Contents

- The best thing about BOLD-GPCRs is that it doesn’t just predict small molecule activity; it can also tell you how mutations on the protein will change its function. This is invaluable for tackling GPCR targets.

- AttriLens-Mol uses reinforcement learning to give AI “chemist goggles,” forcing it to identify key molecular features before making a prediction. This makes the results not just accurate, but also explainable.

- An AI drug design “dream team” performs astonishingly well when aggressively pursuing a single objective, but it does so at the cost of drug-likeness, exposing the conflict between a team of specialists and a versatile generalist.

1. AI Unlocks GPCRs: Predicting Mutations to Guide Drug Development

GPCRs, Class A GPCRs. For drug developers, these letters represent over half of all marketed drugs, and also a source of endless frustration. These proteins are like soft strands of spaghetti embedded in the cell membrane. They have a wide range of conformations and engage in complex behaviors like “biased agonism,” which makes studying them even harder.

Most AI prediction models available today work like this: you input a molecule, and it spits out an activity value. That’s useful, of course, but for GPCRs, it’s far from enough. That’s because a GPCR’s function and its response to a drug are closely tied to its own sequence, especially to mutations in single amino acids. Many diseases are caused by just one point mutation on a GPCR.

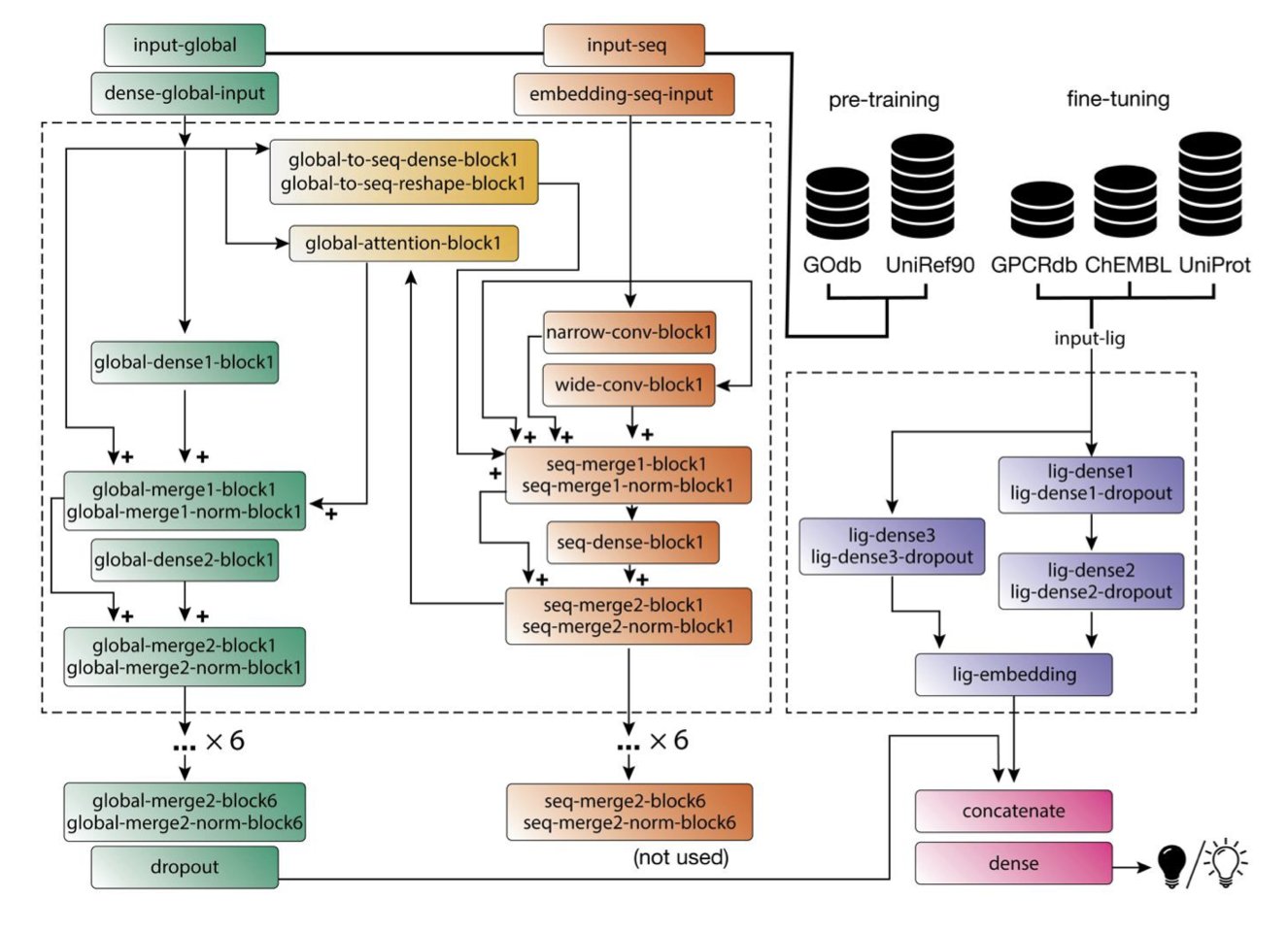

The clever part about BOLD-GPCRs is that it places both variables—the protein and the ligand—at the core of the model.

Here’s the method it uses:

- Reading the protein: It uses a Transformer model called ProteinBERT to process the GPCR sequence. This is different from models that treat amino acids as isolated letters. A Transformer understands context; it knows how a residue’s position and its neighbors in the sequence affect its function. It is “reading” the language of the protein.

- Understanding the small molecule: For the ligand, it doesn’t do anything fancy. Instead, it uses classic physicochemical property embeddings. This is like creating a precise “chemical ID card” for the molecule, describing its size, shape, charge distribution, and so on.

Then, it fuses these two pieces of information for training. It’s like having a top structural biologist (who understands proteins) and an experienced medicinal chemist (who understands small molecules) sit down for a meeting, rather than talking past each other.

This design brings two benefits.

First, it can predict the effect of a specific mutation on a drug’s activity. What does this mean for us? We can ask the computer directly: “If a patient’s GPCR has this mutation, will my drug candidate still work? Will its activity get stronger or weaker?” This is a powerful tool for developing precision medicines tailored to patients with specific genotypes.

Second is its explainability. Through the model’s “attention mechanism,” we can see which parts of the protein the AI is “looking at” when it makes a prediction. If it focuses heavily on known key activation residues when predicting an agonist’s activity, our confidence in that prediction increases. For a medicinal chemist, this is like getting a “heat map” of the target’s binding pocket, guiding the next steps in modifying the molecule’s structure.

Of course, this is still a computational model, and all predictions must ultimately be validated in a wet lab. And the model does not yet integrate 3D structural information, which is clearly an important area for future improvement.

📜Title: BOLD-GPCRs: A Transformer-Powered App for Predicting Ligand Bioactivity and Mutational Effects Across Class A GPCRs 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.08.04.668547v1

2. Making AI Stop Guessing: Teaching It to Think Like a Chemist

What’s the biggest headache when dealing with AI models? Their “black box” nature. One model tells you a molecule’s solubility is -3.5, another says -4.2. Who’s right? Why? Who knows. They’re like fortune tellers who give you a prophecy but never explain the signs. You use them, but you never feel completely sure.

This paper on AttriLens-Mol is designed to solve this core problem: before letting an AI give you a result, force it to “show its reasoning.”

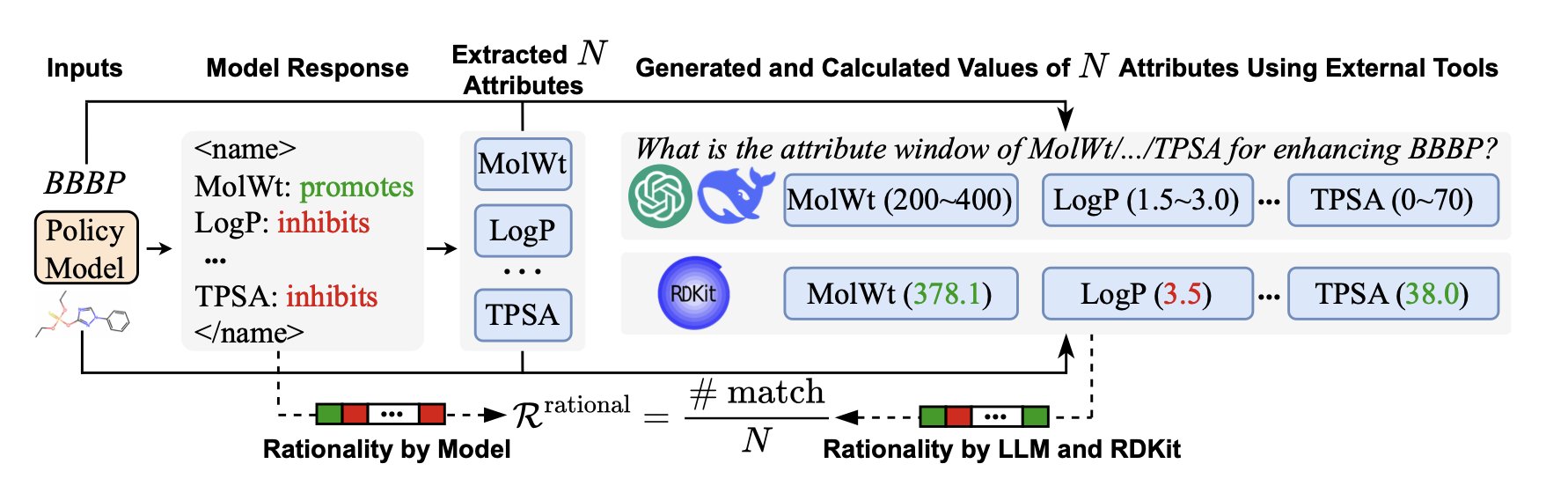

The essence of this framework is “attribute-guided reinforcement learning.” You can’t just give me a number; you first have to tell me which functional groups or structural fragments in the molecule led you to that conclusion. For example, when predicting a molecule’s water solubility, the AI must first learn to identify how many hydroxyl or carboxyl groups are present, or whether there’s a large, greasy aromatic ring.

This sounds great, but how is it done?

It relies on a reward mechanism in reinforcement learning:

- Format and length rewards: This is the foundation. It requires the AI’s answer to be structured and to the point, not long-winded.

- Rationality Reward: This is the brilliant part. After the AI proposes a molecular feature it thinks is relevant, the system immediately “calls in an expert” for cross-validation. This expert could be an established cheminformatics tool like RDKit or a more powerful “teacher” model like GPT-4o. If the feature the AI mentions aligns with chemical common sense, it gets a reward. If it starts talking nonsense, like calling an alkane hydrophilic, it gets penalized.

It’s like training a junior chemist. You don’t just check if their experiment was successful; you also listen to them explain why they did what they did. If they can articulate a clear and logical reason, then they’ve truly learned.

The results were surprisingly good. A “small” model with only 7 billion parameters (like Qwen2.5 or LLaMA3.1), after being trained with AttriLens-Mol, could perform on par with giants like GPT-4o and DeepSeek-R1 on molecular property prediction tasks. On some datasets, it even outperformed them. This is great news for labs that don’t have an unlimited budget for computing resources.

More importantly, we get the “explainability” we’ve been looking for. The AI’s output isn’t just a prediction value; it comes with a “reasoning report.” We can see clearly that the AI made its judgment because it noticed a specific fragment in the molecule. The researchers even fed the features extracted by the AI into a simple decision tree model and found they performed much better than features generated by traditional methods.

📜Title: AttriLens-Mol: Attribute Guided Reinforcement Learning for Molecular Property Prediction with Large Language Models 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.04748v1

3. AI Teams for Drug Discovery: Strength in Numbers or Too Many Cooks?

This paper explores a question: how can we organize and manage these AIs to work like an efficient R&D team?

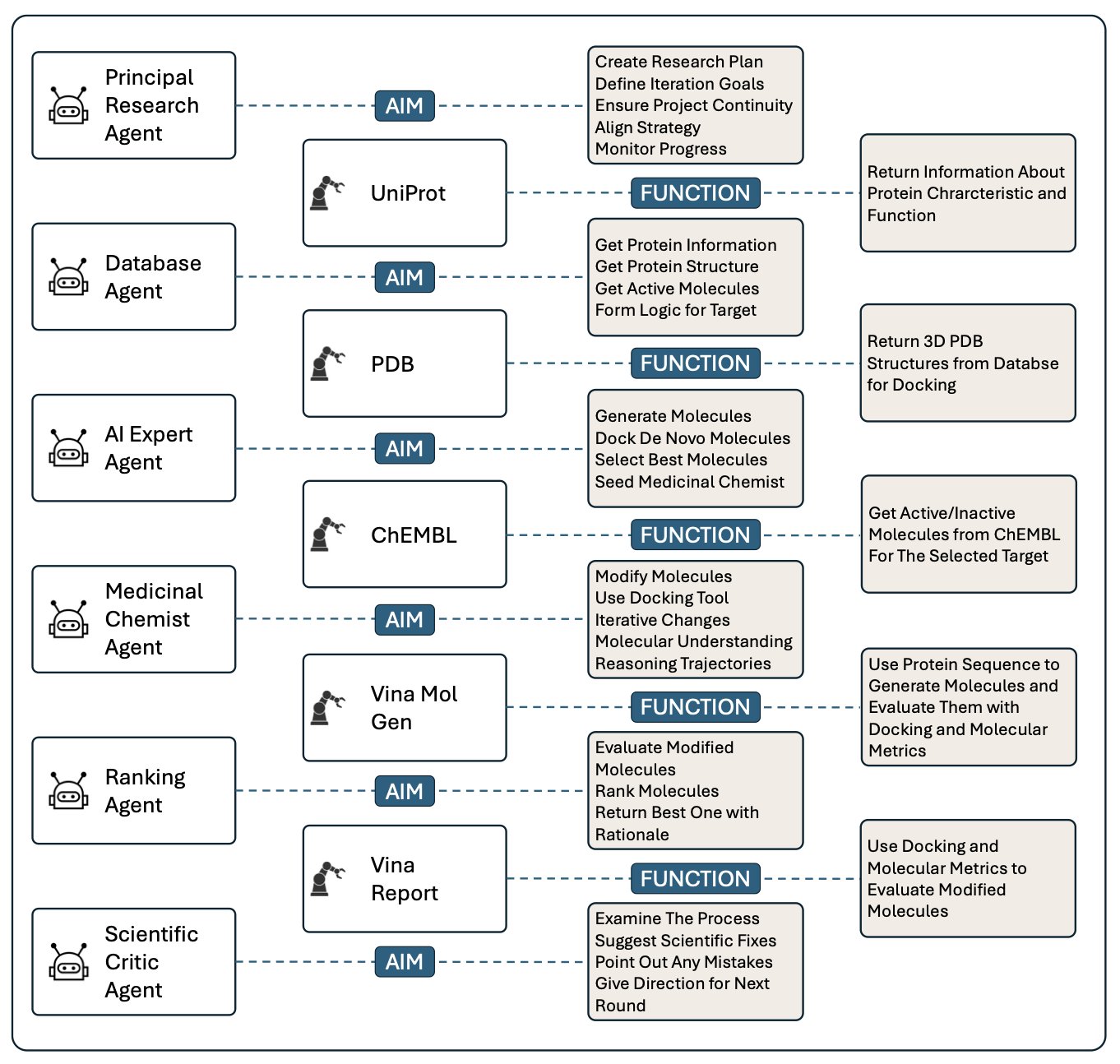

The researchers built a rather impressive “AI committee.” It includes: * Principal Researcher: The project manager, responsible for overall coordination. * Database Agent: Responsible for digging up information from literature databases. * AI Expert: Plays with various generative models to come up with ideas. * Medicinal Chemist: Just like us, stares at molecular structures and assesses feasibility. * Ranking Agent: Responsible for scoring and ranking candidate molecules. * Scientific Critic: The devil’s advocate, responsible for finding flaws and raising questions.

Isn’t this just like our daily project meetings? Except this time, none of the participants are human.

They used this system to tackle the old target AKT1. The result? The “AI dream team” was indeed powerful. Compared to a single AI working alone, it boosted the predicted binding affinity by a solid 31%. This shows that breaking down a complex task and assigning different parts to specialized agents can push performance on one specific metric to the extreme.

But here comes the twist, and it’s the most interesting part of this work. When the researchers examined the molecules optimized by the team, they found that while the “dream team’s” creations had strong binding affinity, their overall drug-likeness was actually worse than the molecules generated by the “lone wolf” single agent.

This is a perfect replica of a common scenario in drug discovery. The chemist working on structure-activity relationships pushes hard to increase activity, only for the colleague in ADMET to jump in and say, “This molecule’s solubility is as bad as a brick; it’ll never be a drug!” This AI system perfectly exposes the dilemma where local optimization does not equal global optimization.

The multi-agent team is like a group of specialists. Each one wants to score 100% in their own field, but the result is a “Frankenstein’s monster” of a molecule. The single agent, on the other hand, is like an experienced old chemist who constantly balances activity, solubility, and metabolic stability.

The greatest value of this system might not be that 31% improvement, but its “auditable” design. The system records all the “conversations” and decision-making processes between the agents. This is so important. We no longer have to make a wish to an AI “black box.” We can review the entire design process like reading project meeting minutes: Which wild idea did the AI expert propose? On what grounds did the medicinal chemist agent reject it? This feature transforms AI from a guessing game into a scientific tool that is understandable, trustworthy, and verifiable.

This system still needs to evolve. The next step is to equip it with more “weapons,” like tools for predicting ADMET and selectivity.

📜Title: An Auditable Agent Platform for Automated Molecular Optimisation 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.03444