Table of Contents

- Large Language Models (LLMs) may be powerful, but when it comes to understanding complex biochemical reaction networks, they’re like new interns—far from having real chemical intuition.

- By using LoRA for “lightweight” fine-tuning of a large protein language model, ESM-LoRA-Gly significantly improves the accuracy of glycosylation site prediction while drastically cutting computational costs, making large-scale analysis possible.

- Researchers used a generative AI framework to successfully design completely new antibiotics that were effective against multi-drug resistant bacteria in animal models, proving AI can explore unknown chemical space to solve the difficult problem of drug resistance.

1. Large models don’t get protein pathways? A new benchmark reveals AI’s shortcomings

Every day, we deal with signaling pathways. If a certain kinase is inhibited, what happens downstream? If this protein is mutated, which metabolic pathway will it affect? We all have a complex network map in our heads. So, it’s natural to wonder if AI can help us sort through these connections, or even predict links we hadn’t considered.

Recently, a team put nine of the most popular LLMs to the test in a biochemistry exam.

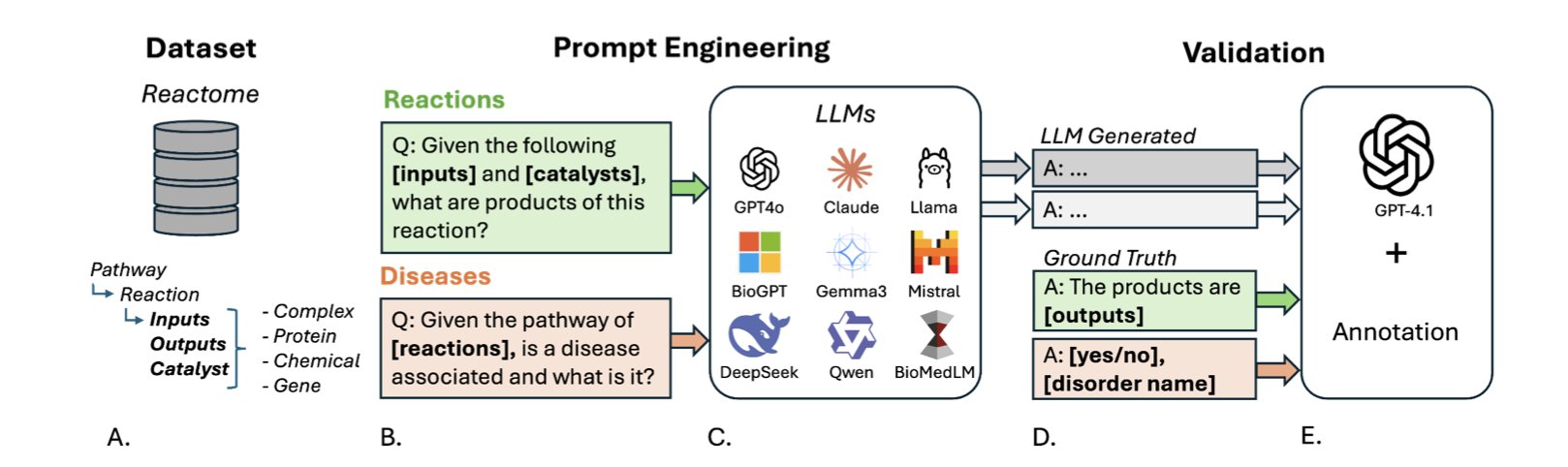

To make the test professional and fair, they built a new benchmark dataset called PathwayQA, based on the authoritative Reactome database.

The exam tested two things: predicting reaction products and linking pathways to diseases.

The first test was “chemical reaction reasoning”—given the reactants, predict the products. The result? Almost a total failure. Even the best-performing model had a median recovery score of only 0.6667, barely passing. It’s like a student who knows every word in the dictionary but is completely lost when asked to write a coherent essay. LLMs seem to remember a vast number of isolated entities (like protein A or molecule B), but they have a poor understanding of how these entities dynamically interact according to the laws of chemistry and physics.

The second test was “biological association analysis,” which involved matching signaling pathways with related diseases. The scores were slightly better here, but the average accuracy was only 0.5980, which isn’t great. But there was an interesting finding: the general-purpose, massive-parameter LLMs actually outperformed models specifically trained on biomedical literature. This is worth thinking about. Does it mean that for reasoning tasks that require integrating knowledge across different fields, sheer size—more parameters and broader general knowledge—is more important than narrow, specialized training? This is something for model trainers to consider.

The researchers also noticed that if a protein is a “social butterfly” involved in many reactions, the model’s prediction accuracy drops significantly. This makes perfect sense. Dealing with these “central hubs” in a network requires a global understanding of complex regulatory networks, not just simple pattern matching. Clearly, today’s models aren’t there yet.

📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.12.669911v1

2. LoRA + a large protein model: A “lightweight” breakthrough in glycosylation prediction

In biology, glycosylation is like adding different “outfits” to a protein, determining its function, stability, and location in the cell. Figuring out where these “outfits” are attached is crucial for understanding disease mechanisms and developing new drugs, especially biologics like antibodies. The problem is, predicting these sites, particularly O-linked glycosylation, has always been difficult—like finding a needle in a haystack.

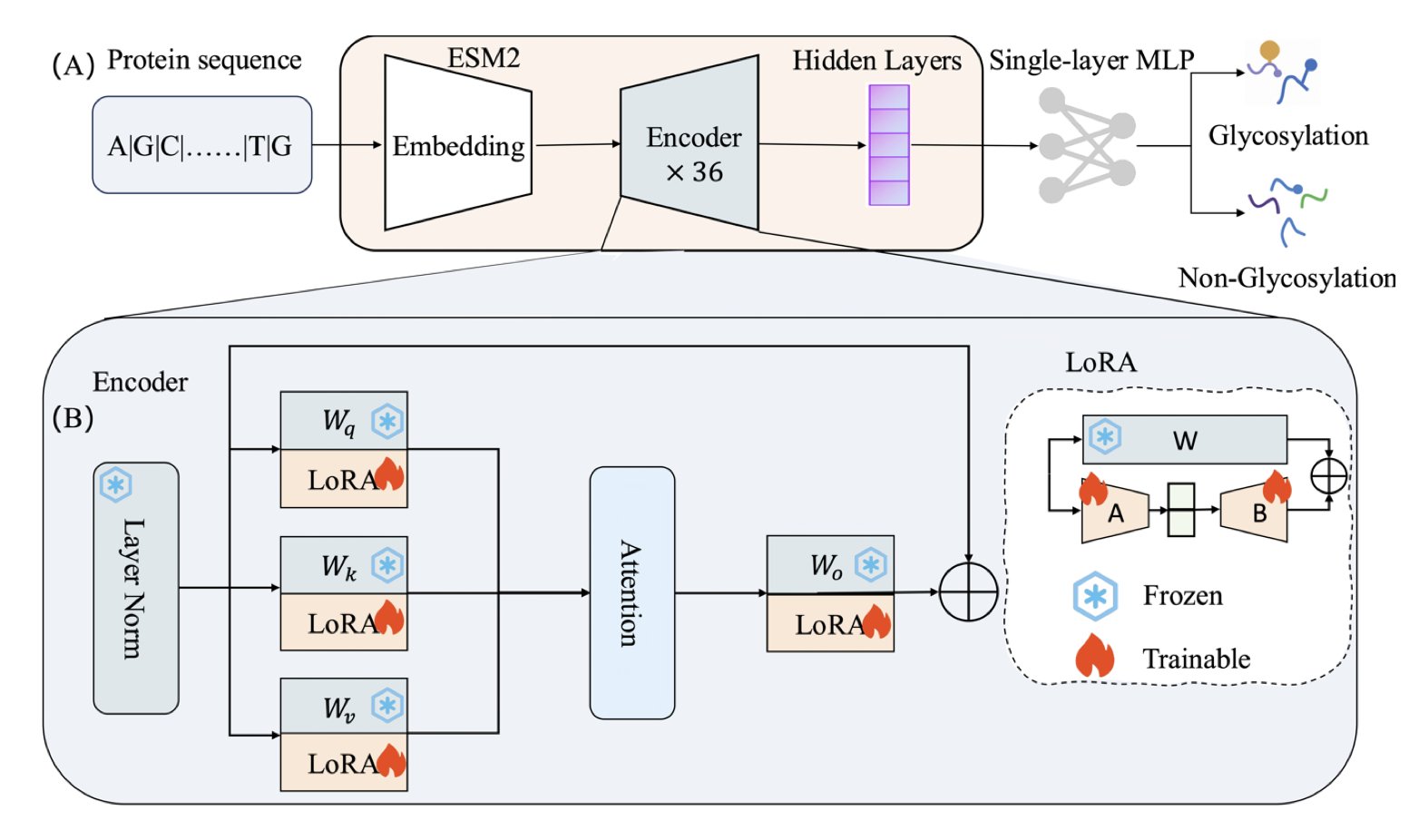

Now, the protein field has its own “GPTs”—large language models like ESM2. By learning from massive amounts of protein sequences, these models have developed a deep understanding of the “rules of protein language.” In theory, we could use them for downstream tasks like predicting glycosylation sites.

But doing this directly presents a practical problem: the ESM2-3B model has 3 billion parameters. Fully fine-tuning it for a small, specific task is like buying an entire hardware factory just to tighten one screw. The computational cost is absurdly high.

The ESM-LoRA-Gly method in this paper offers a solution. Instead of adjusting all 3 billion parameters, the authors used a technique called LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation). LoRA doesn’t change the original model’s massive parameter matrices. Instead, it adds two much smaller “patch” matrices alongside them. During training, only these two small patches are updated. It’s like adding a few sticky notes to a huge reference book instead of rewriting the whole thing. The effect is surprisingly good. The model learns the new task without a significant increase in computational load.

The results for the notoriously hard task of O-linked glycosylation prediction were impressive. The new method’s MCC score (a comprehensive metric for classification models) more than doubled, leaving previous state-of-the-art methods behind. For N-linked prediction, the AUC-PR reached 0.983, which is very reliable.

This means we finally have a tool that is both accurate and fast, enabling large-scale glycosylation analysis at the proteome level. Whether it’s for screening new drug targets or optimizing glycoengineering for antibody drugs to improve efficacy and half-life, this tool could be very useful.

📜Title: ESM-LoRA-Gly: Improved prediction of N- and O-linked glycosylation sites by tuning protein language models with low-rank adaptation (LoRA) 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.12.669850v1

3. AI designs new antibiotics from scratch, validated in animal models

The antibiotic development pipeline is running dry. This isn’t news. For decades, we’ve been modifying the same classic chemical scaffolds, and the “low-hanging fruit” is long gone.

This paper claims that scientists used AI to design entirely new (de novo) antibiotics that were effective in animals. Is this for real?

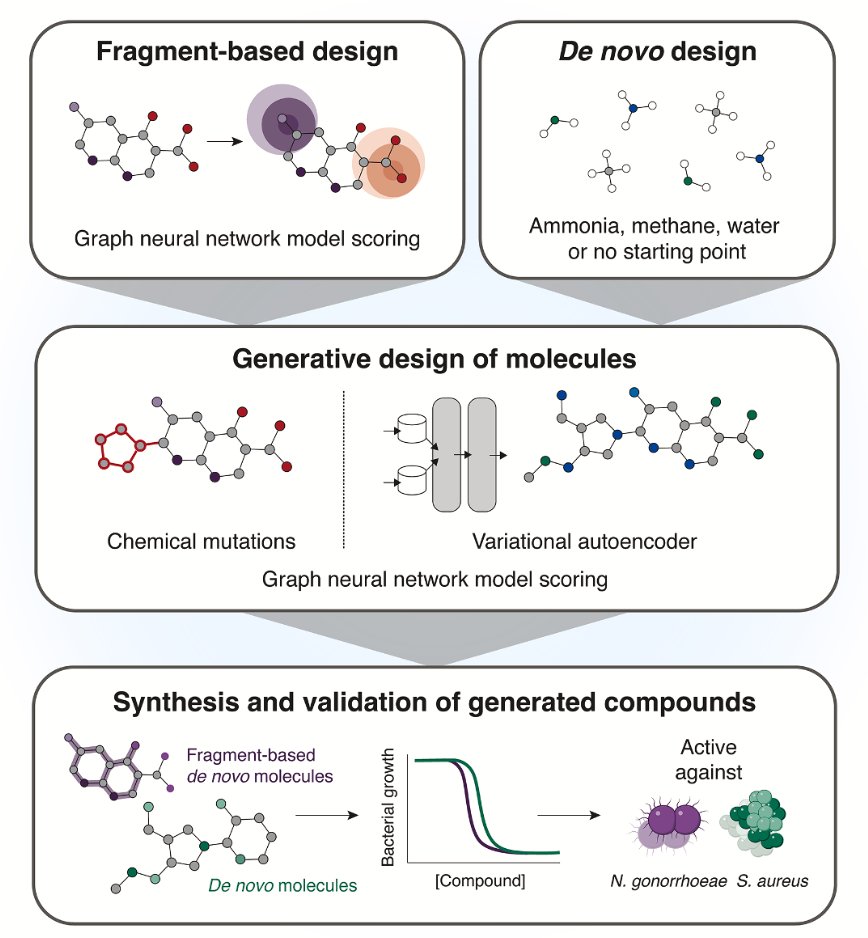

The authors used two different generative AI strategies.

The first is “fragment-based growth.” This isn’t a new concept in medicinal chemistry. You start with a known, slightly active “fragment” and build it out into a full drug molecule, like assembling LEGOs. But the key here is that they didn’t have chemists do the building; they had AI tools like genetic algorithms and variational autoencoders (VAEs) do it. It’s like giving the AI a small piece of a puzzle and asking it not only to complete the picture but also to make sure the final picture “makes sense”—meaning it has antibacterial activity.

The second method is more ambitious: “unconstrained de novo generation.” This is like giving the AI a blank sheet of paper and letting it freely create molecules it thinks will be antibacterial. This is where AI gets exciting—it has the potential to break out of the box of human chemical thinking and create structures we’ve never imagined. Of course, this is also where things can easily go wrong. Many of the molecules AI “draws” are either impossible to synthesize or completely useless.

From the computer-designed molecules, they selected 24 for synthesis, and 7 of them showed selective antibacterial activity. For exploring brand-new chemical space, that hit rate is quite good.

The most impressive results came from two star molecules: NG1 and DN1.

NG1 specifically targets Neisseria gonorrhoeae—a drug-resistant bacterium that’s a major headache for public health departments. Its mechanism is straightforward: it messes with the bacterial cell membrane, reducing its fluidity and eventually causing the entire membrane to lose its integrity. You can think of it as popping a balloon rather than trying to dismantle its complex internal machinery.

The perpetual challenge with this membrane-attacking strategy is selectivity: how do you ensure you’re only popping the bacteria’s balloon and not harming our own human cells? The paper’s data shows that NG1 has low toxicity, which is a good start. More importantly, it actually worked in a mouse infection model.

The other molecule, DN1, showed broad-spectrum activity against Gram-positive bacteria, including MRSA. This demonstrates that the AI platform isn’t just getting lucky with one molecule; it has the capability to generate different solutions for different targets.

So, what does this mean?

First, it’s a powerful proof of concept. It shows that today’s AI tools are not just for theoretical exercises; they can actually complete the entire process from algorithm to effective results in an animal model. This is a breakthrough from 0 to 1.

Of course, these are just lead compounds. They are a long way from becoming actual approved drugs. The subsequent studies on pharmacokinetics and toxicology, as well as the long and expensive clinical trials, are all minefields. But the most valuable part of this work is the AI platform itself.

📜Title: A Generative Deep Learning Approach to De Novo Antibiotic Design 📜Paper: https://www.cell.com/cell/abstract/S0092-8674(25)00855-4