designed to prioritize information flow within a neighborhood and strictly limit communication between neighborhoods.

This way, when the model makes a prediction, it’s actually first assessing the contribution of each “neighborhood” (chemical fragment) to the final property, and then summing up these contributions to get the total score.

What does this mean in practice?

When SEAL tells you a molecule has poor solubility, it can also provide an itemized “list of responsibilities”: the benzene ring contributed -10 points; the carboxylic acid group, +20 points; and this newly added piperidine ring, -30 points.

The medicinal chemist’s task becomes clear: the problem seems to be the piperidine ring. Let’s try replacing it in the next round.

The authors didn’t just prove their method’s superiority mathematically. They also ran a user study with domain experts. They anonymously showed chemists explanations from SEAL and other methods. The chemists generally agreed that SEAL’s explanations were more aligned with their chemical intuition and more helpful for making decisions.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.15015v1 💻Code: https://github.com/gmum/SEAL

3. AI Molecular Design: Finally Balancing Structure and Properties

Most drug discovery companies now have a few AI molecule generation models. These models are like junior chemists with endless ideas, capable of sketching out tons of novel molecular structures.

But problems arise. Sometimes, we ask a model to optimize around a specific scaffold, and it produces molecules with great properties (like good solubility and logP), but it has completely changed the core scaffold. Other times, we force it to preserve the scaffold, and it listens, but the properties of the generated molecules are terrible—like a “brick,” completely undruggable.

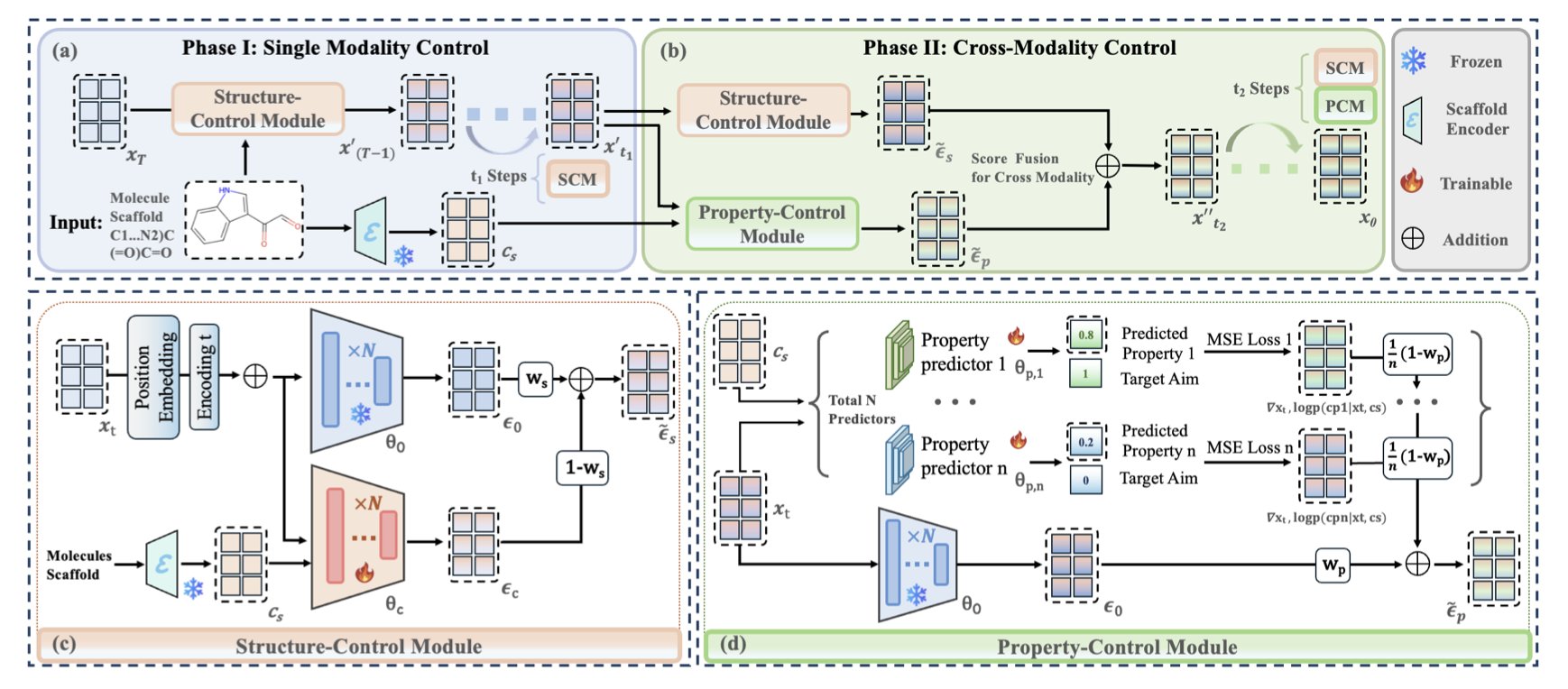

This awkward trade-off between “structure” and “properties” is a major pain point for current diffusion models based on the SMILES language. The CMCM-DLM framework proposed in this paper is here to solve this.

How do you get the best of both worlds?

The authors broke down one complex task into two simpler sub-tasks, executed in different stages of the generation process. You can think of it like building a house:

Phase 1: Building the frame (Structure Control Module, SCM) In the early stages of molecule generation, the structure is still fuzzy, like a chaotic electron cloud. This is when the SCM module steps in. Its job is simple: make sure the house’s load-bearing walls and main structure (the desired molecular scaffold) are put up first and in the right place. It places a “straitjacket” on the generation process early on to prevent the structure from going off track.

Phase 2: Finishing the interior (Property Control Module, PCM) Once the main frame of the house is stable, the PCM module takes over. It’s responsible for the “interior design”—adjusting the details without destroying the load-bearing walls. This means choosing the right windows, flooring, and paint colors. These details correspond to the molecule’s chemical properties, such as QED (drug-likeness), PLogP (lipophilicity), and SAS (synthetic accessibility). The PCM guides the later steps of generation to ensure the final molecule meets our property standards while satisfying the structural requirements.

Plug-and-Play

These two control modules in CMCM-DLM, the SCM and PCM, are designed to be “plug-and-play.” What does that mean? It means we don’t need to spend a lot of time and effort retraining a massive underlying diffusion model to use this new feature. We can just “plug” them into any pre-trained model like a USB device. This greatly lowers the barrier to adopting the technology, allowing this new method to be quickly applied to real projects.

The paper’s data is persuasive. Across multiple datasets, CMCM-DLM achieved an average scaffold similarity of 55% for generated molecules while improving target property satisfaction by 16%. When optimizing multiple properties at once, the relative improvement was 52%. These are not minor gains. For a medicinal chemist, this means the suggestions from AI have a lower failure rate and contain more usable “good ideas.”

CMCM-DLM gives us a more obedient and intelligent AI assistant for lead optimization. It can work within the “rules” we set (preserving the core scaffold) while maximizing its creativity to find that “ideal molecule” with the perfect structure and properties.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.14748