Table of Contents

- This AI doesn’t just predict molecular activity. It’s also trained to explain “activity cliffs,” one of our biggest headaches, which finally makes it feel like a colleague you can talk to.

- By first learning “general chemical knowledge” and then undergoing “specialized training” on a small antibacterial dataset, this transfer learning framework successfully sifted through over a billion molecules to find new sub-micromolar antibacterial drugs.

- This AI framework uses GFlowNets to generate rare drug-drug interaction (DDI) samples to “balance” the training data, so the prediction model learns to recognize more than just the common cases.

1. AI Finally Learns to Explain Chemistry’s Trickiest “Cliff” Problem

Let’s talk about “activity cliffs” in medicinal chemistry—where two molecules look like twins, but their activity is worlds apart. This is a nightmare for traditional AI models.

Imagine you’ve designed and synthesized a molecule with good activity, say 10 nanomolar. You confidently think, “If I swap this methyl group for an ethyl group, adding one carbon should improve hydrophobicity and double the activity!” But after two weeks of work, you test the new molecule and get 10 micromolar activity—a 1000-fold drop. Your perfect hypothesis shatters.

Our current AI models are basically useless when they encounter these cliffs. They either ignore them or give a wildly wrong prediction, shrugging their shoulders and leaving you with an unexplainable black box. An AI that can’t tell you “why” has very limited value in drug discovery. We don’t need a fortune-teller that just spits out numbers; we need a colleague who can discuss their thought process with us.

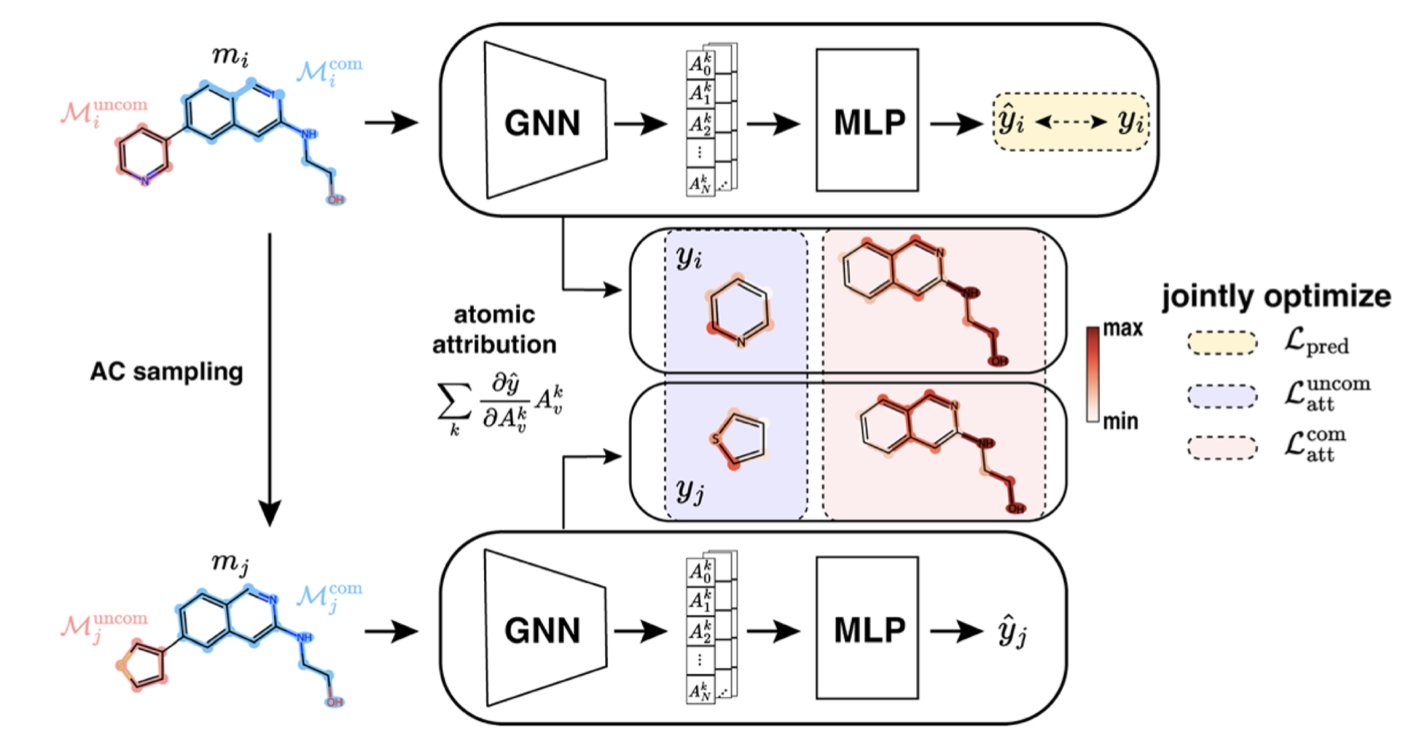

ACES-GNN is an AI that tries to understand and explain “activity cliffs.”

During training, it isn’t just fed a pile of molecules and their activity data to figure things out on its own. It’s also given an “answer key” compiled from chemists’ explanations for these cliffs. For example, for an activity cliff pair, a chemist might point out: “See, the only difference between these two is this chlorine atom. It’s likely forming a key interaction with an amino acid in the protein’s pocket, causing the huge difference in activity.”

ACES-GNN is forced to learn this kind of explanation. Its loss function includes a term that penalizes incorrect explanations. If the AI focuses on some irrelevant tail of the molecule instead of the critical chlorine atom, it gets “points deducted.” It’s like a strict teacher who demands not just the right answer but also the correct, logical steps to get there.

What’s the result of this approach?

First, the “attribution maps” generated by the AI—which show which parts of the molecule it thinks are most important for activity—have become highly consistent with chemists’ intuition. The AI is starting to “speak our language.”

When an AI is trained to “explain” a problem better, its ability to “predict” also improves. The data in this paper shows that ACES-GNN consistently outperforms standard GNN models (without explanation training) in both prediction accuracy and attribution quality across 30 different drug targets. This suggests that forcing an AI to grasp underlying causal relationships, not just surface-level correlations, makes it more powerful and robust.

So, are we about to have an all-knowing AI chemist? Not so fast.

This method depends on a supply of high-quality “human explanations” for activity cliffs as training data, which is not easy to get. And it’s still just a model. It will still make mistakes.

📜Title: ACES-GNN: Can Graph Neural Network Learn to Explain Activity Cliffs? 📜Paper: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2025/dd/d5dd00012b 💻Code: https://github.com/Liu-group/XACs

2. AI “Borrows a Brain” to Screen Drugs, Finding New Antibiotics in a Billion-Molecule Library

Finding new antibiotics is one of the most urgent medical challenges of our time.

The “superbugs” (ESKAPE pathogens) are becoming increasingly drug-resistant, while our new drug pipeline is as dry as the Sahara. A major reason is that traditional screening methods are like finding a needle in a haystack—extremely inefficient.

AI-powered virtual screening offers new hope. In theory, we can rapidly evaluate billions of molecules on a computer, identify the most promising candidates, and then validate them in the lab. But this introduces a new problem: training a good AI prediction model requires a lot of high-quality, known antibacterial activity data. And this type of data is very scarce and valuable.

This creates a chicken-and-egg paradox: to find new drugs, you need a good model; to train a good model, you need a lot of data on existing drugs.

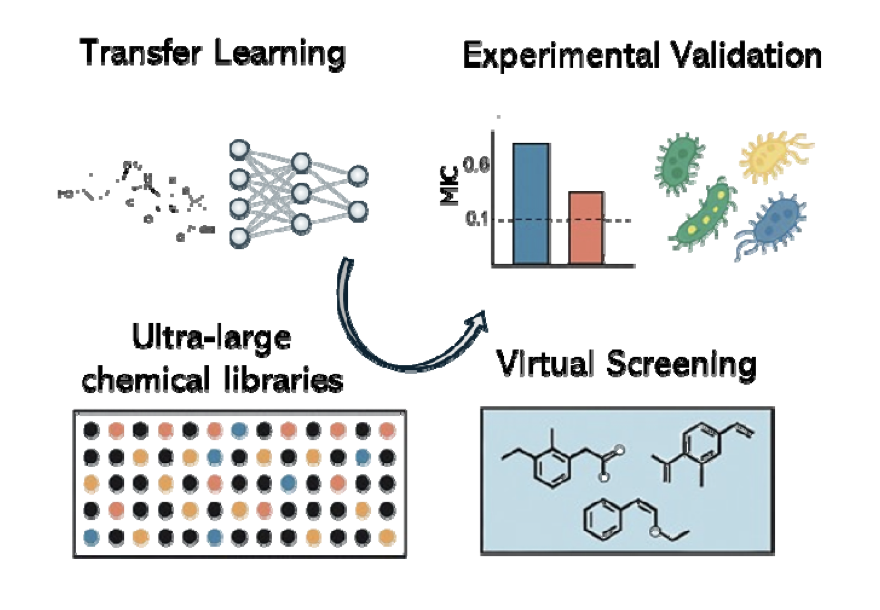

This new paper from bioRxiv shows us a way to break this paradox, using a method called transfer learning.

The concept is common in our own learning. A student who has mastered physics will usually learn chemistry faster than a complete beginner. That’s because they already understand many underlying, transferable concepts like atoms, energy, and interactions. They don’t have to start from scratch.

The research team did something similar with their deep graph neural network (DGNN) model.

- Step One: General Education (Pre-training). Instead of throwing the model straight into the data-scarce “antibacterial major,” they first gave it “general education” textbooks that were massive in volume but completely unrelated to antibacterial activity. These included:

- Docking scores for a huge number of molecules: This teaches the model what kinds of molecular shapes fit well into protein pockets.

- Binding affinities for a huge number of molecules: This teaches the model what kinds of chemical groups are likely to interact with proteins. At this stage, the model isn’t learning “how to kill bacteria.” It’s learning the more fundamental, universal “language of chemistry” and the “physical laws of molecular interactions.” It becomes a well-rounded “chemistry generalist.”

- Step Two: Specialized Training (Fine-tuning). Once the model completed its “general education,” it was sent to the “antibacterial major” for specialized training, where the data is scarce but highly specific. They used the hard-won, real-world antibacterial screening data to fine-tune this already knowledgeable model. Because the model already had a solid chemical foundation, it no longer needed thousands of examples to learn the features of antibacterial molecules. With just a few dozen or hundred examples, it could quickly “transfer” and “adapt” its general knowledge to this specific new task.

How well did this “generalist first, specialist second” strategy work?

They used the trained model to screen the ChemDiv and Enamine commercial compound libraries, which contain over one billion virtual molecules. The model selected 156 of the most promising candidates.

Then came the exciting part: they actually synthesized or purchased these molecules and tested them on E. coli. The result was a hit rate of 54%! This means more than half of the compounds picked by the model showed real antibacterial activity. This kind of success rate is almost unimaginable in traditional drug screening.

More importantly, many of the discovered compounds showed potent sub-micromolar activity, and some even had broad-spectrum antibacterial effects. Structurally, they also included novel chemical scaffolds, which means the AI successfully guided us to unexplored regions of the “chemical universe.”

This provides a powerful example of how we can use AI for drug discovery in a “data-poor” field. Sometimes, the best approach isn’t to keep fishing in the same small pond. It’s to first teach your AI the general skill of “swimming” and then drop it into any pond you’re interested in.

📜Title: Transfer Learning Enables Discovery of Submicromolar Antibacterials for ESKAPE Pathogens from Ultra-Large Chemical Spaces 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.07.669197v1

3. AI spars with itself to master rare drug interactions

In clinical pharmacology, drug-drug interactions (DDIs) are a constant challenge. When a patient takes multiple drugs at the same time (which is very common in older adults), these drugs can “fight” with each other in the body, leading to reduced efficacy or even serious side effects. Accurately predicting which drug combinations are dangerous is critical for patient safety.

Of course, we want to use AI for this. But there’s an obstacle called class imbalance.

Imagine you’re training an AI to recognize animals. You show it one million pictures of cats, one hundred thousand pictures of dogs, but only one picture of a capybara. The result is predictable: the AI will become an expert cat recognizer and a decent dog recognizer, but it will probably classify anything that looks vaguely like a rodent as a cat, simply because it has seen so few capybaras.

DDI datasets are just like this. Data for certain types of interactions, like drugs metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme, is abundant. But for other rare yet potentially fatal interactions, like the inhibition of certain transport proteins, there might only be a handful of data points. A model trained on such skewed data will naturally become a “specialist” in common interactions while being blind to rare but important risks.

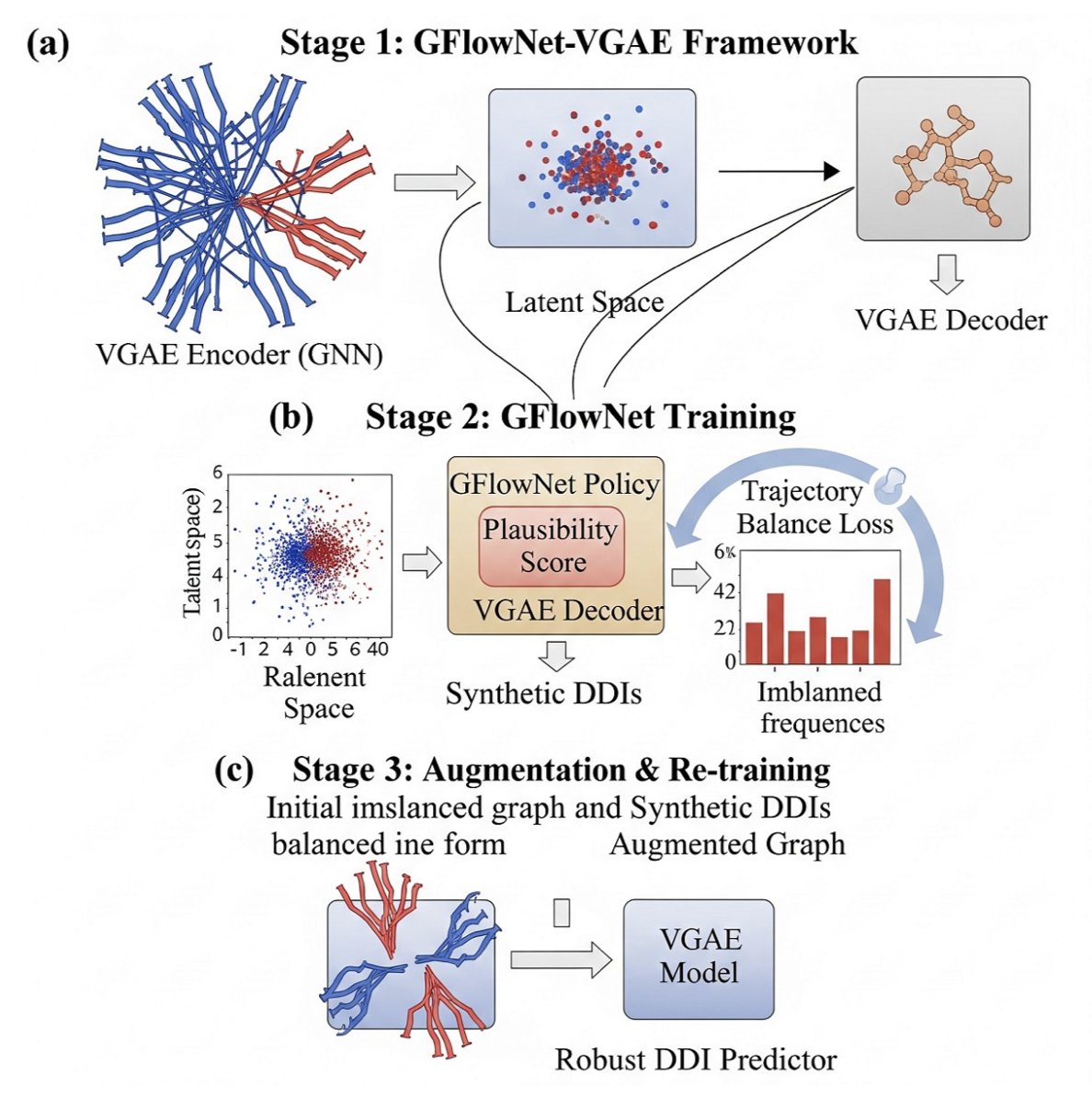

This paper from arXiv proposes a clever solution to fix the model’s skewed perspective. The core idea is not to painstakingly find more “capybara” pictures in the real world, but to use AI itself to draw thousands of realistic “fake capybara” pictures.

The “artist” they use is a generative model called Generative Flow Networks (GFlowNets).

The whole process can be broken down into three steps, like a carefully choreographed sparring match:

Phase One: Initial Training. First, they pre-train a variational graph autoencoder (VGAE) on the existing, imbalanced DDI data. The VGAE’s job is to learn how to encode each drug molecule into a “digital fingerprint” (embedding) that summarizes its chemical features. At this stage, the model learns basic drug “physiognomy,” but because the data is biased, its understanding of rare interactions is shallow.

Phase Two: Creative Practice. This is the key step. They hand the “digital fingerprints” from phase one to the GFlowNets “artist.” The task for GFlowNets is to generate new, synthetic DDI samples. But it doesn’t just draw randomly. It has a specific goal, defined by a clever “reward function.” The reward function is designed like this: the rarer the class of the DDI sample you generate, the higher your reward. It’s like telling the artist, “Stop painting cats. Paint a capybara, and I’ll pay you double!” This mechanism drives GFlowNets to constantly explore and generate samples of DDI types that are scarce in the original dataset. It must ensure not only that the generated samples look “plausible” but also that they are “rare finds.”

Phase Three: Synthesis and Mastery. Finally, they mix the high-quality “fake capybara” pictures generated by GFlowNets with all the “real cat,” “real dog,” and “real capybara” pictures from the original dataset. This creates an augmented dataset that is more balanced and diverse. Then, they use this new, richer dataset to retrain the VGAE model from the first phase. After this “remedial course,” the VGAE model is no longer the biased student who only knows cats. It gains a much deeper understanding of the rare interaction types, and its prediction performance naturally improves across the board.

The experimental results confirm this. After augmentation with GFlowNets, the dataset’s diversity metrics (like Shannon entropy) increased significantly. The final DDI prediction model showed better performance on all interaction types, especially the rare ones.

Whether we’re predicting rare diseases, genomic variants, or adverse drug events, this idea of “using AI to create data to teach AI” could become a powerful tool in our future toolkit.

📜Title: GFlowNets for Learning Better Drug-Drug Interaction Representations 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.06576