Table of Contents

- This AI model uses “positive” and “negative” guidance, like a mixologist adding desired ingredients while removing off-flavors, to design more precise and safer drug molecules.

- By learning which patient features in MRI scans respond to anti-seizure drugs, this AI model can even predict the effectiveness of new drugs it has never seen before.

- Despite the AI hype, this large-scale benchmark shows that simple, old-school chemical fingerprints still outperform nearly all new deep learning models in molecular representation.

1. ActivityDiff: AI as a Mixologist, Precisely Tuning Drug Activity

We want a molecule to have strong activity against a target we care about (like a disease-causing protein)—that’s its “efficacy.” At the same time, we don’t want it to mess with other targets, because that usually means “side effects” or “toxicity.”

In the past, doing this was a bit like playing “whack-a-mole.” You’d optimize a molecule to boost its activity against target A, but then its activity against target B would unexpectedly increase, causing unwanted side effects. So you’d modify the molecule to reduce its activity against B, but that might mess up its activity against A. The process was tedious and full of compromises.

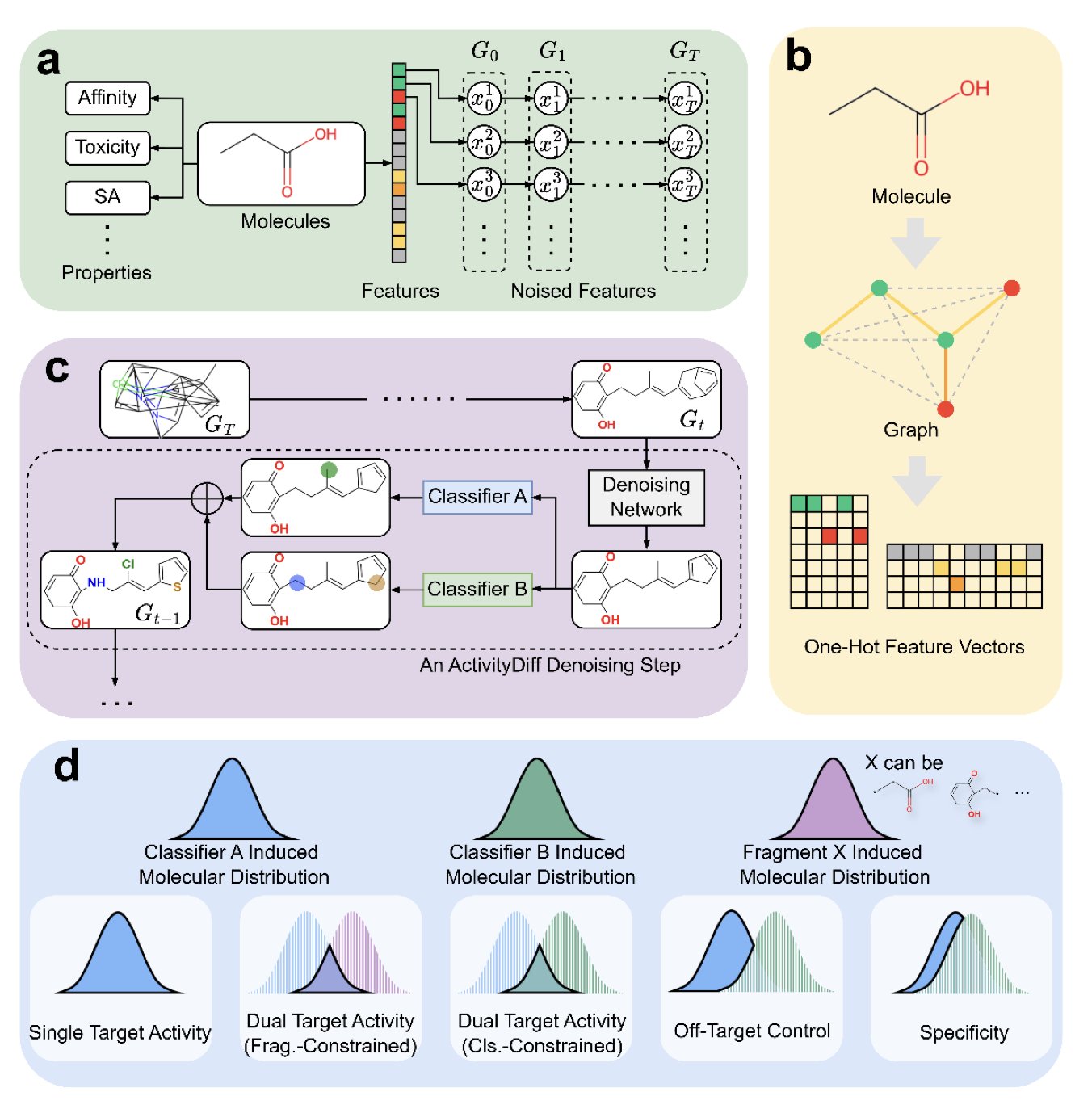

Now, diffusion models are offering a new approach. Think of a diffusion model as a skilled sculptor. You start by giving it a random lump of “clay” (a bunch of random atoms) and telling it, “I want a statue that looks like David.” It will then, step-by-step, mold that random clay into the shape you want.

ActivityDiff gives the sculptor more detailed instructions during this process. It doesn’t just say, “I want a David.” It says, “I want a David, but he must absolutely not look like a discus thrower.”

How does it do this? Through what’s called “positive guidance” and “negative guidance.”

Behind this are several small, independent AI models (drug-target classifiers) working together. You can think of them as a team of professional “art critics.”

This way, the entire molecule generation process is like searching for an optimal point in a multi-dimensional space. Positive guidance pulls it up the mountain of “high efficacy,” while negative guidance pushes it away from the cliff edge of “high toxicity.”

The best part of this method is its modularity. The “sculptor” (the diffusion model itself) can stay the same. If today you want to design a molecule that activates targets A and C but avoids target D, you don’t need to retrain the huge sculptor model. You just need to train a few new, small “art critics” (classifiers for targets A, C, and D) and combine them to guide the same sculptor. This greatly reduces computational cost and time.

The authors proved this method works. They not only successfully generated high-activity single-target and dual-target molecules but also completed more complex tasks, like “growing” a new structure onto an existing molecular fragment while ensuring the new part meets specific activity requirements. It’s like being told, “Here’s the base of a sculpture. I need you to sculpt David’s head on top, but make sure he doesn’t look like he’s about to throw a discus.”

Of course, the accuracy of the classifiers directly determines the quality of the guidance. If your “art critics” have bad judgment, they can’t offer good advice. Also, the vastness of chemical space means that the true activity of any new AI-generated molecule must ultimately be verified by wet lab experiments.

📜Title: ActivityDiff: A diffusion model with Positive and Negative Activity Guidance for De Novo Drug Design 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.06364

2. AI Reads Brain Scans to Predict Which Epilepsy Drug Works Best for You

In neurology, treating epilepsy involves a frustrating reality for doctors and patients: choosing an anti-seizure medication (ASM) is largely a process of trial and error.

We have dozens of drugs, but no reliable way to know which one will be most effective for a specific patient before starting treatment. The process becomes: try one drug, wait a few months, and if it doesn’t work or the side effects are too severe, switch to another. This is a physical and psychological ordeal for the patient.

So, any method that can reduce the cost of this trial and error is worth a serious look. This preprint paper proposes an interesting attempt: using AI to predict the effectiveness of different ASMs based only on a patient’s brain MRI scan and the radiologist’s report.

The idea itself isn’t new, but their approach has a few clever twists.

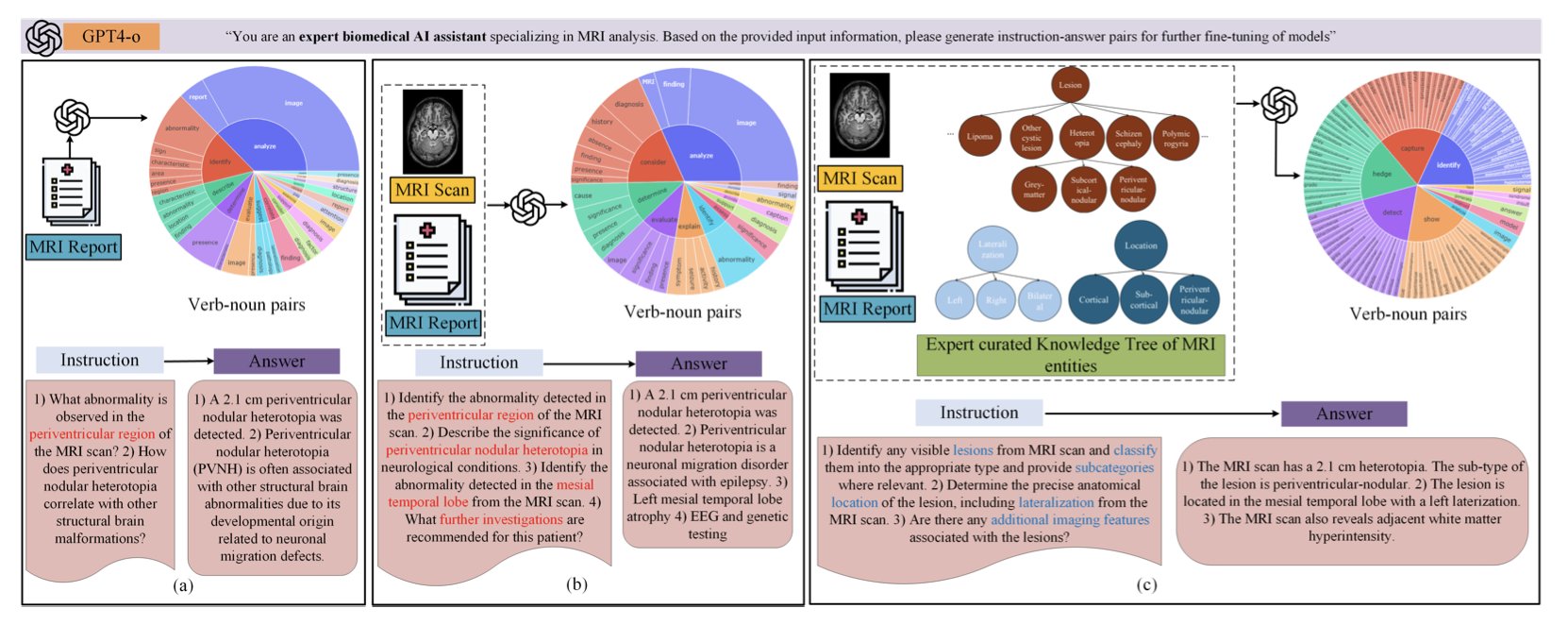

First, they didn’t use an ordinary AI model. They used a biomedical vision-language foundation model. This means the model was already trained on vast amounts of medical images and related text reports. It has an innate feel for medical terminology and imaging features, unlike a general-purpose model that would have to learn what “hippocampal sclerosis” is from scratch. It can process both pixels (MRI scans) and text (reports) and try to connect them.

Second, and this is the core innovation, is a framework called TREE-TUNE. Simply fine-tuning a model on MRI reports isn’t very effective, because the reports are full of complex information and the AI can easily get lost, latching onto irrelevant correlations. TREE-TUNE acts as an “expert navigator” for the AI. The researchers first built a “knowledge tree” of epilepsy MRI findings based on neuroscience expertise. This tree defines the hierarchy and logical relationships between various lesions, anatomical locations, and imaging features.

Then, during fine-tuning, they use this knowledge tree to “guide” the AI. As the AI reads a report, it’s prompted to identify and understand the key entities defined in the tree. This is like giving a student a textbook with detailed annotations and highlighted key points, instead of letting them browse randomly in a library. The results show that using TREE-TUNE significantly improved prediction accuracy compared to standard fine-tuning methods.

What’s really impressive is their experiment on generalizing to unseen drugs. This is a major challenge in the field. If a model can only predict outcomes for drugs it saw during training, its clinical value is limited, as new drugs are always emerging.

The team trained their model using data from only four common ASMs (like levetiracetam and lamotrigine) and patient MRIs. Then, they tested it on three other ASMs the model had never seen during training. How is this even logically possible?

My understanding is that the model likely learned something deeper than a simple mapping like “MRI image A corresponds to drug X being effective.” It probably learned a more fundamental pattern, such as “subgroups of patients with certain brain structures or pathological features (reflected in both the MRI and the report) respond better to a class of drugs with a specific mechanism of action.” Different ASMs are different molecules, but their mechanisms can overlap (e.g., both acting on sodium ion channels). So, by learning from known drugs, the model grasps this “patient feature-to-drug mechanism” relationship and then applies it to unknown drugs with similar mechanisms.

The model achieved an average AUC of 71.39% for the four drugs it was trained on, and an average AUC of 63.03% for the three unseen drugs. An AUC of 63% isn’t amazing for a clinical prediction model; it’s just a bit better than random guessing (AUC 50%).

We are still a long way from “AI-prescribed precision medicine.” But for a model to make a prediction for a drug it has never seen that is statistically better than a random guess is a remarkable proof-of-concept. It shows this path might just be viable.

This paper provides a framework. It shows that by combining multimodal data (image + text) with structured expert knowledge (the knowledge tree), AI might actually help us find the right “key” for each patient in this long and painful game of trial and error.

📜Title: Adapting Biomedical Foundation Models for Predicting Outcomes of Anti Seizure Medications 📜Paper: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.07.25333198v1

3. AI for Molecules: Old-School Fingerprints Still Beat Deep Learning

In the world of drug discovery, we’ve always been searching for a “molecular language” to communicate effectively with computers. How do you describe a three-dimensional molecule, full of electron clouds and subtle interactions, to a machine that only understands 0s and 1s, so that it can grasp the molecule’s “personality” and predict what it will do in the human body? This is a core problem that has puzzled cheminformatics for decades.

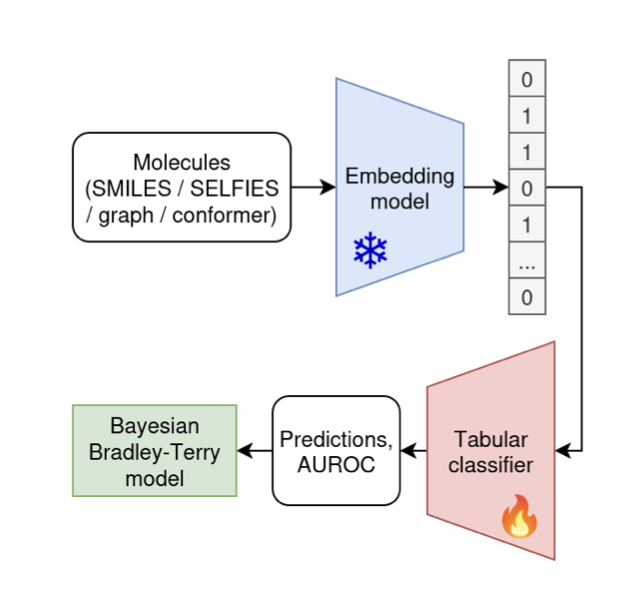

In recent years, with the wave of deep learning, the answer seemed obvious: use massive neural network models pretrained on millions or even billions of molecules. These models, like “PhD students” who have read the entire chemical literature, should in theory understand the “grammar” and “semantics” of molecules far more deeply than any old method, generating a more universal and powerful molecular representation (embedding).

Sounds great, right? The question is, is it true?

This new paper from arXiv did the dirty work: they organized a large-scale “cage match.” They brought in 25 of these “AI PhDs” (pretrained models) and had them compete against an “old-school craftsman” (the traditional ECFP molecular fingerprint method) across 25 different “arenas” (datasets).

What is ECFP? You can think of it as a way to take a “snapshot” of a molecule. It doesn’t care about the molecule’s deep grammar; it just bluntly lists the various local chemical environments and atomic fragments present in the molecule. It’s like describing a person not by writing a biography, but by listing a series of tags: “wears glasses, has a beard, wears a blue shirt, is 180cm tall.” The method is simple, fast, and has been around for years.

The results might be a bit awkward for many people.

When the smoke cleared, the “old-school craftsman,” ECFP, was left standing almost unscathed in the center of the ring, surrounded by a floor of fallen “AI PhDs.” The data showed that across the 25 different tasks, nearly all the fancy, complex neural network models showed “little to no improvement” over the simple ECFP.

It’s like you hired a Michelin three-star chef to make you scrambled eggs, only to find they don’t taste as good as the ones from the 30-year veteran at the corner breakfast joint.

Of course, there are always exceptions. In this matchup, one model called CLAMP did consistently outperform ECFP. Perhaps the road to better molecular representations isn’t completely blocked. But it also highlights just how mediocre the performance of the other twenty-plus models was.

So, what does this mean?

First, it’s a humbling result. It reminds us that in a complex field like cheminformatics, we shouldn’t be easily fooled by a model’s complexity or the size of its training data. Just because a model has “seen” more molecules doesn’t mean it truly “understands” them.

Second, for all the computational chemists and data scientists on the front lines of drug discovery, this is a very practical lesson. Before you try any new, cool-sounding molecular representation model, please, please run ECFP as a baseline first. If your new model can’t even beat ECFP, you are likely just wasting precious computational resources and time chasing an illusion of being “advanced.”

This paper isn’t a death sentence for deep learning in molecular representation. It’s more like a precise “health check-up” that points out our current weaknesses. Future breakthroughs may not come from building bigger, more general models, but from finding cleverer ways to integrate more chemistry and biology knowledge into the model’s design—much like what CLAMP might have done.

📜Title: Benchmarking Pretrained Molecular Embedding Models For Molecular Representation Learning 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.06199v1