Table of Contents

- Diffusion models are taking molecular generation into the third dimension. AI is no longer just a “graphic designer” drawing chemical diagrams but a “3D sculptor” creating directly inside the target site.

- A new benchmark shows that top Large Language Models can generate bioinformatics analysis code on par with, or even better than, top human competition teams. The era of automated research may be closer than we think.

- The Tripleknock AI model brute-forces the lethal effects of three-gene combinations, bypassing the speed bottlenecks of traditional metabolic models and opening a new fast lane for finding multi-target antibiotics.

- This paper outlines a grand vision: using AI to build a “programmable virtual human” that can simulate the entire journey of a drug from molecule to human body, trying to solve the translational problem in drug discovery from the ground up.

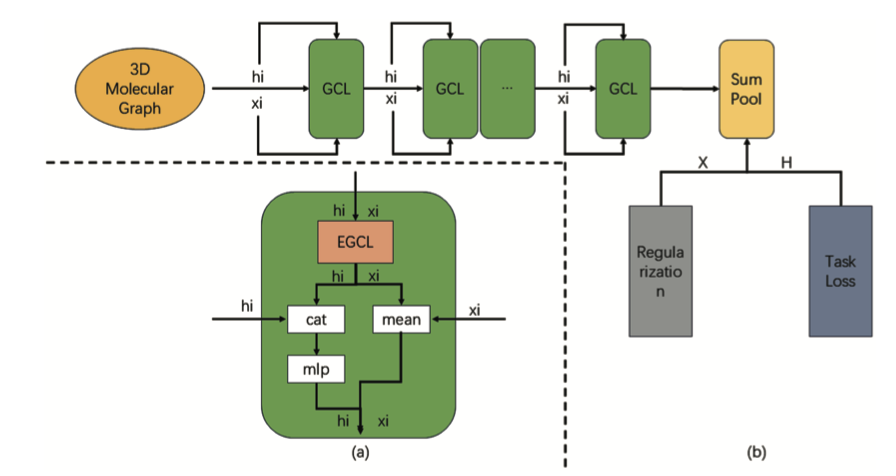

- PairReg introduces a clever regularization method that effectively mitigates the oversmoothing problem in deeper EGNN models, helping AI get a clearer view in molecular simulations.

1. Diffusion Models: AI Drug Discovery, From 2D Doodles to 3D Sculptures

If you’re in drug discovery right now and haven’t heard of Diffusion Models, you must be doing experiments in a cave. The hype is almost at CRISPR levels. Every day, a new paper claims to have generated some amazing molecule with one. But honestly, most of us are just nodding along.

This review paper acts like an experienced guide, drawing us a map of this new continent called “AI molecular generation.”

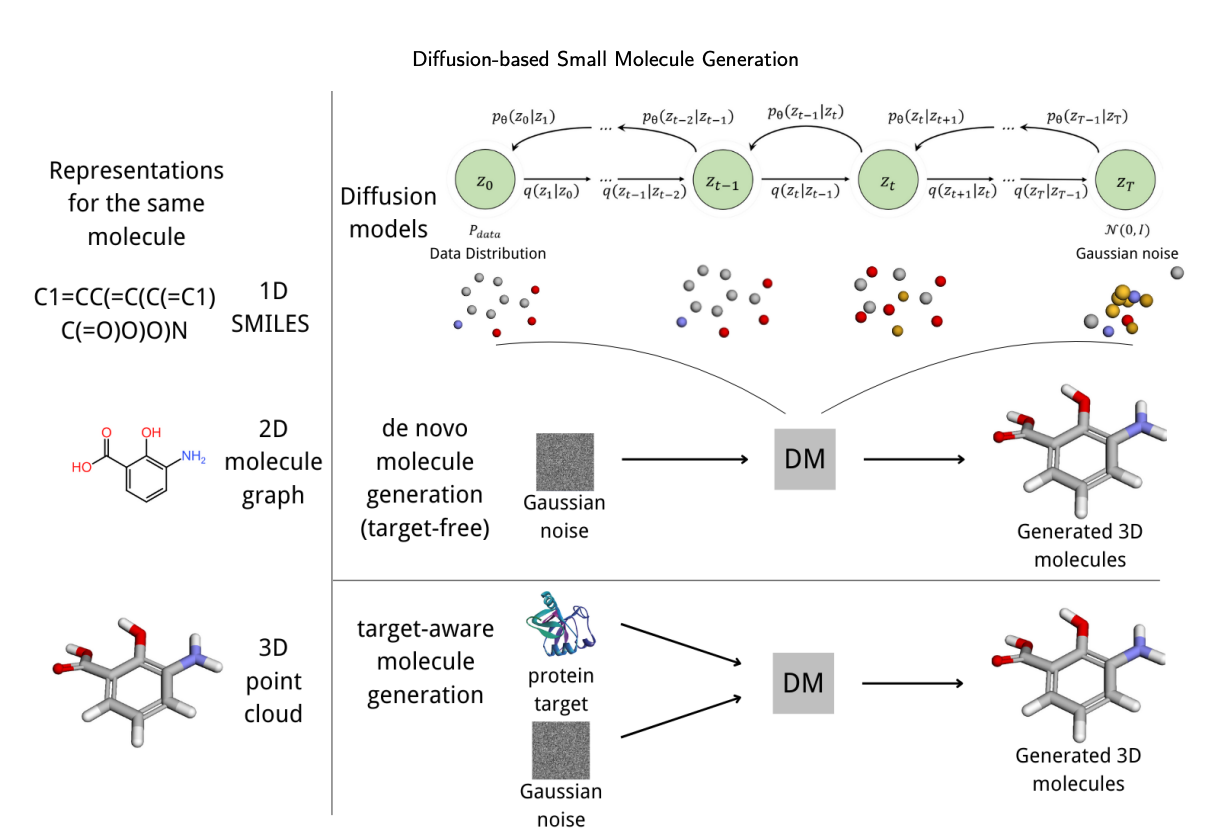

So what exactly is a diffusion model?

You can think of it as a “molecular sculptor.” It starts with a random cloud of “atomic noise” (like a rough block of marble) and then carefully chips away the noise, step by step, until a clear, valid molecular structure emerges. This process is naturally suited for handling 3D spatial information.

Why is this important?

Because many of our past AI models thought in “2D.” They generated SMILES strings (1D) or molecular graphs (2D). That’s like getting a blueprint for a car instead of a working model. But drug discovery is fundamentally a 3D problem—a 3D molecule has to fit into a 3D target pocket.

Diffusion models, especially those with “SE(3) equivariance,” are designed to solve this. That fancy term, translated into plain English, means the model understands physics. It knows that if you rotate or move a molecule, it’s still the same molecule and its chemical properties don’t change. This ensures the 3D structures it generates are physically plausible, not some horrifying “Cthulhu” creations.

This review also provides a useful classification, dividing these models into two main camps: 1. Target-free: This type of AI is like a free-spirited explorer. Its goal is to navigate the vast chemical universe and discover new and interesting chemical scaffolds. 2. Target-aware: This AI is a focused locksmith. You give it a specific target pocket (the lock), and its job is to design the key (the ligand) that fits perfectly.

Of course, the review is also honest about the current challenges. For instance, generating a large molecule is still computationally expensive. And the step-by-step “denoising” process can lead to an accumulation of errors.

But this review is an invaluable guide. It shows us that diffusion models aren’t just another tech gimmick. They represent a fundamental shift—from drawing molecules to building them. For people who work with molecules every day, that’s exciting.

📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.08005

2. AI Writes Research Code Better Than Top Humans?

In bioinformatics, the DREAM challenges are the Olympics. The world’s sharpest minds come together to tackle the toughest, most realistic biomedical data, competing to build the most accurate predictive models. The winning teams’ code is usually a product of brilliance and hard work.

Now, someone has asked an interesting question: what happens if we let an AI take this test?

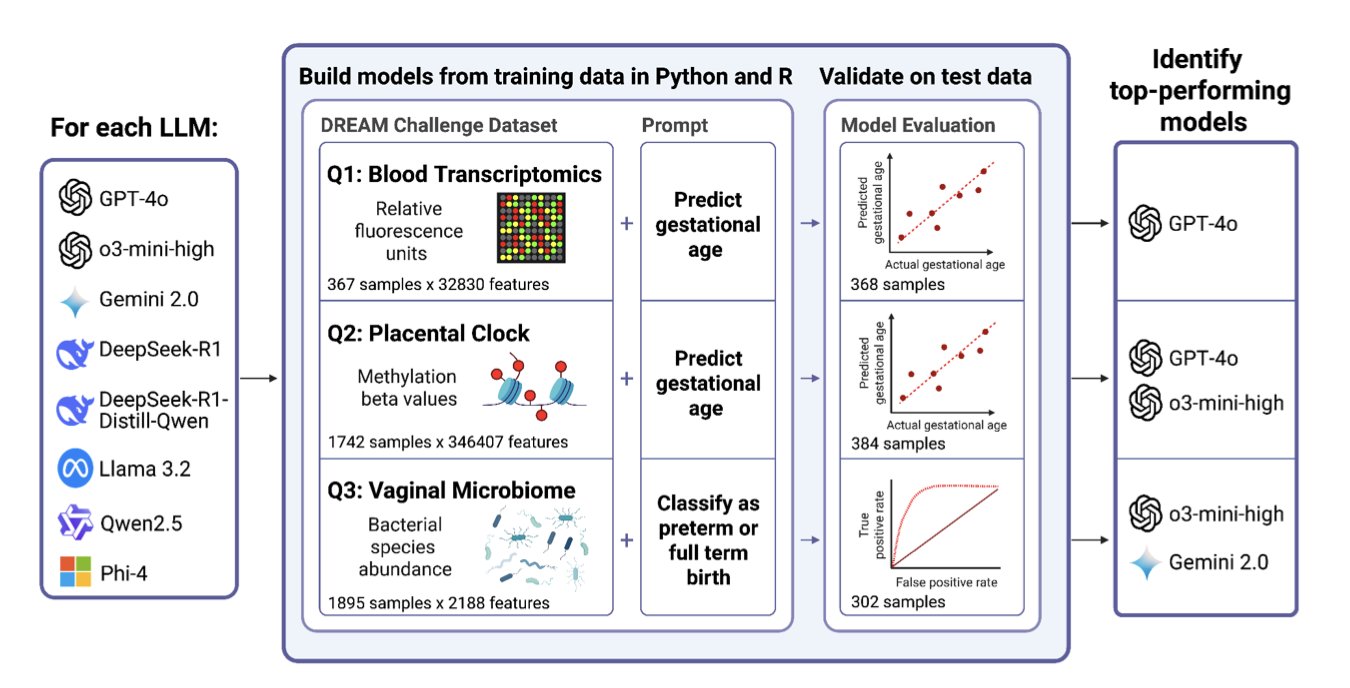

Researchers took classic datasets from DREAM challenges in reproductive health—like predicting gestational age from gene expression or preterm birth from microbiome data—and gave them to eight popular Large Language Models (LLMs), including those from OpenAI, Google, and some open-source ones.

The test was simple: no cheating, just use natural language prompts to get the LLMs to generate working R or Python code for the analysis tasks.

The results are a little chilling.

The top performer, OpenAI’s GPT-4o-mini, successfully completed 7 out of 8 tasks. More importantly, the results from its generated code were competitive with the original human champion teams, and in some cases, even slightly better. This wasn’t asking an AI to write a poem about ribosomes; this was asking it to write award-winning, functional code for a notoriously difficult bioinformatics problem.

One particularly interesting finding was the “exceptional performance” of R. The success rate for LLMs generating R code was more than double that of Python.

Why? It’s not that LLMs have a natural preference for R. The real reason is the ecosystem.

R’s Bioconductor project provides an incredibly powerful and standardized arsenal of tools for genomics and other omics data. These packages have consistent interfaces and thorough documentation, making them almost tailor-made for an AI to learn from and use. Python, while powerful, has a more fragmented toolchain in this specific domain. This is an important reminder for us: the standardization and usability of tools will become more important than ever in the age of AI.

What does this mean?

First, it signals a change in how we work. In the past, a complex omics data analysis project might have taken a dedicated bioinformatician weeks. Now, a wet-lab biologist might be able to complete a preliminary exploratory analysis in an afternoon with a few “conversations” with an LLM. The efficiency gap is huge.

Second, it could solve a long-standing problem in open science: reproducibility. We’ve all downloaded code from GitHub that simply refuses to run. LLMs can generate standardized, executable analysis pipelines, which could make verifying and replicating research results much easier.

Of course, these tools aren’t perfect yet. Some models in the test failed completely, and even the best one had its misses. But the direction is clear. The AI intern that can process your data and write your analysis scripts has arrived. We should start learning how to work with it now.

📜Title: Benchmarking Large Language Models for Predictive Modeling in Biomedical Research With a Focus on Reproductive Health 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.07.663529v1 💻Code: https://github.com/vtarca7/LLMDream

3. Tripleknock: AI Precisely Snipes Three Bacterial Targets at Once

The state of antibiotic development is bleak. We develop a single-target drug, and bacteria evolve resistance in no time, as if mocking our efforts. The consensus in the field is that we need a multi-pronged approach, a “combination punch”—multi-target drugs—to overwhelm bacteria.

It’s a great idea, but the reality is tough.

Finding combinations of two targets is hard enough. Three targets is a combinatorial nightmare. Trying every possibility in the lab? You might not even screen one species by the time you retire.

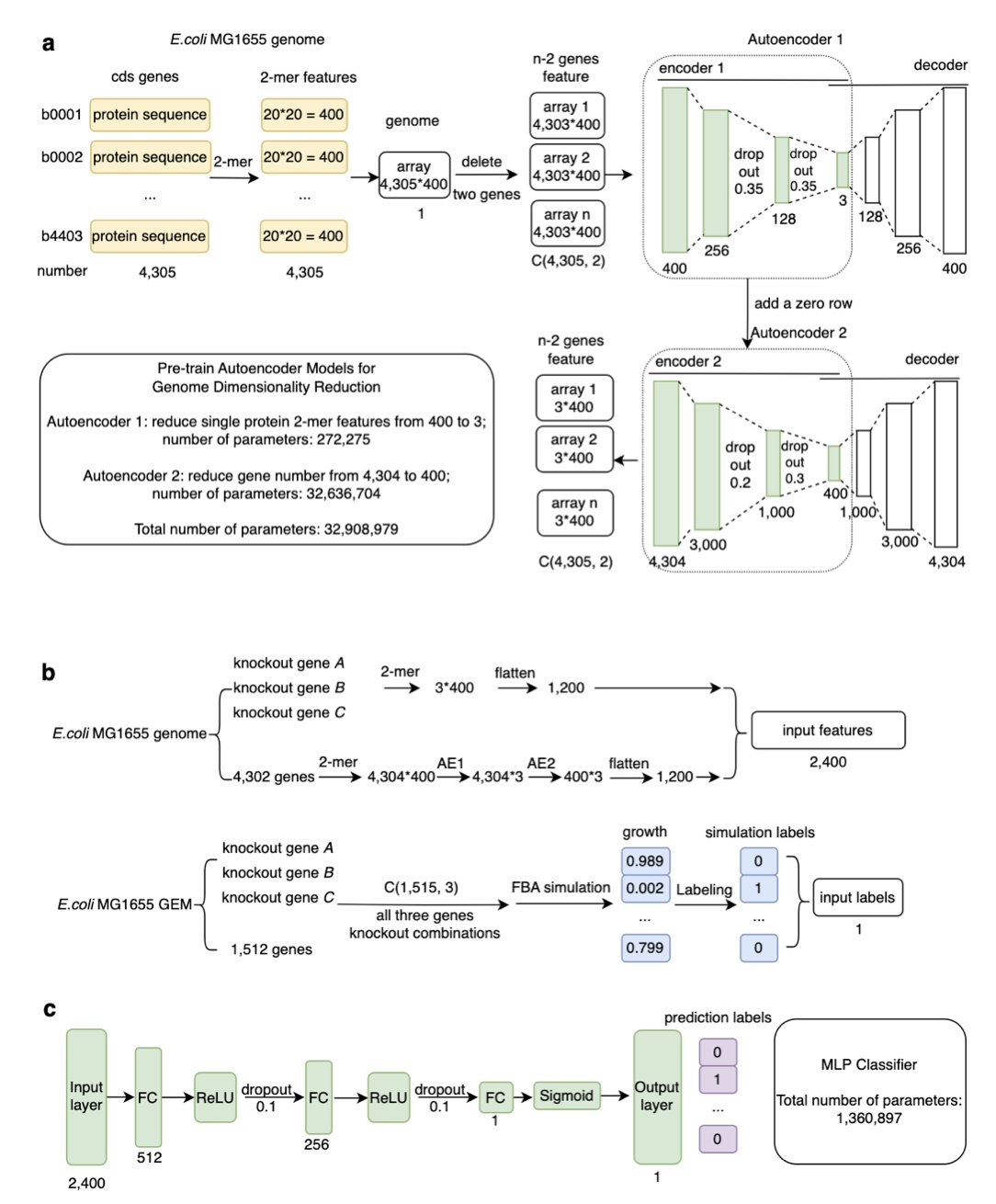

Tripleknock predicts whether bacteria live or die when three genes are knocked out simultaneously.

The researchers didn’t use slow, clunky genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). Using GEMs for this is like navigating with an old hand-drawn map; it has a lot of detail, but it’s painfully slow. Tripleknock takes a different route. It uses an autoencoder to compress the massive amount of whole-genome data by nearly 1000 times—think of it as a “super zip file” for the genome. Then, a simple multilayer perceptron (MLP) identifies “lethal patterns” within this compressed data. The whole process doesn’t care about the specifics of metabolic pathways; it only cares about whether “this combination looks like it will kill the bacteria.” It’s simple, brute-force, and effective.

The results are quite good. The model was trained on E. coli K-12 and then tested on six other pathogenic species of Enterobacteriaceae. The average F1 score for cross-species prediction was 0.77. That number isn’t perfect, but for a problem of this hellish complexity, achieving nearly 80% accuracy is a remarkable start. It’s like sending out a scout who is 77% sure about which three directions to attack from to take out the enemy’s base. I would take that intelligence.

Even more important is the speed. It’s a full 20 times faster than traditional flux balance analysis (FBA). This means calculations that used to take days or weeks can now be done in a few hours. In the race against time that is drug development, time is money, and it’s also lives.

The model isn’t a silver bullet. The researchers themselves admit that its ability to generalize is directly linked to how clearly the features can be separated. In other words, if the lethal signal is buried in the genomic background noise, the AI will also get confused. This points to a deeper scientific question: the lethal effect of genes depends not just on the ones you knock out, but also on the chain reaction their absence triggers across the entire complex genomic network.

So, Tripleknock is more like a powerful probe that helps us peek into that mysterious “gene-genome” interaction network. It dramatically narrows our search space, allowing our wet-lab colleagues to focus their precious resources on the few most promising target combinations.

📜Title: Tripleknock: Predicting Lethal Effect of Three-Gene Knockout in Bacteria by Deep Learning 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.31.667916v1 💻Code: https://github.com/Peneapple/Tripleknock

4. The AI Virtual Human: The Ultimate Simulator for Drug Development?

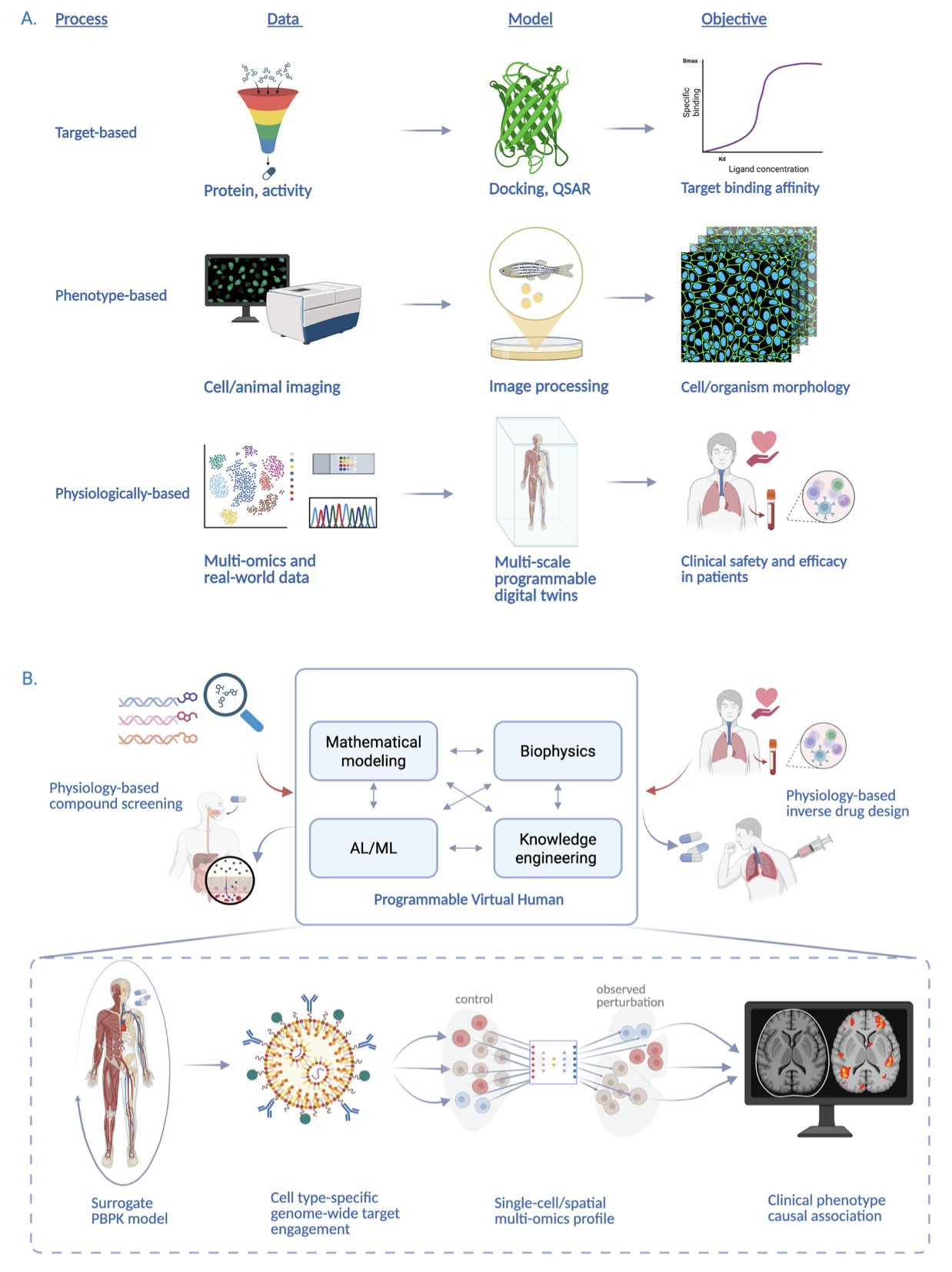

Let’s be honest, we’ve all seen countless presentations on AI in pharma, usually about discovering a new target or designing a new molecule. It’s getting a bit old. This paper on “Programmable Virtual Humans” (PVH), however, has ambitions on a whole new level.

What is the researchers’ goal? They aren’t satisfied with small-scale explorations at the molecular level. They want to create a “person” in a computer—a virtual physiological system that can simulate the entire process of a drug, from injection into the body to its final phenotypic effect. This is like the ultimate version of The Sims for drug development, or more accurately, a “flight simulator” for pharmacology.

What’s the biggest pain point in drug development? The “translational gap.” A molecule looks great in cell assays, works miracles in mice, but then fails in human clinical trials, either by doing nothing or by being toxic. Countless hours and dollars go down the drain. This paper’s core idea is a direct assault on the industry’s biggest problem.

Their approach is interesting. We’ve been using traditional physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) models for decades. They’re useful, but they’re like old maps, only showing a rough outline. Now, the researchers plan to completely overhaul them with new weapons like Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). The beauty of PINNs is that they aren’t pure black boxes. While learning patterns from data, they are also “taught” the basic laws of biology and physics. This is like a student who not only crams for exams but also understands the underlying principles, leading to much more accurate predictions.

They also plan to integrate single-cell and spatial omics data. What does this mean? We’ll no longer be looking at a drug’s effect on the “liver” in general. We could potentially see exactly how it affects hepatocytes and Kupffer cells within the liver, and how these cells “talk” to each other. This level of resolution could elevate our understanding of drug mechanisms and potential off-target effects to a new dimension. Imagine being able to see in a virtual human which cell types in which tissues a drug might cause trouble in, all before you give it to the first patient. It’s a researcher’s dream.

Of course, no matter how beautiful the blueprint, reality is always harsh.

The authors list a pile of challenges, like how to handle “out-of-distribution” predictions (new situations the model hasn’t seen), how to quantify uncertainty, and how to seamlessly stitch together all this data and these models from different scales and sources. It’s like trying to build a functioning robot out of Lego bricks, modeling clay, and integrated circuits. The amount of work and the difficulty are immense.

In the short term, we can’t do without real biological data and human trials. But this paper points in a very compelling direction. It might not deliver a working “virtual human” tomorrow, but it proposes a framework of thinking—a possibility of running thousands of experiments in a virtual world before we ever dose the first real patient.

It’s a crazy and bold enough vision that I’m excited to see how it becomes a reality, step by step.

📜Title: Programmable Virtual Humans Toward Human Physiologically-Based Drug Discovery 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.19568

5. PairReg: Curing GNN “Face Blindness” to Help AI See Molecular 3D Structures

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have been popular in drug discovery for years, but they have a problem: “oversmoothing.”

It’s like taking a high-resolution photo and repeatedly applying a “smoothing” filter until you can’t even tell the nose from the eyes. For a molecule, the chemical environment and spatial position of each atom are its “facial features.” If the model smooths away these details on its own, how can you expect it to accurately predict properties?

So, researchers came up with Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (EGNNs). The idea was good: directly feed the model 3D coordinates—“equivariant information”—and hope it understands the molecule’s 3D structure. In theory, if you rotate a molecule, its predicted energy should remain unchanged, which aligns with physical intuition.

But a problem arose. When the network gets deeper, EGNNs also start to get confused. Traditional residual connections don’t really work in these models. As information passes from layer to layer, the valuable 3D coordinate data and the atoms’ own scalar features (like charge or atom type) get jumbled together, ending up as a mess. This is oversmoothing 2.0.

This paper in PLOS ONE, called PairReg, doesn’t invent a new network architecture. Instead, it pulls a new tool out of the old “regularization” toolbox.

The core idea can be understood this way: during model training, add a “penalty term.” This penalty term specifically watches the distances between pairs of atoms.

If the model, while updating node features, makes atoms that were originally far apart “closer” in feature space, or vice versa, it gets “fined.” This is like putting a tight leash on the model, forcing it to remember the basic spatial fact of “who is a neighbor and who is far away” while it learns abstract features.

Why is this important?

In drug design, many key properties, like the binding affinity between a molecule and its target, are extremely dependent on precise 3D conformation and inter-atomic interactions. If a functional group is off by a few tenths of an angstrom, it can turn an effective inhibitor into a useless piece of junk. If your AI model can’t even see the basic shape of a molecule clearly, then using it for virtual screening or molecular generation is like building a castle on sand.

Judging from the data on QM9 and rMD17, PairReg does work, especially as the number of layers increases. Its performance degrades much more slowly than other methods. This shows the approach is on the right track.

Of course, this has only been validated on relatively simple datasets.

The next step, according to the authors, is to apply it to macromolecular binding and drug generation. That will be the real test.

📜Title: PairReg: A method for enhancing the learning of molecular structure representation in equivariant graph neural networks 📜Paper: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0328501 💻Code: https://github.com/76technician/PairReg