Table of Contents

- FROGENT integrates fragmented drug discovery tools into an automated AI agent. It not only performs well on multiple benchmarks but also shows its potential to go from target discovery to molecule design in a real-world case.

- The BLISS framework gets around the bottleneck of accessing individual-level data in proteomics. It uses easily available pQTL summary statistics to build powerful multi-ancestry protein prediction models, providing a new tool for drug target discovery.

- NetMD combines graph theory and time warping to give us a powerful new tool that can automatically align and compare multiple molecular dynamics trajectories without presets.

1. FROGENT: Can an AI agent really automate the entire drug discovery workflow?

Drug discovery often feels like a long relay race.

Biologists find a target and hand it off to chemists. The chemists synthesize a batch of compounds and pass them to the pharmacologists for testing. If any link in this chain breaks, the whole project stalls.

Over the years, many AI tools have appeared, but most are “point solutions.” One might predict a protein structure, another might design a molecular fragment. They are still disconnected.

Now, an AI agent called FROGENT aims to automate the entire process. So, what’s it all about?

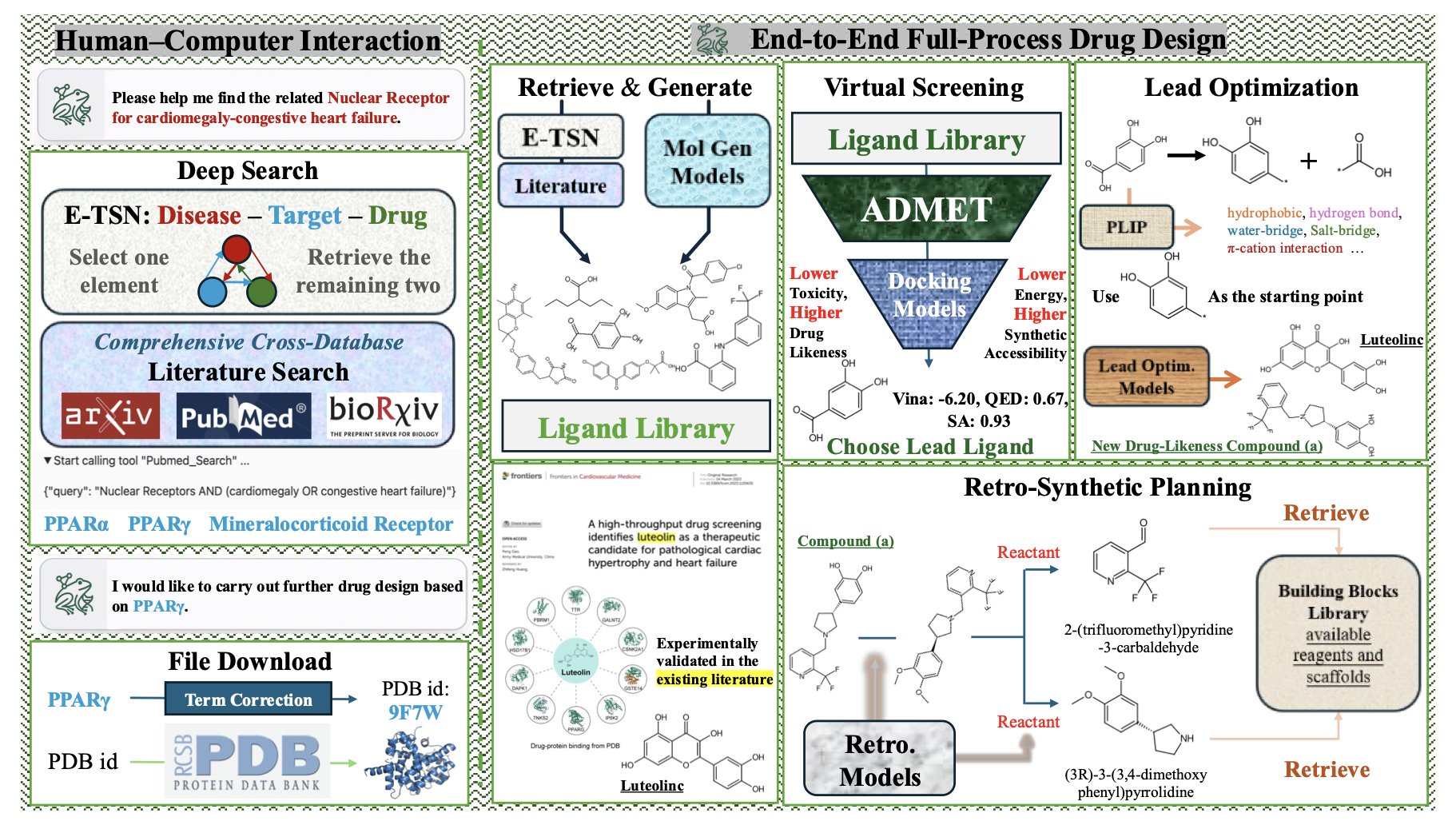

FROGENT’s architecture is like a well-organized toolbox. At the bottom is the database layer, which acts like an all-knowing librarian, integrating vast amounts of literature and structured biochemical data. In the middle is the tool layer, filled with “hardcore” computational chemistry tools we use every day, like molecular docking and property prediction libraries. At the top is the model layer, which houses a group of “expert models,” each specializing in a specific task like predicting ADMET or assessing synthetic feasibility. A Large Language Model (LLM) acts as the central coordinator, dynamically calling on these databases, tools, and models to assemble a complete workflow based on your request.

It sounds good, but the data has to back it up.

The researchers tested FROGENT on eight benchmarks covering the full drug discovery pipeline. In hit discovery, its performance was three times better than the previous best baseline. In interaction analysis, its performance doubled. These numbers surpass many well-known open-source and even commercial models. Benchmarks are just benchmarks, of course, but this result shows its fundamentals are solid.

A key design in the system is the Model-in-Context-Protocol (MCP). You can think of MCP as a universal power adapter. It establishes a standard that allows AI models and external tools to communicate smoothly. This means FROGENT isn’t picky; you can plug in any LLM or new computational tool that follows this standard. This design prevents it from becoming obsolete, because with tools in AI and computational chemistry evolving so fast, FROGENT can always be upgraded.

The most important question is whether it can do real work. The paper presents two case studies.

In the first case, they gave FROGENT a disease: cardiac hypertrophy and congestive heart failure. FROGENT mined the literature on its own and identified PPARγ as the target. It then designed candidate molecules from scratch. After a series of screening and evaluation steps, it proposed a novel compound with predicted properties superior to known molecules. The entire process, from target identification to molecule generation, was done autonomously.

The second case is closer to day-to-day optimization work. They gave FROGENT a known carbonic anhydrase II inhibitor and tasked it with “making it better.” FROGENT analyzed and modified the molecule, producing a new one with a higher predicted binding affinity and improved ADMET properties.

FROGENT is an ambitious attempt to integrate the complex and fragmented process of drug discovery into a single AI agent. It’s not meant to replace scientists but to act as a powerful research assistant. It can handle tons of tedious computation and information retrieval, freeing you to focus on the most critical decisions. If this model works as intended, it could significantly lower the barrier to computer-aided drug discovery, allowing more labs to participate in the early stages of creating new medicines.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.10760

2. The BLISS framework: Unlocking multi-ancestry drug targets with pQTL summary data

In drug development, we’re always searching for the key protein that links a gene to a disease.

Proteome-wide association studies (PWAS) are a great tool for this, but they have a problem: they depend on large-scale cohorts with individual-level genetic and protein expression data. Getting this data, especially when it involves sensitive personal information, is a major challenge that often stops research before it can start.

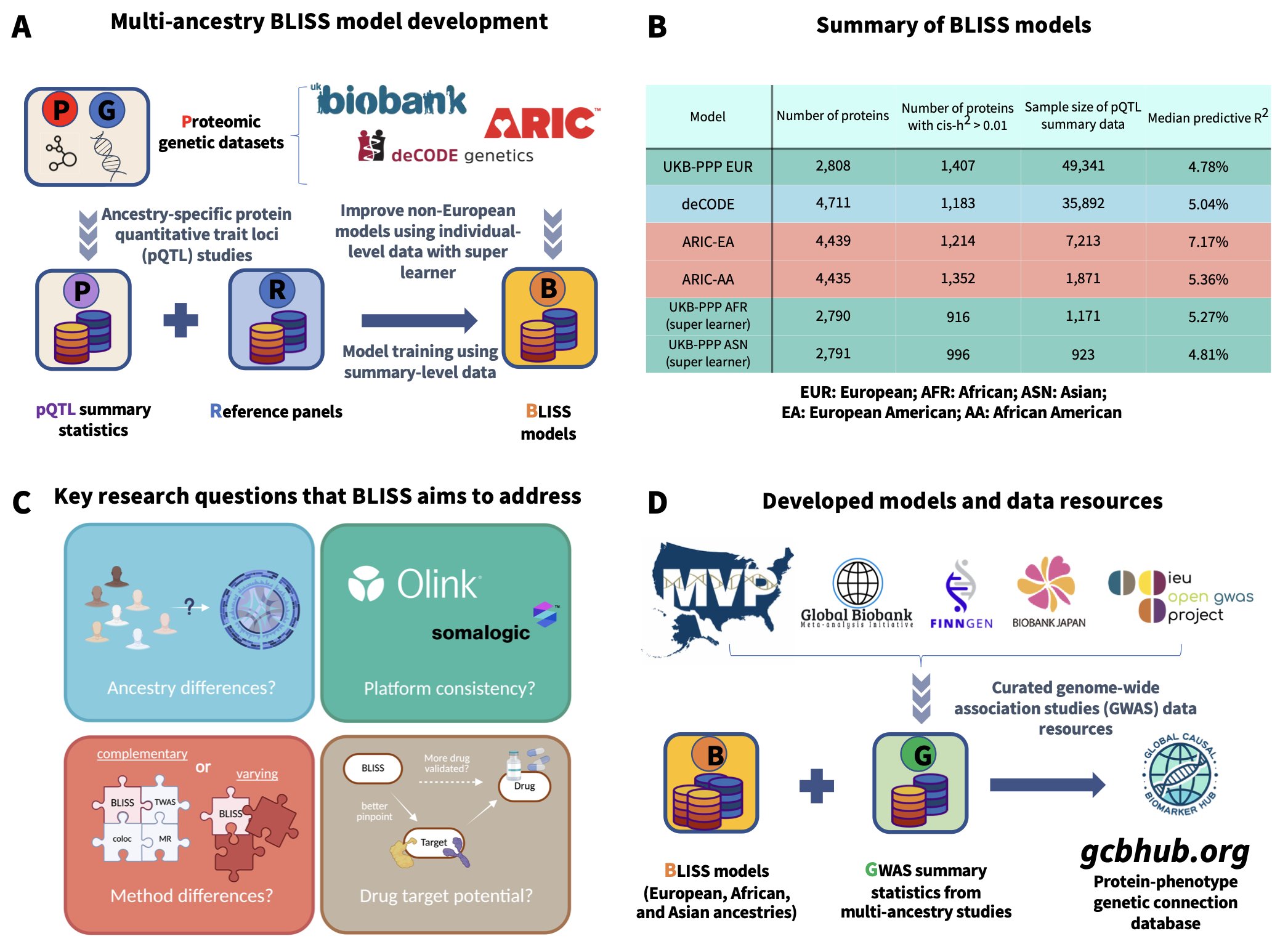

The BLISS framework offers a solution. The authors didn’t try to get their hands on hard-to-access individual data. Instead, they took a different path, focusing on more readily available pQTL summary statistics.

It’s like trying to figure out which ingredient combinations are most popular. You don’t need every chef’s secret recipe; you just need to analyze enough restaurant menus and customer reviews. BLISS does something similar. It uses the “recipe summaries” published by large studies like UK Biobank and deCODE—the association strengths between genetic variants and protein levels—to build its prediction models.

What’s powerful about this method is that it not only solves the data accessibility problem but also scales up massively. The researchers integrated multiple databases covering nearly 6,000 proteins to build a huge set of models for European populations.

But they didn’t stop there. We all know that drug development has long been plagued by Eurocentric data. A target that looks perfect in a European population might be ineffective or even cause side effects in other ancestries. The BLISS framework successfully extended its models to be multi-ancestry by integrating smaller datasets from Asian and African populations.

The models worked surprisingly well. When compared to traditional models trained on individual-level data, BLISS’s prediction accuracy was comparable and sometimes even better for proteins with high heritability. This might seem counterintuitive, but it could suggest that large-scale summary data has an inherent advantage in its signal-to-noise ratio.

Of course, what we really care about is whether it can find reliable targets.

The answer is yes. By analyzing over 2,500 phenotypes, BLISS not only rediscovered many known protein-disease associations but also uncovered new leads with clear ancestry-specific effects. For example, the strength and direction of many association signals differed significantly between European and African populations. This means future drug development must pay more attention to population diversity. Even more exciting, the potential targets identified by BLISS had a higher overlap with approved drug targets or clinically validated targets compared to other computational methods like TWAS and Mendelian Randomization (MR). It’s like a mining tool that not only finds ore but also tells you which deposits are easiest to extract and have higher commercial value.

The authors also did a comparison that many in the industry care about: data from the two major protein detection platforms, Olink and SomaScan. The results showed that the data from the two platforms are complementary, and using them together provides a more complete biological picture. This once again confirms that in the era of big data, integrating multiple data sources is the way to go.

The authors have made all their models and resources publicly available. This gives the entire research community a powerful tool, allowing more researchers without access to large biobanks to stand on the shoulders of giants and explore the complex relationships between proteins, genes, and diseases.

📜Title: Large-scale imputation models for multi-ancestry proteome-wide association analysis 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.10.05.561120v2

3. NetMD: Taming molecular dynamics trajectories with graph embedding

Running molecular dynamics (MD) simulations often leaves you with a bunch of independent runs. Each trajectory is like a narrator speaking a different dialect. The timelines don’t line up, and the order of key events is all over the place. Trying to piece together a clear, main storyline from this collection of “stories” is a nightmare. Traditional methods usually rely on pre-defined reaction coordinates, but that introduces bias—you only see what you’re looking for.

The NetMD method offers a solution to this problem.

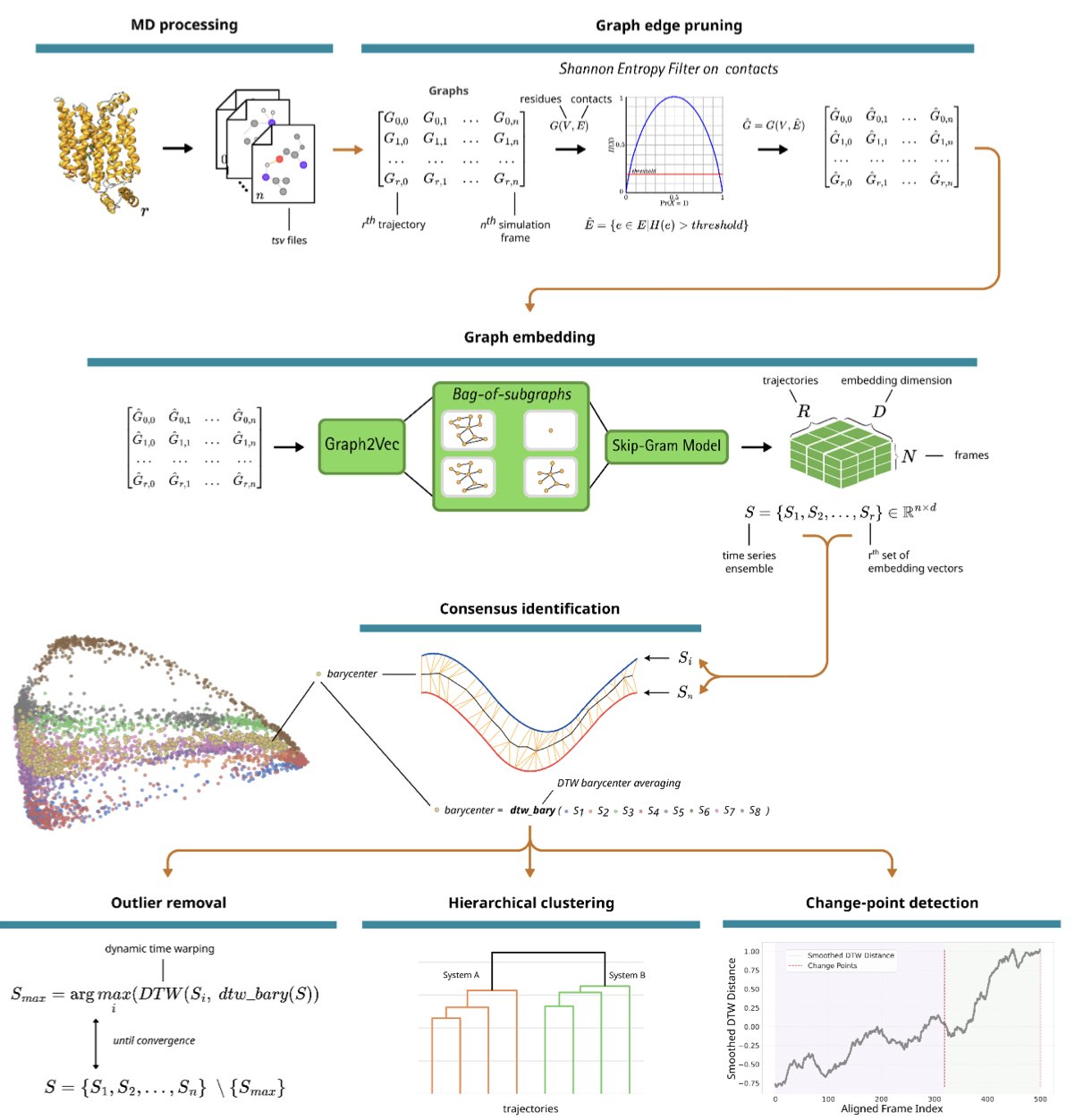

The authors’ idea was to stop focusing on direct comparisons of atomic coordinates. They took a different perspective, treating each frame of a protein’s conformation as a “social network.” In this network, each amino acid residue is a node, and if two residues are close enough, there’s an edge between them. This transforms the complex 3D motion of a protein into a series of “relationship graphs” that change over time.

But that’s not all. They then used graph embedding to compress each complex “relationship graph” into a low-dimensional vector—you can think of it as the unique “fingerprint” of that graph. Now, an MD trajectory that was once a chaotic sequence of tens of thousands of frames becomes a clean, time-ordered sequence of “fingerprints.”

With this sequence, the real magic begins. The authors introduced the Dynamic Time Warping algorithm. This algorithm is very good at aligning two sequences that move at different speeds, much like how audio recognition software can identify a song you hummed off-key. NetMD uses it to stretch or compress the timeline of the “fingerprint” sequences from different simulation trajectories until they align perfectly.

Through this process, NetMD can not only calculate a “consensus trajectory”—the story that all the simulations are telling together—but also precisely identify which simulations are “out of sync” or the exact moment a trajectory starts to “go off track.”

The researchers validated NetMD’s power on several challenging systems, such as the glucose transporter GLUT1 and the lysine-specific demethylase KDM6A. The results were impressive. The method automatically identified key windows of dynamic differences between wild-type and mutant proteins, and these windows corresponded to known conformational changes that affect function.

The entire process is “unsupervised.” You don’t need to give it any hints, like which pocket opening to watch or which loop’s movement to focus on. It can discover the most important dynamic events from the data on its own. This is hugely valuable for drug discovery. It can help us validate an existing mechanistic hypothesis or, when we’re clueless, point us in a new direction.

This tool is now open source. For computational drug discovery, it has the potential to become a standard part of the MD data analysis workflow. It frees us from tedious trajectory comparisons and lets us focus on understanding the biological story behind the molecule.

📜Title: NetMD: Unsupervised Synchronization of Molecular Dynamics Trajectories via Graph Embedding and Time Warping 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.12.669871v2 💻Code: https://github.com/mazzalab/NetMD