Table of Contents

- The Model Quality Assessment (MQA) competition at CASP16 shows that after AI predicts massive numbers of high-quality structures, the real challenge has shifted from “predicting” to “selecting”—how to pick the conformation closest to reality from thousands of similar models.

- HelixVS integrates a deep learning model into the traditional molecular docking workflow, solving the old problem of “right pose, wrong score” through precise rescoring and significantly boosting the efficiency of hit discovery.

- IBEX cleverly combines information theory and physics-based optimization to solve the persistent problem of data scarcity in drug discovery, enabling AI to generate reliable molecules with almost no starting data.

1. CASP16 Model Assessment: After AlphaFold, How Do We Separate the Good from the Best?

Ever since AlphaFold turned protein structure prediction from “nearly impossible” to a routine task, drug developers have faced a pleasant problem: we have too many structure models to look at.

Which of these models is the “true” structure that can actually guide our molecule design?

The Estimation of Model Accuracy (EMA) section of CASP16 tries to answer this question. It’s essentially the quality control department for the entire structure prediction field.

This year’s competition introduced a new twist called QMODE3. The rule was simple: participants were given thousands of very similar protein models generated by MassiveFold and asked to pick the best five. This made things much harder. It was no longer a simple “right” or “wrong” judgment but a nuanced assessment. Think of it like trying to find the few originals from a pile of high-quality fakes—it really tests your eye. This perfectly mimics the dilemma we face in real R&D: when given a bunch of AI models, which one do we trust?

The approaches from different teams were interesting.

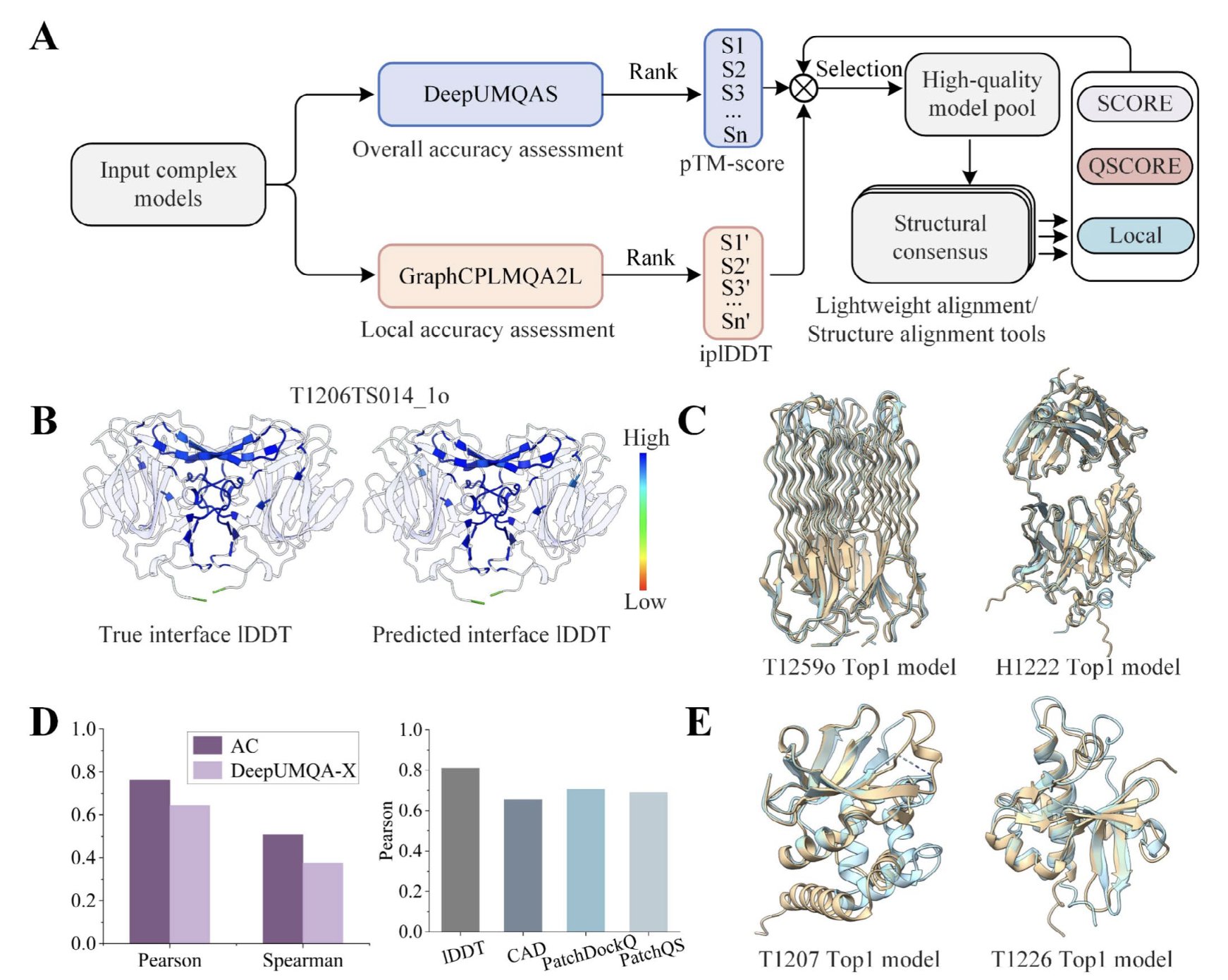

The MIEnsembles-Server team took first place in scoring folding accuracy. Their method, StrMQA, first uses their in-house DMFold to generate a set of high-quality “reference answers.” Then, it trains a machine learning model to compare how similar candidate models are to these references. This is a practical strategy, like having an experienced master craftsman judge a new apprentice’s work against a gold standard.

ModFOLDdock2, on the other hand, excelled at interface accuracy. This is especially important for drug discovery, since drugs often work at the interface of protein-protein interactions (PPIs). Their method is like a toolbox, integrating several new scoring functions, with versions optimized for specific tasks like ranking or scoring. This suggests that a single evaluation metric may no longer be enough; we need a combination of tools.

MULTICOM and GuijunLab represent the mainstream AI approaches. They used popular architectures like graph neural networks and Transformers to find clues about model quality from the features of individual models and pairwise comparisons between them. For instance, MULTICOM_GATE used a graph transformer to process both single-model features and inter-model similarities. GuijunLab developed a unified framework, DeepUMQA-X, that combines single-model methods with consensus strategies. These methods show the trend of using more complex and powerful algorithms to solve the problem.

But for me, the most insightful approach came from the Shortle group. Their method sounds a bit “back to basics.” They don’t use complex machine learning. Instead, they directly compare the AI-predicted models against a database of high-resolution X-ray crystal structures. They check if the most basic structural parameters—like bond lengths, bond angles, and amino acid side-chain conformation distributions—follow the statistical rules of real-world proteins.

This is like a seasoned structural biologist instinctively checking a new structure: “Does the position of this phenyl ring look a bit off?” or “Is this torsion angle in a rare region of the Ramachandran plot?” Although this method wasn’t the top performer in the competition, it offers a crucial perspective: no matter how sophisticated an AI model is, it must ultimately obey the fundamental laws of physics and chemistry. This gives us a “sanity check” based on first principles, independent of the AI black box.

So, the CASP16 assessment shows two trends. On one hand, people are diving deeper into machine learning with increasingly complex models. On the other, some are returning to fundamentals, trying to measure AI’s output with the yardstick of biophysics and chemistry.

📜Title: Highlights of Model Quality Assessment in CASP16 📜Paper: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/prot.70035

2. HelixVS: Giving Traditional Molecular Docking an AI Boost

Virtual screening is a test of both stamina and intellect.

We use molecular docking software, like the classic Vina, to screen millions or even hundreds of millions of molecules, trying to find a few “chosen ones” that bind to a target.

But the results are often frustrating. The binding poses generated by the software look plausible, but the scores are all over the place. Truly active molecules often get buried among thousands of “high-scoring duds.” It’s like panning for gold, only to find your magnet isn’t strong enough.

The HelixVS platform aims to give us a much stronger magnet.

The researchers know that tools like Vina are still workhorses for quickly generating lots of reasonable binding poses. Their weak spot is the scoring function, which tries to simulate complex intermolecular forces with a simple mathematical formula—and naturally falls short.

The HelixVS approach is to “let the specialists do their jobs.”

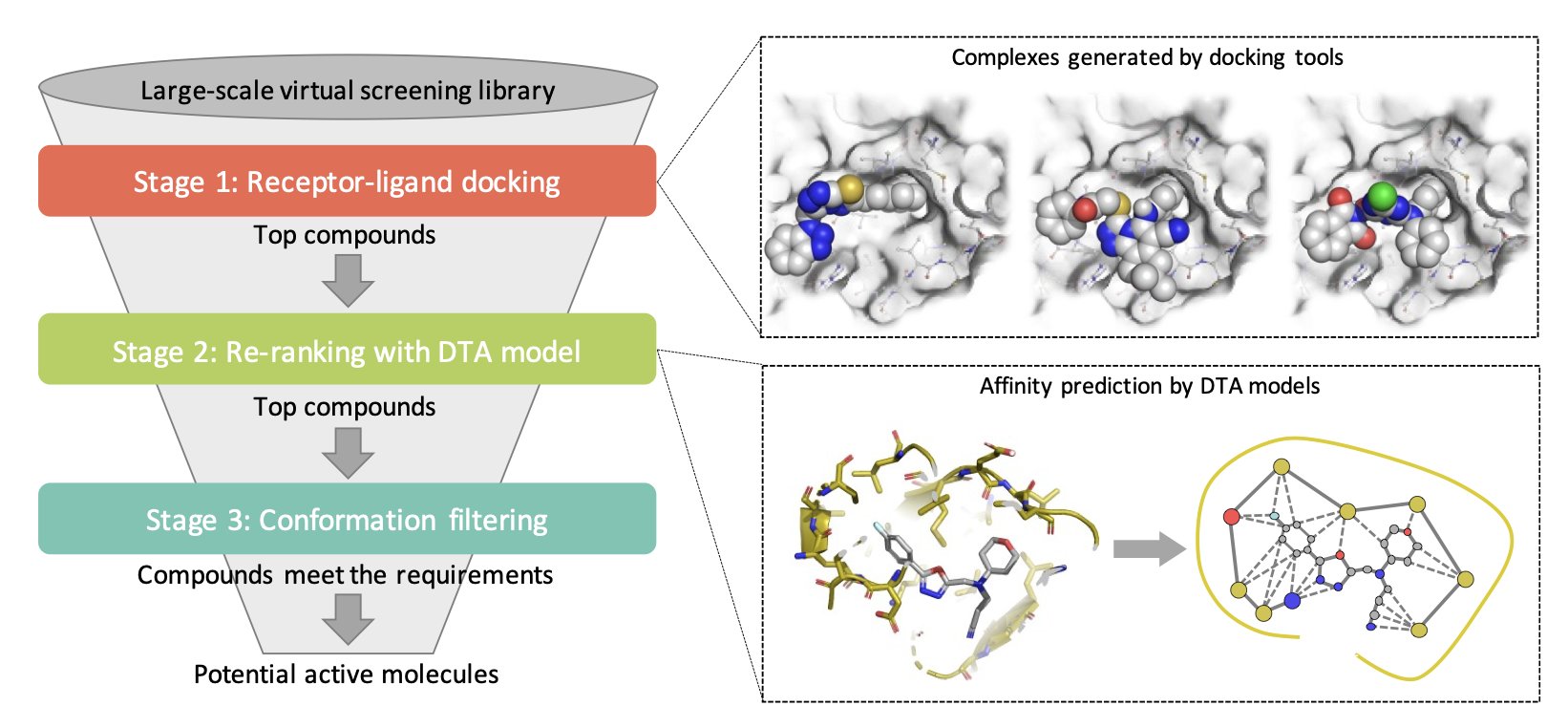

It breaks the screening process into a few steps:

First, it still uses old tools like Vina for the heavy lifting, quickly generating a large number of binding poses for compounds and their targets. The goal here isn’t precision, but comprehensiveness.

The second step is the core of the platform. It uses a scoring model trained with deep learning to re-evaluate all the poses generated in the first step. This is like bringing in an experienced expert to double-check the machine’s initial results. A deep learning model has seen far more complex data than any physics-based formula. It can “learn” more subtle binding patterns from the data, so its scores should theoretically be closer to the true binding affinity. This “rescoring” strategy directly targets the Achilles’ heel of traditional docking.

Third, there’s an optional conformation filtering step. This is very useful for medicinal chemists. For example, if we believe a specific hydrogen bond is key to activity based on known active molecules, we can add a filter here to keep only the poses that form this crucial bond. This integrates the chemist’s experience and intuition into the screening workflow.

So, how well does it work?

On the DUD-E benchmark, a standard in the field, HelixVS performed well, improving the enrichment factor by 2.6 times on average, and it was over ten times faster. But good benchmark results aren’t everything. What really makes this tool interesting is that the researchers applied it to four real-world R&D pipelines, with targets including CDK4/6, TLR4/MD-2, cGAS, and NIK—a diverse and challenging set of proteins.

The result? They found active compounds in every project, with activities ranging from micromolar (μM) to nanomolar (nM). This is not just theoretical; it proves that the “classic docking + AI rescoring” combo works in the real world. It can actually pull good stuff out of huge compound libraries.

The team also thought about implementation. They offer a free public version with limited computing power for academic users to try.

For companies in industry where data security is a top priority, they also support private deployment. This design approach shows they know their audience.

📜Title: HelixVS: Deep Learning Enhanced Structure-Based Virtual Screening Platform for Hit Discovery 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.10262v1

3. A New AI Drug Discovery Method: IBEX’s Secret to Generating Good Molecules from Small Data

In new drug development, especially for novel targets, we’re always fighting against a lack of data.

When we finally solve a protein-ligand crystal structure, the whole team celebrates. But that’s just one point in a vast chemical space. Trying to get an AI model to learn how to create new molecules from just one or a few data points is like asking someone who has read a single line of a poem to write a full sonnet. It’s just too hard.

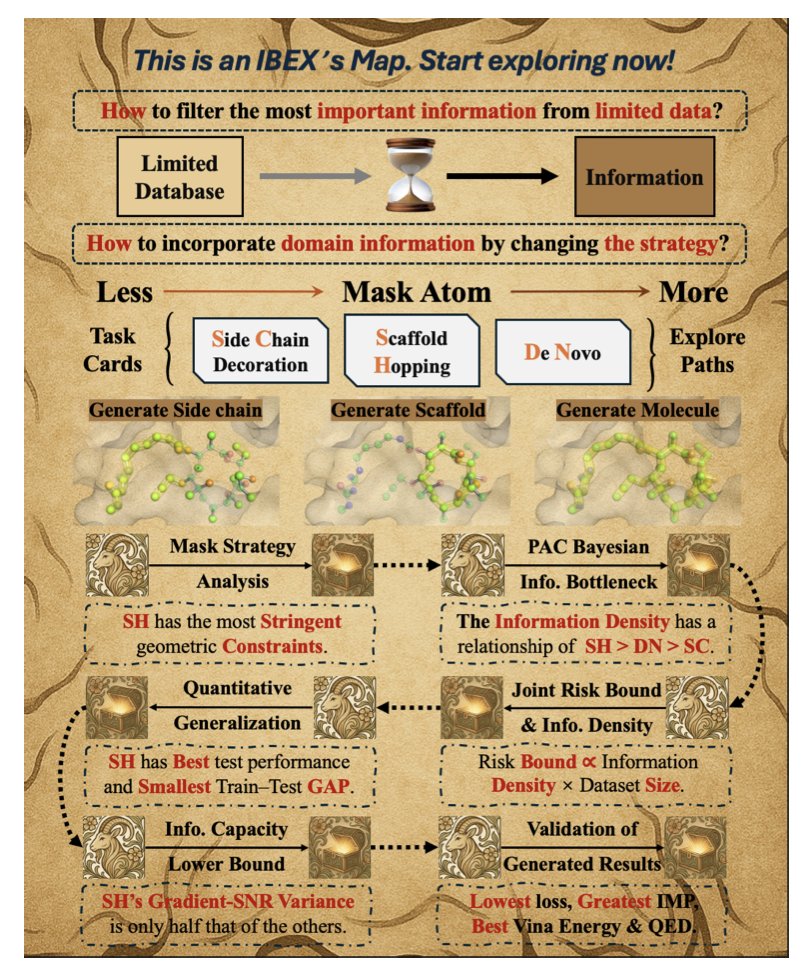

A recent paper on a method called IBEX explores what we should do when data is extremely scarce.

The authors’ idea is a two-step “coarse-to-fine” generation process, which aligns with a chemist’s intuition. In the first step, the model roughly generates a molecule that can fit into the protein’s binding pocket. This step doesn’t need to be perfect; the key is to get the molecule’s basic topology and 3D shape right, making sure it’s a good match for the pocket. This is like a sculptor using an axe to hew the general shape of a statue from a block of stone.

The second step, and the most important one, is the “refinement.” The model calls on a classic physics-based optimization algorithm (L-BFGS) to fine-tune the molecule’s conformation. This brings the rules of physical chemistry back to the table. The atom positions generated by AI might be geometrically reasonable, but they aren’t necessarily in their lowest-energy, most stable state. The physics-based optimization is like the sculptor switching to a small chisel to perfect every detail, ensuring the final molecule not only fits but also sits comfortably and energetically favorably in the pocket.

But a good workflow isn’t enough. IBEX also incorporates information bottleneck theory to explain why this approach is effective. The theory might sound a bit complex, but its core idea is simple: not all data is created equal. When you have very little data, every sample is precious. The authors found that for tasks like “scaffold hopping”—where the core scaffold is kept and only the surrounding R-groups are replaced—the strong geometric constraints mean each sample has a very high “information density.” In contrast, for “de novo generation,” the model has to learn too much from scratch, and the limited data is simply not enough. This provides important theoretical guidance for how we can design few-shot learning tasks in the future.

Of course, the results are what matter. IBEX improved the success rate of zero-shot docking from 53% to 64%, and the Vina score improved from -7.41 to -8.07 kcal/mol. Behind these numbers are savings in computational resources and higher-quality candidate molecules.

Even more interesting, the quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED) score increased by 25%. This means the molecules it generates not only bind well but are also more “drug-like,” rather than being strange creations that are impossible to synthesize or have poor metabolic stability.

The future of AI in drug discovery may not lie in endlessly piling up data and computing power, but in a deeper fusion of machine learning’s pattern-finding abilities with the classic principles of physical chemistry and information theory.

📜Title: IBEX: Information-Bottleneck-Explored Coarse-to-Fine Molecular Generation under Limited Data 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.10775