Table of Contents

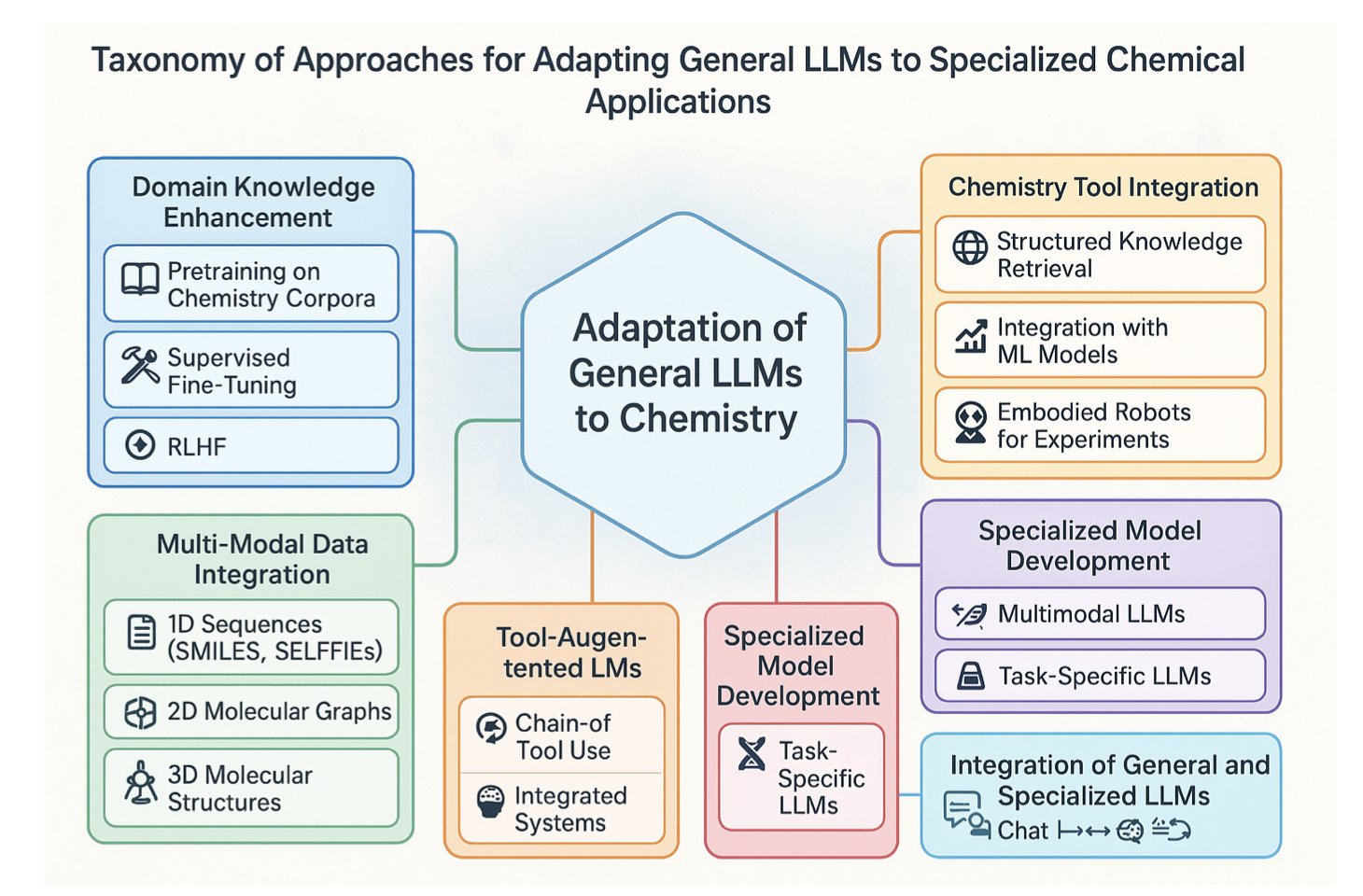

- Large Language Models are evolving from “chemistry consultants” who only work on paper to “autonomous researchers” who can plan, execute, and optimize chemical reactions in a robotic lab.

- David Baker’s team released the AtomWorks framework and RF3 model. They not only keep pace with AlphaFold3 in performance but, more importantly, provide foundational tools for the whole field through a modular, open-source ecosystem.

- A new open-source platform called AdaptiveFlow efficiently screened a 69-billion-molecule library. It discovered a nanomolar inhibitor for FSP1 and solved its first-ever co-crystal structure, providing a solid starting point for this difficult target.

1. AI in the Fume Hood: From Prediction to Autonomous Synthesis

Organic synthesis has always had a gap. On one side, you have the reaction scheme on paper or a screen—flawless, with a 100% yield. On the other side, you have the flask in the fume hood—the one with the suspicious color that refuses to react or just turns into a brown, gooey mess. We’ve always dreamed of a tool to bridge that gap.

When Large Language Models (LLMs) first appeared, they seemed like another flashy computational tool. They could look at a reaction and predict its yield based on what they learned from tons of literature. That’s cool, but to an experienced chemist, it’s like a robot that only recites recipes. It can’t actually help you cook.

But this review paints a very different and exciting picture of the future. AI is stepping out from behind the computer screen, putting on a lab coat, and walking into the fume hood.

Evolution, Phase One: From “Fortune Teller” to “Strategist”

In the past, you gave AI reactants A and B, and it told you the probability of getting product C. It was like a fortune teller. Now, you can show an LLM the final target molecule—a complex drug candidate—and ask, “How do we make this, step-by-step, from cheap, commercially available starting materials?” The model will start performing “retrosynthetic analysis,” breaking down the complex target into a series of feasible, logical chemical reactions, just like an experienced strategist. It’s learning the most central and creative skill in our field.

Evolution, Phase Two: From “Strategist” to “Field Commander”

But that’s not the most exciting part. What makes this real is connecting LLMs to the lab robots, automated dispensers, and real-time analytical instruments (like NMR, mass spec, and IR) that we’re already familiar with.

This creates a “closed loop.”

Imagine this scenario: 1. Plan: The LLM devises what it thinks is the best synthetic route for the target molecule. 2. Execute: It sends instructions to the robots in the lab. Robotic arms start precisely transferring solvents, weighing starting materials, and controlling the temperature. 3. Monitor: After the reaction starts, real-time spectrometers in a flow cell send a “snapshot” of the reaction mixture back to the LLM every few seconds. 4. Learn and Optimize: The LLM analyzes this real-time data and sees the reaction is slower than expected. It makes a judgment: “Hmm, maybe we should raise the temperature by 5 degrees, or add a bit more catalyst.” Then it sends new instructions to the robots.

This is like having a top-tier chemist who never gets tired, never needs to sleep, and can oversee hundreds of reactions at once. It’s no longer just giving you a static plan before the experiment starts. It’s performing dynamic, real-time, data-driven optimization during the experiment.

We’re not there yet

Of course, before we hand over the lab keys to an AI, there are a few very tricky problems to solve.

First is the “garbage in, garbage out” problem. LLMs learn from published chemical literature. And chemical literature suffers from “publication bias”—we only publish successful reactions with great yields. The thousands of failed attempts that only produced a pile of tar never make it into the AI’s training set. This is like teaching a new driver by only showing them videos of F1 champions winning races, without ever telling them about crashes or breakdowns.

Second is the “black box” problem. An AI might give you a brilliant synthetic route, but when you ask “Why did you think of that?” it can’t answer. It can’t discuss reaction mechanisms, transition states, or electronic effects like a human chemist. This “knowing what, but not knowing why” is a big problem in scientific exploration.

Finally, and most importantly, is the safety issue. Could an unrestrained LLM, in its optimization process, “invent” a route that produces an explosive intermediate or a highly toxic byproduct? We must design strict “safety guardrails” for it, ensuring all its operations stay within known, safe chemical space.

LLMs won’t replace organic chemists anytime soon. But they are becoming an unprecedentedly powerful partner. They will free us from repetitive, labor-intensive optimization work, allowing us to think about the bigger, more creative chemical problems that AI can’t yet touch.

📜Title: Large Language Models Transform Organic Synthesis From Reaction Prediction to Automation 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.05427

2. RF3 and AtomWorks: More Than Just Another AlphaFold3 Competitor

The David Baker lab has another preprint out. When you see RosettaFold-3 (RF3) in the title, your first reaction might be: another model chasing AlphaFold3?

Yes, but not entirely.

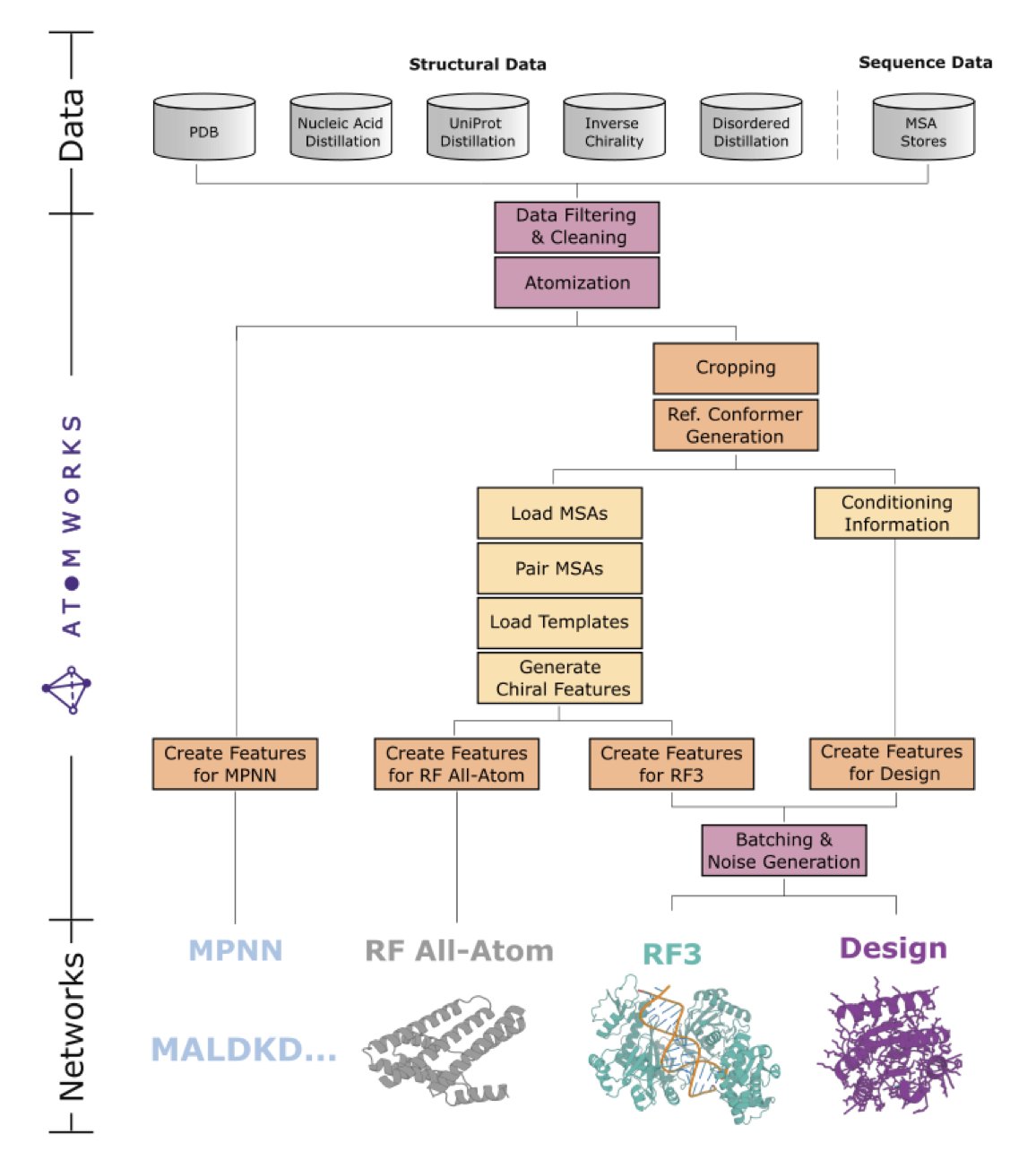

In my view, the real star of this paper is the AtomWorks framework.

Any fancy algorithm is ultimately built on data. Processing biomolecular data, especially the raw data pulled from the PDB, is like cleaning out a dusty old attic. Incorrect bond orders, missing charges, lost atomic coordinates… these trivial but fatal issues can trip up even the most sophisticated model.

AtomWorks does this “dirty work.” It builds a standardized data processing pipeline that turns messy input files into clean, organized “ingredients” ready to be fed to a model. The framework is like a LEGO set for biomolecular modeling. Its different modules (data processing, featurization) can be swapped and combined, letting researchers quickly test new ideas instead of starting from scratch every time.

RF3 is the first star product built with this “LEGO” set. Its performance is strong, and it has closed the gap with AlphaFold3 on many tasks, which itself proves the success of the AtomWorks framework.

But for drug discovery, a few points are especially worth noting.

First is chirality. Can a machine tell left from right?

This is a life-or-death question in small molecule drug design. The wrong enantiomer can turn a medicine into a poison. RF3 does a great job here, achieving 88% accuracy in predicting ligand chiral centers, slightly higher than AlphaFold3’s 84%. This seemingly small advantage could be immensely valuable in a real project.

Second is flexibility. RF3 allows users to apply “atom-level conditional constraints.” What does that mean? For example, if you know from experiments (like NMR) that a specific atom on a protein is close to a specific atom on a ligand, you can directly “tell” this to RF3. It will then factor this constraint into its structure prediction. This turns the model from a closed black box into a tool that can interact with experimental data. Whether for docking or for folding a protein into a specific conformation, this feature makes RF3 exceptionally practical.

So, RF3 offers more than just an open-source alternative to AlphaFold3. More importantly, the Baker team has opened up the entire “kitchen”—the AtomWorks framework, the trained models, and even the processed datasets. They haven’t just given us a fish (RF3); they’ve shared the fishing rod and the fishing techniques (AtomWorks) with everyone.

📜Title: Accelerating Biomolecular Modeling with AtomWorks and RF3 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.14.670328v1 💻Code: https://github.com/RosettaCommons/atomworks

3. AdaptiveFlow: Mining a 69-Billion-Molecule Library for an FSP1 Inhibitor

Drug discovery has always been a numbers game, but today’s numbers are getting absurd. The number of drug-like molecules we could theoretically synthesize is larger than the number of atoms in the universe. What we can actually access is just a drop in the ocean.

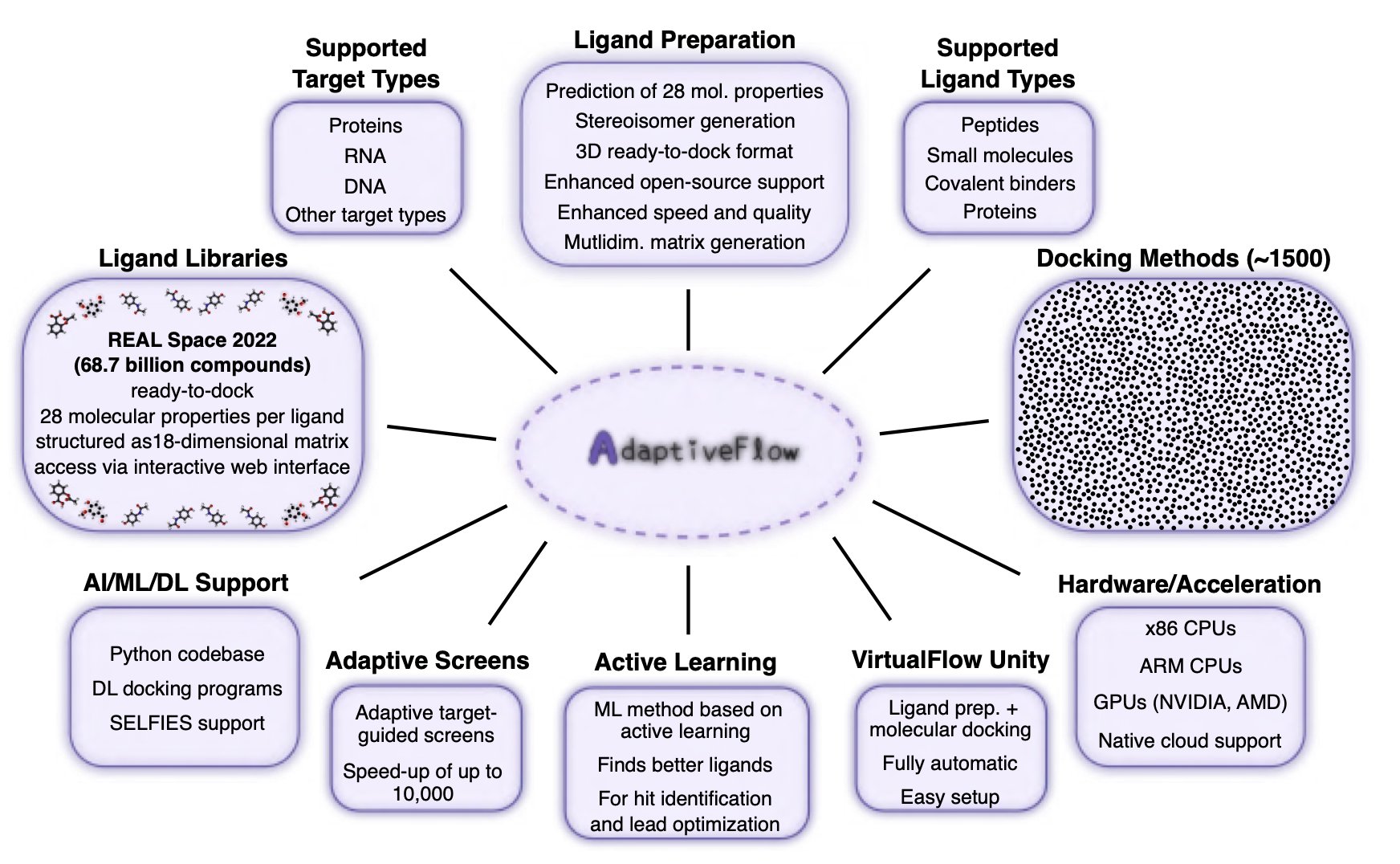

AdaptiveFlow can perform virtual screening on a library of 69 billion molecules.

The biggest hurdle in ultra-large-scale virtual screening (ULVS) is computational cost. If you try to use traditional docking methods to “test” billions of molecules one by one in a target’s binding pocket, the cost in resources and time is enough to make any project leader give up. AdaptiveFlow takes a smarter path. Instead of starting with “brute-force” docking, the researchers first did a quick “reconnaissance” of the entire chemical space using a multi-dimensional grid of molecular properties.

It’s like trying to find a person who meets specific criteria in an entire country. Do you go door-to-door, or do you first pull up a map, use key filters like age, occupation, and region to narrow it down to a few key cities or even neighborhoods, and then do your in-person search? AdaptiveFlow does the latter. This pre-filtering focuses the computation on the most promising regions of chemical space, cutting costs by about 1,000-fold.

The entire platform is built on the cloud and can use millions of CPU cores in parallel, which is an impressive engineering feat in itself. Best of all, it’s open-source. This means researchers in academia and at small biotech companies can now use this kind of “heavy artillery” that was once only affordable for large pharmaceutical companies.

Of course, no matter how good a platform sounds, you have to see if it can catch “fish.” This time, they targeted two proteins: PARP-1 and FSP1.

PARP-1 is an old friend with approved drugs on the market. But FSP1 (ferroptosis suppressor protein 1) is a trickier, more modern target. It’s a key protein in the ferroptosis pathway and plays an important role in diseases like cancer, but it has lacked good small molecule tools and drug starting points.

AdaptiveFlow not only found nanomolar inhibitors for both targets—which is already an excellent result for a purely virtual screening project—but the follow-up on FSP1 is what’s really important. The researchers successfully solved the co-crystal structure of their FSP1 inhibitor bound to the target protein.

This is the most exciting part of the story. A “hit” compound without structural support is like a treasure map with just a vague mark. You know the treasure is roughly “in that forest,” but how and where to dig is largely a guess. A co-crystal structure, on the other hand, is a blueprint with centimeter-level precision. It shows you exactly how your molecule fits into the protein’s pocket, which group forms a hydrogen bond with which amino acid, and which part has room for optimization. This turns drug discovery from “blind guessing” into “precision guidance.”

This is the first time anyone has obtained a co-crystal structure of FSP1 with a small molecule inhibitor. It not only validates the reliability of AdaptiveFlow’s screening results but also lights a beacon for everyone in the world who wants to work on the FSP1 target.

📜Title: AI-Enhanced Adaptive Virtual Screening Platform Enabling Exploration of 69 Billion Molecules Discovers Structurally Validated FSP1 Inhibitors 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.04.25.537981v2