Table of Contents

- By forcing a model to play a “protein sequence puzzle” game, researchers developed an efficient pre-training method that shows impressive potential in “double-blind” predictions for brand-new drugs and targets.

- The smartest thing about this AI model isn’t its predictions. It’s that during training, it’s forced to respect the “common sense” of chemistry and biology, allowing it to accurately find rare “active” signals in a vast sea of “inactive” data.

- General-purpose large models are all show in specialized fields. To make AI truly useful in pharmacy, you have to feed it high-quality, specialized databases using a RAG architecture.

1. Protein Sequence Puzzles: A New Way for AI to Predict Drug Targets

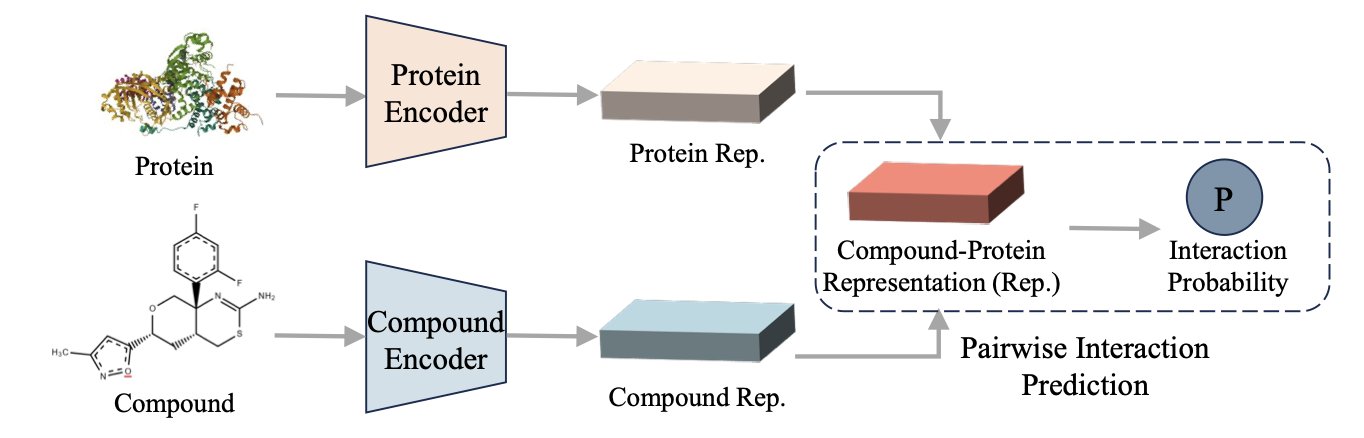

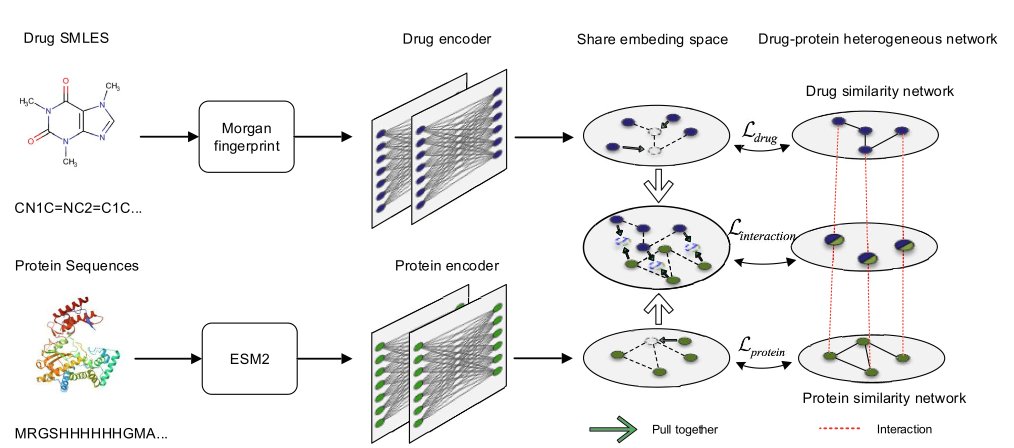

Every day, we face a massive number of possibilities. On one side, countless chemical compounds. On the other, a seemingly endless list of potential protein targets. How do you find the right match in this haystack? AI has given us a lot of hope over the years, but it’s also produced a lot of “black box” models. Everyone is competing on data volume and model size, but this paper offers a different approach.

The PSRP-CPI model proposed by these researchers isn’t about how much data you feed it, but how you teach it. They designed a clever pre-training game: subsequence reordering.

Think of it as teaching a machine to understand protein “grammar.” Instead of just having it read amino acid by amino acid, you take a full protein sequence (a sentence), chop it into several pieces, shuffle them, and then ask the model to put them back in the original order. It sounds simple, but to do it, the model has to understand which fragments are likely to be near each other in 3D space and which ones work together functionally, even if they’re far apart in the sequence. This is exactly what drug developers think about all day: allosteric sites and long-range regulation. This method forces the model to learn the long-range dependencies within a protein, not just memorize local information like “B usually follows A.”

Where does this power show up? In the toughest test case: zero-shot learning.

This is especially true for the “Unseen-Both” scenario, where both the compound and the protein are complete strangers the model has never seen during training. This perfectly mimics our real-world challenge of exploring new targets or new chemical scaffolds. Most models are just guessing in this situation, but PSRP-CPI’s performance is exceptional. Its AUROC and AUPRC scores, two key metrics, leave competitors behind.

The paper’s data shows that it can be trained on a much smaller dataset than large models like ESM-2 or ProtBert and still achieve better results on downstream compound-protein interaction (CPI) prediction tasks. In an era where compute is money, what that means is obvious. It tells us that a smart learning strategy can sometimes be more important than just throwing more computing power at a problem.

Of course, an in silico prediction is a long way from a real drug. A high-scoring pair from the algorithm might not be a match in a wet lab experiment. But as a filtering tool before high-throughput screening, this “sequence puzzle” approach is undoubtedly efficient and clever. It suggests the model might actually be learning some underlying logic about protein folding and function, rather than just doing advanced pattern matching. The next step is to see how its predicted “new combinations” perform in a test tube. If it can help us find a few promising lead compounds that traditional methods missed, its value would be significant.

📜Title: Zero-Shot Learning with Subsequence Reordering Pretraining for Compound-Protein Interaction 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.20925

3. To Be Useful, AI in Pharmacy Needs to Be Fed Expert Data via RAG

Everyone is praising the versatility of general-purpose large models, as if AI will be writing prescriptions tomorrow. But in a clinical setting where lives are on the line, would you really trust a “jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none” to make decisions? This new paper gives us an important warning and points to a clear path forward.

Pharmacogenomics (PGx) is an extremely complex field, involving genetics, pharmacology, and clinical practice. The related guidelines (like CPIC) are numerous and dense, and a small mistake can lead to errors. Asking a general-purpose Large Language Model (LLM), raised on the ocean of internet information, to handle these issues is like asking a well-read history professor to fix your car engine. He might be able to discuss the history of the internal combustion engine with you, but he definitely won’t understand why your car is making a rattling noise. The result is the model confidently stating false information, which is what we call a “hallucination.”

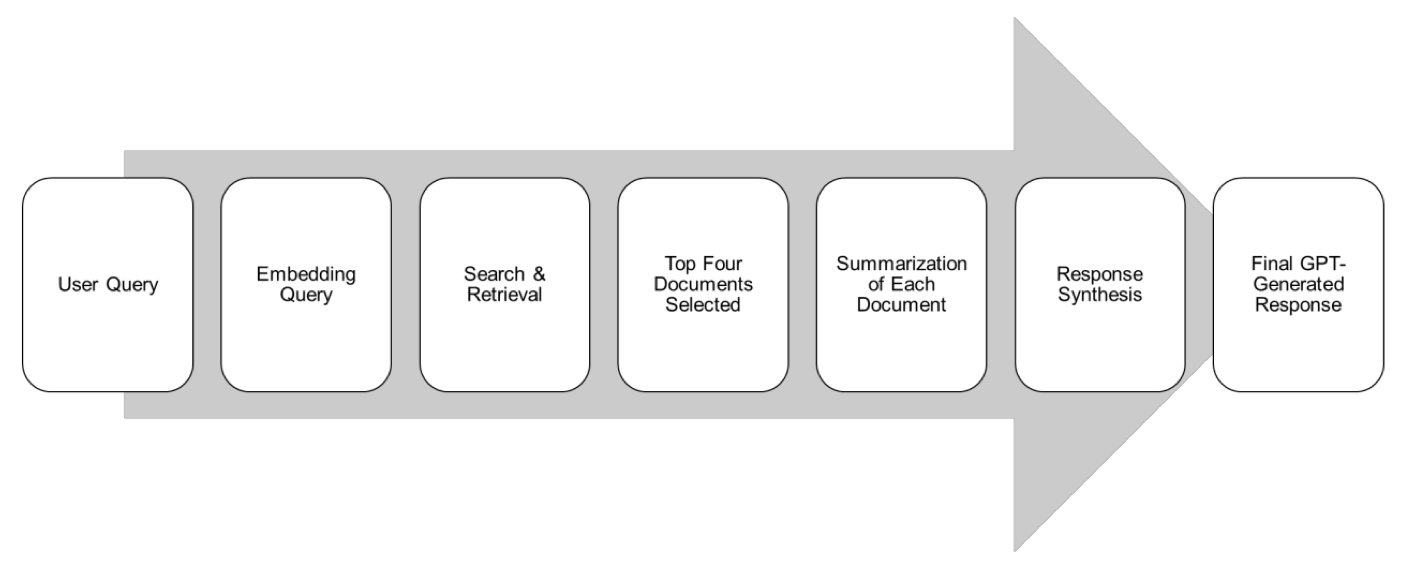

The authors of this study were clear-headed. They didn’t try to build a “god of pharmacy” model from scratch. Instead, they took a smarter approach: Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG).

RAG is basically an open-book exam for a large model. When you ask it a question, it doesn’t just guess based on its vast but mixed-quality memory. It first looks up the most relevant chapters in designated, authoritative textbooks (in this case, the CPIC and PharmGKB gold-standard databases). Then it organizes and summarizes what it finds before giving you an answer. This way, the answers have a clear, traceable source, and the chance of it talking nonsense is much lower.

The researchers used this method to build an AI assistant called Sherpa Rx. They then designed 260 realistic pharmacogenomics questions for a head-to-head comparison. And the result?

In accuracy (4.9/5) and completeness (4.8/5), Sherpa Rx, “fed” with a specialized knowledge base, completely outperformed the well-known general-purpose model, ChatGPT-4o mini.

This is more than just a win in numbers. It proves a point that people in the industry have known for a while: in serious scientific and medical fields, the quality of data is far more important than the quantity. Training a model on all the noise of the entire internet is less effective than using a small but rigorously validated, gold-standard dataset for retrieval augmentation.

Of course, this doesn’t mean we can start using it in clinics tomorrow. The study’s sample size is small, and the 260 test questions were designed by the researchers themselves, which could introduce bias. The real test will be to throw it into a chaotic, noisy, real-world clinical environment and see if it can handle the variety of strange questions doctors ask, all while consistently providing reliable advice.

📜Title: Validating Pharmacogenomics Generative Artificial Intelligence Query Prompts Using Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.21453