Table of Contents

- Using nanoGPT as a benchmark for AI agent code optimization is a great idea, but the results pour cold water on the “AI self-improvement” hype: AI still has a long way to go.

- A system that handles both a paper’s “impact” and “relevance,” then uses two AIs to write you a summary. The hard days of literature reviews might be over.

- MDZip uses a neural network to achieve over 95% compression of molecular dynamics data, with a small trade-off in physical fidelity. For data archiving and sharing, it’s a bargain.

1. The nanoGPT Benchmark: Is AI any good at writing code?

If you’ve been on social media lately, you’ve probably heard of or even tried Andrej Karpathy’s nanoGPT. The project started as a simple tutorial for training a GPT. But good projects often take on a life of their own, and nanoGPT was no exception.

First, Karpathy used it to show everyone how to train a GPT from scratch. Then, he recreated it in C and CUDA, turning nanoGPT into a benchmark for new projects. Soon, experts in the community began using it as a “research sandbox” for their own improvements, cutting the training time for a GPT-2 (124M) model from the original 45 minutes down to just 3 minutes. This achievement is specific, measurable, and a result of human ingenuity.

Now, here’s the interesting part.

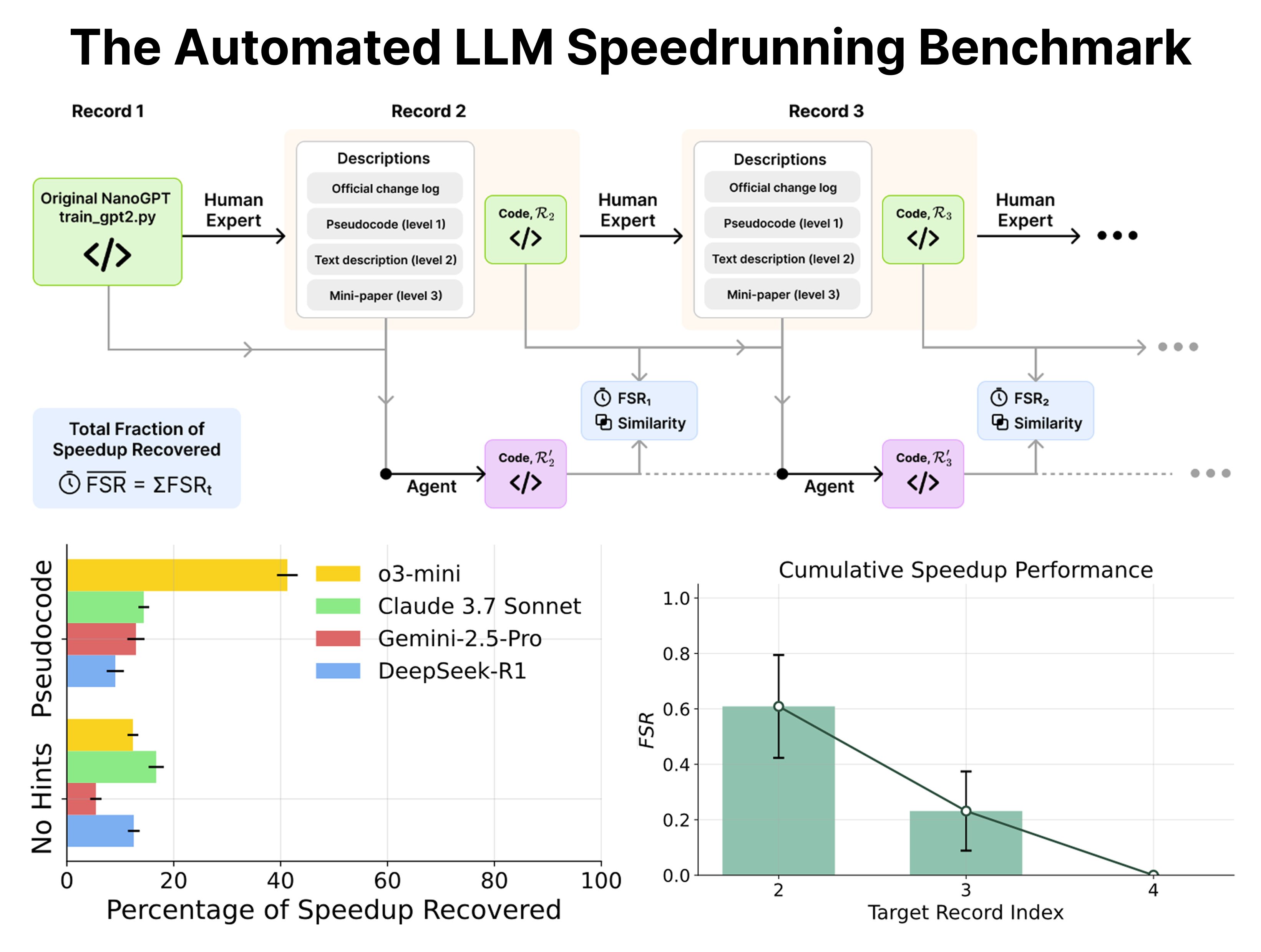

With such a clear “human record,” nanoGPT naturally became a perfect benchmark. If humans can optimize code this well, what happens if we let today’s popular LLM agents have a go? What if we give them different levels of hints and see how much they can speed up the training?

A new paper did just that. Spoiler alert: the results weren’t great.

Even with clear prompts, the AI agents’ performance was mediocre at best. It’s like telling a robot, “Improve this car’s 0-60 mph time from 10 seconds to 5,” and it just changes the tires. A human engineer would have already redesigned the engine, transmission, and aerodynamics.

This brings us to the old topic of Recursive Self-improvement. For many, the term conjures up sci-fi scenes of Skynet or “Llama 5 creating Llama 6 overnight.”

Karpathy has always had a practical view: this kind of self-improvement isn’t some “flip a switch and the singularity arrives” event. It’s already happening, but in a gradual, familiar way.

Think about it. Your IDE, code completion tools, Google Search, even Git—aren’t they all helping you build the next version of your software faster? These tools are a form of “intelligence” assisting our iteration. Now, we have a more powerful wrench in our toolbox—LLMs. We’re starting to collaborate with them on larger features, and this collaboration will only get deeper. That’s the reality.

We also have to be realistic about complexity. The entire nanoGPT project is just 750 lines of code and only covers the pre-training stage. In the real world, that’s like testing a car on a standard go-kart track. Our production codebases in the industry can have hundreds of thousands or even millions of lines. Their complexity is like trying to finish the 24 Hours of Le Mans while dealing with unexpected problems. The two are orders of magnitude apart.

Using nanoGPT as a yardstick for current AI capabilities is a good fit. It’s simple enough to let us poke at AI’s true abilities in a controlled environment. But it’s also challenging enough to expose its weaknesses in core skills like logical reasoning, planning, and code optimization.

📜Title: Can Large Language Models Automate Research? A Case Study on nanoGPT 📜Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.17387

2. A Dual-LLM Model: Your Next Research Literature Tool?

We all know the feeling of trying to find useful papers in a sea of information—it’s like trying to drink from a fire hose with a leaky spoon. Thousands of new papers come out every week. Most you’ll never read, and for the rest, just screening them and reading abstracts is enough to drain your caffeine reserves.

So when I see someone trying to seriously solve this problem with AI, I’m both hopeful and skeptical. The system in this preprint, I have to admit, has some ideas that really speak to R&D professionals.

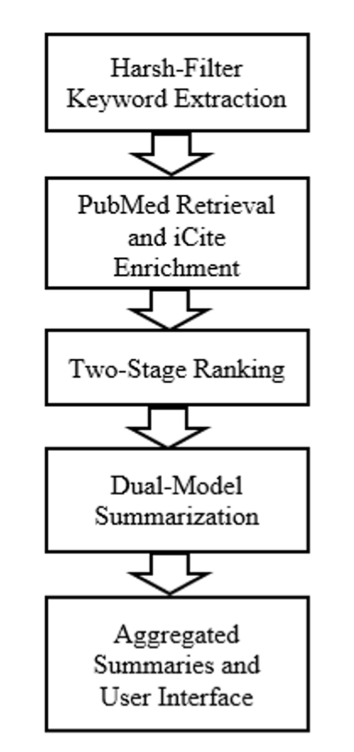

First, their ranking algorithm is interesting. We’ve all used PubMed or Google Scholar. They either give you a pile of ancient, highly-cited papers or a bunch of irrelevant new ones based on keyword matching. This system tries to find a middle ground. It combines a metric called Relative Citation Ratio (RCR) with the traditional “cosine similarity.” In simple terms, it doesn’t just care how many people cited a paper (academic impact), but also whether its content is actually relevant to your search (topical relevance). This one-two punch should, in theory, filter out papers that are “famous but irrelevant” and those that are “seemingly relevant but have no weight,” improving the quality of your results list.

The summarization part is even more interesting. They didn’t bet on a single large model. Instead, they used both Google’s Gemini 2.0 and OpenAI’s GPT-4o-mini. This is a smart move. We know no LLM is perfect right now. Some are good at grasping the big picture, while others excel at details. But they can all hallucinate with confidence. Using two models at once is like having two people independently analyze your experimental data. Cross-validating the results greatly improves the accuracy and reliability of the summaries and reduces the chance of a single model making a mistake. For people who need to quickly grasp methodologies and key conclusions from abstracts, this is a lifesaver.

Of course, talk is cheap. They ran 20 queries in the biomedical field and got an average BERT-F1 score of 0.86. That score isn’t mind-blowing, but it’s solidly in the “excellent” range, showing that the machine’s relevance judgments are pretty close to a human’s. But what I find more compelling is the feedback from 10 real users. An average score of over 4.5/5 isn’t something you can fake. Users specifically mentioned that the system’s summaries clearly highlight “research methods” and “author affiliations”—some of the most important information for people in our field. It knows what we want to see, which is much more valuable than simple text compression.

The authors also mentioned wanting to extend this approach to other fields and add “adaptive intelligence” and “privacy protection.” That sounds ambitious. Moving from biomedicine to, say, high-energy physics or organic chemistry is a huge challenge, as the knowledge graphs and terminologies are completely different. As for privacy, when you feed your research ideas as queries into a commercial company’s API, talking about privacy always feels a bit… optimistic.

📜Title: Multi-Model LLM Architectures for Personalized Summarization and Relevance Ranking in Biomedical Literature 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.29.667503v1

3. MDZip: Extreme Diet for Your Molecular Dynamics Simulation Data

Anyone who runs molecular dynamics (MD) simulations has struggled with data storage. A single simulation can easily generate trajectory files that take up several terabytes of disk space, forcing you into a constant crisis of “to delete or not to delete.” Now, someone is trying to use a neural network to put your data on a diet.

MDZip, from this paper, is the embodiment of that idea.

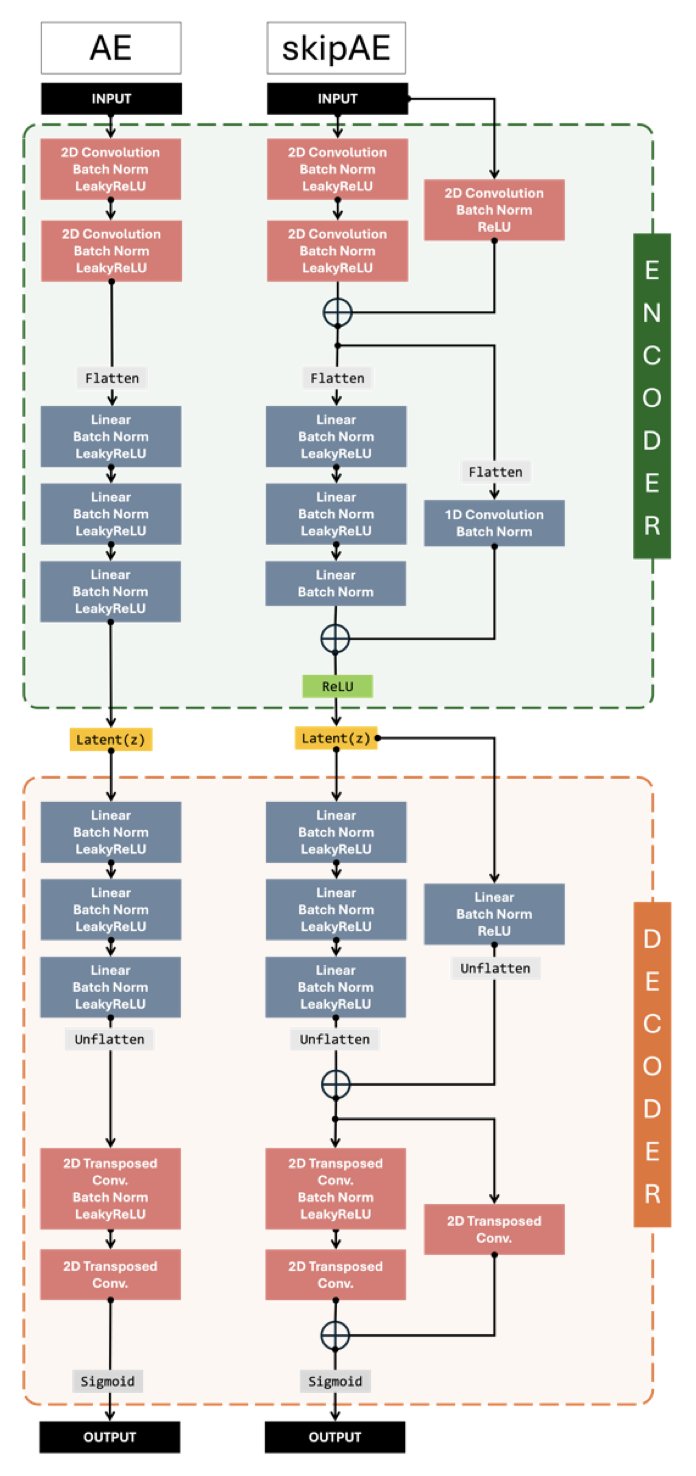

Simply put, it’s a compression framework based on a Convolutional Autoencoder. Think of it as a very smart stenographer. Instead of recording all the atomic coordinates of a protein at every moment, you train this stenographer to learn a unique shorthand for a specific system (a “compact latent representation”). When you need to review the trajectory, it can “translate” the shorthand back into full atomic coordinates.

So, how were the results?

Quite astonishing. The compression ratio is over 95%. This means data that used to require 20 hard drives can now fit on just one. For large-scale simulations and data sharing, this is a godsend.

“Sounds too good to be true. What’s the catch?”

The core of this method is that it’s a “Residual Autoencoder.” It’s a bit smarter than a traditional autoencoder. A traditional one looks at the original image (or structure) and tries to draw a copy from scratch. A residual autoencoder, on the other hand, is more like making a rough draft first and then specifically learning to correct the “differences” between the draft and the original. This “focus on correcting errors” approach allows for higher precision when reconstructing structures, with fewer strange conformations. The results show that MDZip preserves common ensemble properties like RMSF and distance distributions quite well.

But there’s a key point: MDZip is “physics-agnostic.” Its neural network doesn’t understand van der Waals forces or bond lengths and angles. It cares about one thing only: encoding coordinates in the most compact way possible and decoding them back as accurately as possible. This is both a strength and a weakness. The strength is its versatility—it works for proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes. The weakness is that the reconstructed conformations might “look good” but not be energetically reasonable. For instance, two atoms might be too close, creating a clash that shouldn’t exist.

This leads to the biggest trade-off: a loss of energy fidelity. If you plan to use the decompressed trajectories for binding free energy calculations (like MM/PBSA), you need to be careful. A conformation that is energetically unreasonable could lead to wildly inaccurate results.

The researchers were aware of this problem and offered a fix: perform a brief energy minimization on the decompressed conformations. This is like taking a wrinkled shirt out of a suitcase and steaming it. It smooths out the most obvious “wrinkles” (like atomic clashes) and brings the structure back to a more physically plausible state. But this is ultimately a patch. It can make the conformation “reasonable,” but it can’t guarantee it’s the “original” conformation from the simulation.

So, is MDZip a good thing?

It depends on how you use it. If you just want to archive massive amounts of simulation data or share trajectories with collaborators for high-level structural analysis (like seeing how a protein moves or if a loop region is flexible), then it’s a fantastic tool. It trades a little bit of energy fidelity for a whole lot of storage convenience. But if your analysis is highly sensitive to energy details, you’re better off sticking with the original trajectories.

📜Title: MDZip: Neural Compression of Molecular Dynamics Trajectories for Scalable Storage and Ensemble Reconstruction 📜Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.07.31.667955v1